Introduction

The London 2012 Olympicsi is generally regarded as the most successful Games ever. The path to success was far from smooth. One person more than any other had championed these Games for Britain for ten years, from inception to closing ceremony. Tessa Jowell, UK Secretary of State for Sport and Culture, and a senior political ally of Prime Minister Tony Blair, had overseen Britain’s successful hosting of the Commonwealth Games in 2002. With this experience, Secretary Jowell felt passionately that Britain was in a strong position to host the 2012 Olympics. She was also convinced that there could be real benefits for the country and that the Games could create a strong legacy.

The Olympics is the world’s largest sporting event on a scale far greater than any other government project. For a host city and for the government of the host country there must be gains beyond prestige. The UK government therefore planned to convert contaminated, waterlogged and derelict land in the east of London, at the heart of an effort to regenerate one of the most deprived parts of the city, into an Olympic Park with a mix of permanent and temporary venues, and accommodation for athletes and the media. London’s notoriously crowded public transport systems and roadways presented another major challenge. Overdue investment would be accelerated. Jowell was confident that with strong government support, good planning and management these challenges could be met. The far greater initial challenge was winning support across government and with the wider public.

This case explores what lay behind the success of the London Olympics. How the lessons from the Games can be applied to ministerial leadership in implementing other ambitious government priorities and projects. This case is based mainly on in-person interviews with Tessa Jowell, as well as reported interviews by other principal players in the delivery of the Games.

Building Political Support

The UK had a track record of failure in Olympic bidding. The UK put Birmingham up for the 1992 Games and Manchester for both the 1996 and 2000 Games. The bid from Birmingham and the first Manchester bid ended in embarrassment, with both coming fifth out of six competing cities. By contrast, the Manchester bid for the 2000 Games saw the city achieve a more respectable third place.ii By 2002 the International Olympic Committee (IOC) was clear that only a bid for the Games in London would be seriously considered.

The newly appointed Secretary for Sport and Culture, a seasoned politician, was impressed by the successful delivery of the Commonwealth Games and understood the “co-lateral benefits” of such major sporting events. Jowell, a progressive member of the British Labor Party, saw real potential gains for the British economy, boosting employment and regenerating a seriously deprived section of east London. She was supported in this latter objective by the Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone — known by many as “Red Ken” referring to his leftist political leaning. The Mayor saw the Games as a way of securing cash to regenerate London’s East End — an important part of his political agenda.

Prime Minister Tony Blair was a “sports nut,” but the Prime Minister was not in the early stages prepared to wage the political battle to get government and public support. Getting his support was critical. Blair told Tessa this was up to her. The Prime Minister was particularly wary of picking this battle with Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown. Tension between the Prime Minister and Chancellor are well documented.

According to Jowell, there was little initial support in the government or the civil service for hosting the Games, and the strident criticism of the media created deep public skepticism. Jowell knew that she had to proceed strategically. She says that taking the time to persuade key players individually was essential to selling the idea. This ensured they would not feel steamrolled. If the UK was to bid for the Games the Cabinet had to own the ambition too. Over more than six months, she met individually with senior government colleagues and strategically laid out the potential benefits to each of their departmental and political priorities. Jowell’s pitch was built around the answers to four questions:

- Was the project deliverable?

- Was it affordable?

- Would it leave a legacy?

- Could we win and beat Paris?

The substance of Jowell’s pitch was that the Games would be a major shot in the arm for the UK economy with substantial additional benefits in areas such as transportation, tourism, infrastructure development and urban regeneration, as well as boosting sport, physical wellness and national spirit. The IOC would be impressed by the evidence of ambitious planned legacy. Jowell knew that it was also important to her credibility not to overplay expectations; she needed to ensure projections of the probable benefits were not mere hyperbole, but based on solid evidence. She also had to be sure that the eventual budget was sufficient and that the project could be delivered “on budget and on time.”

Jowell left the biggest challenge until the last before seeking formal Cabinet approval. The Treasury had made clear its opposition to the idea and the Chancellor avoided engagement, declining for weeks to meet with Jowell. His support was essential to persuade the rest of the Cabinet. Jowell says she deployed a combination of “persistence, charm and a flash of steel” in eventually forcing a meeting with Chancellor Brown days before the Cabinet was scheduled to consider whether or not to agree on support for the proposal to bid for the Games. The Chancellor was eventually engaged in the face of Jowell’s persistence. She at that stage knew that she already had the support of the Prime Minister and most of the Cabinet.

In May 2003 the Cabinet gave the go ahead for the bid and London became a late entry in the race to host the 2012 Olympics – with Paris still very much the lead contender. Over the next two years the bid company was established and the underpinning machinery of government was put in place to maximize success and to safeguard the necessary financial guarantees from government departments (and the opposition) to allow the London bid to proceed.

The Game is On: Marshaling Resources

Jowell, with the support of London Mayor Livingstone, set about addressing some of the most significant hurdles to a bid, namely the cost, and concerns that London had no chance of beating a better-prepared Paris. They needed more information about the likely necessary budget and jointly commissioned a consulting company, Arup, to undertake a cost-benefit analysis of a specimen Olympics. Initially, Arup reported that the Olympics would need a public subsidy of £1.1bn.iii However, by Christmas, the press was reporting that the Olympics could cost the taxpayer as much as £2.95bn. The Olympic budget caused headaches from the start. There were so many uncertainties and unanswerable questions. There could be no site surveys to assess the scale of essential remediation. The Delivery Authority which would build the Park might be liable for VAT, but that could not be settled until the technical details of its functions were clarified. At that stage, consultant advice was that project contingency would be sufficient. This was much less than the programme contingency of 60% subsequently required by the Treasury.

Jowell prepared the groundwork for public funding, agreeing with Ken Livingstone that up to £1.1bn of public subsidy would be met by London, split equally between the London Development Agency (LDA) and London council taxpayers.iv Thanks to Tony Blair’s predecessor, John Major, there was an additional source of funds potentially available which would not place a burden on the taxpayer – the National Lottery that had opened for business in 1994. Jowell also met with lottery operator, Camelot, and the Lottery Commission to discuss raising £1.4bn through an additional Olympics Lottery game. This was controversial since the decision to divert Lottery Funding of 11% from all specialist distributors plus the creation of an Olympic Lottery Fund meant less for non-Olympic programmes. This received an angry reaction from many quarters.

The task of convincing colleagues and the public that a win was possible was more difficult. Formal government decision-making about the bid process was through “Misc 12” – a cabinet committee chaired by Foreign Secretary, Jack Straw. It remained wary as the common view persisted that Paris would host the 2012 Games. Such was the concern over Paris being the pre-ordained victor of the bidding process that Jowell decided to go to Switzerland in January 2003 to seek assurances from IOC chair Jacques Rogge about whether “this [was] actually an open race or a competition that [would] lead to a Paris victory.”v He gave absolute assurance about the openness of the contest. This was important. The timing of a government decision to proceed with the bid was further complicated by the imminent military intervention in Iraq. A government decision on the Olympics was originally due in February 2003 but was delayed by three months while the potential war with Iraq obviously took main priority.

Some have argued that ironically the presumed “unwinnability” of the Games was helpful to those pressing for a London bid. After all, some reasoned when signing up, there was little risk they would have to deliver – Paris was going to win, and it was not worth antagonizing cabinet colleagues and wasting political capital opposing something that was highly unlikely to happen.

Organizing a Winning Bid

With the clock ticking down on the deadline for submission of the 2012 bids, Jowell now had to combine her role as chief political champion with that of top executive, assuming responsibility as the newly appointed Minister for the Olympics responsible for winning the bid and delivering the Games. She knew from experience that her leadership would only be as good as the team around her.

A team to lead the bid was assembled, and in line with IOC rules, a private bid company named London 2012 took charge of this. Barbara Cassani, an American businesswoman who had successfully launched British Airways’ low-cost airline, Go, was appointed by Jowell after open competition to chair London 2012. Keith Mills, described by Barbara Cassani as “one of the least known, most successful businessmen in Britain,” became Chief Executive. Between them, Cassani and Mills had just over a year to create a master plan (known as the ‘Bid Book’) that would:

- Detail where events would be held and what infrastructure would be built

- Provide an overall budget projection for the staging of the Games

- Persuade the public to support the Games through a significant marketing campaign

They also had to organize a huge lobbying effort to convince the 115 IOC members, the electorate for the Host City 2012, that London was the right choice. Jowell recruited Sebastian Coe to lead on liaison with the IOC. Sebastian Coe, a celebrated Olympic gold medalist and a former Conservative Party member of the British parliament, was a strong addition to the team.

London 2012 was given the freedom to lead on developing the Bid Book. The company board and a monthly crosscutting committee chaired by Mills were the main interfaces with Government. It was here that London 2012 met with Government to agree on the crucial departmental guarantees that were to be signed by relevant secretaries of state, which the IOC required of all candidate cities. London 2012 was directly accountable to Tessa Jowell. Importantly, Jowell notes, there was no back channel to the Prime Minister. Jowell had been clear from the beginning that there could be no confused lines of accountability.

In May 2004, London passed the first hurdle when the IOC selected it as one of the five formal candidate cities – along with Paris, Madrid, New York, and Moscow. This triggered a change of leadership at London 2012. Barbara Cassani decided she was not suited to the next stage of the lobbying task. She suggested to Jowell that Seb Coe, as a double Olympian, would be the most powerful Bid leader. Jowell then negotiated his appointment in the face of some politically tribal skepticism. London was now moving into the final stages of the bid, finalizing details of the candidate file to be submitted in November 2004.

At this point, Coe, Mills, and other London 2012 staff stepped up their work with politicians on speeches and marketing materials that would showcase London. Politicians – most often Tony Blair, Ken Livingstone, or Tessa Jowell – were asked to give speeches according to which of them IOC members would be most impressed by. In some cases, a mayor was the most appropriate figure, while in others a prime minister or Olympics minister was a better fit. The key to these events was encouraging the individual politicians to set aside their specific objectives (e.g., the regeneration of East London) to emphasize the importance of a great and successful Games. This was by far and away the most important test for the IOC.

Even then, the UK was still perceived as the underdog. In January 2005, The Guardian newspaper reported that the bid team was demoralized at being “so far behind Paris.” Even bid company staff acknowledged that “the consensus was that we weren’t going to win anyway.”

The bid company spearheaded an impressive marketing campaign and Olympics offer. Despite this, the majority view in the UK remained that the UK would not win. In the final months leading up to the IOC decision, Jowell and the bid company worked tirelessly to increase public support for the Games and developed an even stronger marketing program. In its final lobbying activities, three key points were emphasized by those representing the UK:

- The sports experts highlighted the technical merits of the stadium design, which was seen as more sophisticated than Paris’ Stade de France.

- Tessa Jowell pledged support from government investment for elite sport and a legacy of investment in school sport and adult participation in sport and physical activity.

- Ken Livingstone praised the transformative potential of the Games for London.

All this was sealed with a bit of glamour, with appearances from British Olympics Association chair, Princess Anne, and legendary soccer star David Beckham in the final publicity blitz, with Prime Minister Blair on hand to “press the flesh” of IOC officials in the final hours before the bid-deciding IOC meeting. To cap this, Jowell and Coe agreed that they had to “go for broke” in the presentation to the IOC. “Safe” would deliver the Games to Paris. They therefore decided to showcase, not the corporate sponsors, but 20 young people from East London. They were of more than 10 nationalities speaking 20 languages. Theirs were the faces of modern London.

While the technical plans and marketing campaign might not have convinced the home crowd (or the bookies; the odds were still on Paris the night before the decision was announced), it convinced the people that mattered. The risks paid off, and against all expectations, on 6 July 2005, London was announced as the host of the 2012 Olympics.

The British public were euphoric, and even the institutionally cynical British media had to put a positive spin on the come-from-behind win. Jowell, exhausted by the effort, woke up the next morning saying she “felt the awesome loneliness of leadership.” Weighed down by the huge responsibility that lay ahead even after such a marathon struggle to win the bid, she says the thought crossed her mind that “second place might not have been so bad.” That lasted a moment before her focus shifted to “now we have really got to do it.”

A False Start

Before the Olympics Minister could get home to London, the euphoria turned to catastrophe when four suicide bombers exploded bombs on the London transport system, killing 52 people. All the attention and resources of government were diverted in response to the worst terrorist attack ever on the British mainland. Jowell was given responsibility for government support for the affected families and survivors. This was totally consuming for many weeks after.

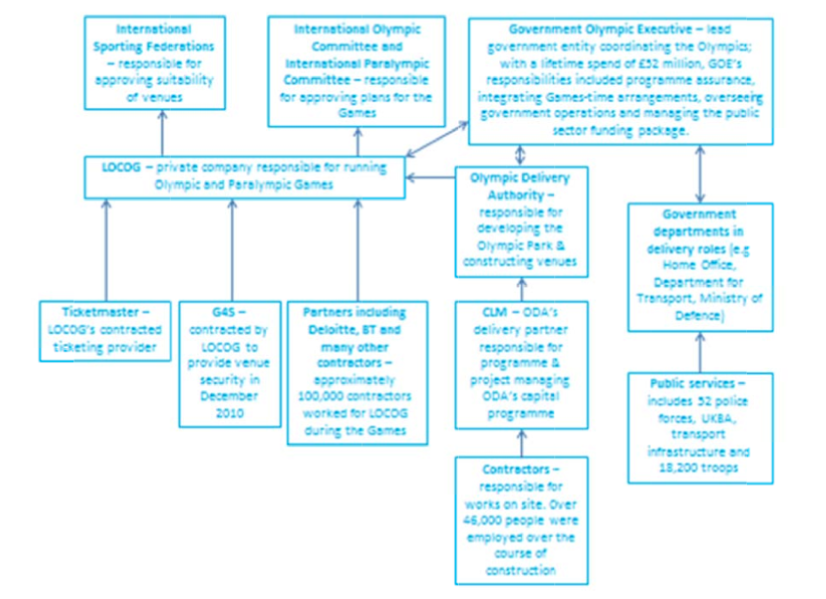

To move from bid to staging the biggest ever event in the UK required the establishment of new delivery bodies:

- The Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA) as a public body to build the venues;

- The London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (LOCOG) as an independent entity to fund and stage the Games. (See Appendix A for an overview of the Olympic delivery bodies.)

Government also had to establish trading rules in the vicinity of the Games, establish advertising restrictions which would later become the subject of controversy, and ensure the land needed for the Olympic Park was under public control. The London Development Agency (LDA) had started purchasing the site of the Olympic Park earlier in 2003. Work on the Olympic Park started in the summer of 2004, after the existing occupants – including allotment owners, businesses, travelers, and feral cats – were evicted from the site.

Due to the significant pre-planning about governance and legislative plans in the event of a successful UK bid (structures, organizations, and shareholders agreements had all been signed off at the insistence of the bid company to avoid post-bid delays), the London Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Bill was introduced in Parliament just over a week after the announcement that London would host the Games. This speed was a real achievement and radiated confidence.

But while land purchasing, undergrounding power lines, and Games legislation – including the design of and appointments to the Olympic delivery institutions – were well planned and quickly executed, government was less prepared when it came to its own role in the Games. There were disputes about which department would lead on the Games, what civil service capacity existed for a major delivery project, and, crucially, the real size of the budget.

Before the bid was won, Jowell had made clear that, if they won, the budget would have to be reviewed. By the end of 2005, Jowell knew that the actual cost of delivering the Games was going to be substantially higher than the £2.9 billion publicly bandied about before the bid and the final bid number of £4.2 billion. The main reason was that once thorough site inspections were completed and detailed plans developed, it was possible for the first time to calculate the real cost. Security requirements had to be ramped up following the bombing attacks. Throwing fuel on the fire, the Treasury insisted on adding a 60% contingency on the whole project and required the ODA to pay VAT, adding a further £1 billion to the bottom line and pushing the total to £9.2 billion. It took nearly two years to settle the revised budget. According to Jowell, Prime Minister Blair was furious about the Treasury’s deliberate attempt to sabotage the Games. (See Appendix B for a budget timeline.)

The Prime Minister initially refused to accept the new budget number, but eventually told Jowell “to use her own judgment” and left it to her to present and justify the revised budget to the UK parliament. Compounding what Jowell calls a “real moment of crisis,” the media had a field day, panning Jowell’s leadership and the credibility of the effort.

The Treasury initially demanded that it should have sign-off on contracts exceeding £12 million. Jowell says that the Treasury contended it was worried about cost control, but in reality, they were “agents of delay,” aggressively questioning every contract. In a final showdown with the Treasury Committee assigned oversight of the Games, Jowell challenged Committee members to say which of them had ever built a stadium or managed a major sporting event. Of course, none had. Her point well made, Jowell told the Committee she had hired the best people for the job and they should be allowed to get on with their work. She was able to support her stand by showing that up to that point all implementation targets had been met on time and under budget. This included most impressively the undergrounding of the power cables which crossed the site of the Olympic Park.

Government itself had to gear up to oversee what the ODA and LOCOG were doing. The Olympic Park Development was the largest public sector construction project in Europe but compounded by the risk of a fixed deadline for completion.

It did this by creating the Government Olympic Executive (GOE), which Jowell chaired. GOE was purposely designed as a stand-alone unit. As Olympics Minister, Jowell was a passionate advocate, supporter, and broker for the Olympics within government and outside it.

Jowell had hardly secured these victories when Olympic super-skeptic Chancellor Gordon Brown succeeded in his long-time ambition to unseat Prime Minister Blair. Fortunately for Jowell, most of the major agreements were locked in place and implementation was well underway. Brown did not replace Jowell as Olympics Minister, which as incoming Prime Minister had been his prerogative.

The Final Sprint

With stadium construction finally underway in 2008, Jowell was dealt another double blow. Close political ally London Mayor, Ken Livingstone, lost his re-election bid to Conservative Party candidate Boris Johnson. But worse still was the 2008 financial crisis, which saw global stock markets tumble and governments in Europe and the U.S. facing financial catastrophe.

The election of Boris Johnson altered little, mainly because plans were far advanced and London was a major beneficiary. In contrast to the ease of the mayoral transition, the 2008 financial crisis created significant challenges for the project. While most of LOCOG’s sponsorship revenue had been raised prior to the economic downturn,vi the collapse of the private funding of the Olympic Village was seen as the largest budgetary crisis. In May 2009, government made a decision to ramp up the public sector contribution by £350m.vii This proved a sound investment as the Government’s share of the Village was later sold for £570 million.

In the midst of the financial storm and hardly two years before the Games, Jowell’s Labor Party lost the general election to a Conservative-Liberal Party Coalition. Jowell was no longer Olympics Minister. However, Jowell’s foresight in establishing cross-party management of the Games was vital to the stability of the project at this critical stage. The new Minister, with whom Jowell had established an extremely good relationship, had shadowed the Olympics brief since 2004 and throughout this period had unusual access to government briefings on the progress of the Olympics project. He felt “it was a great help to have shadowed the brief for five years” because this, and regular briefings, allowed him to hit the ground running. Jowell says because she had worked hard to build cross-party support, and because the implementation process had been disciplined, turning in projects on time and mostly on budget, the government had little quarrel to pick with what was likely to be a big boost for the national morale at a very difficult economic time.

The new government immediately launched a period of harsh financial austerity to get control of Britain’s extraordinary public debt. While the Olympic budget came under scrutiny, the new Sports Minister recalls that “given the importance of the project, the Olympic budget was largely protected.” Ultimately, only £27 million was taken out of the £9.3 billion funding package for the Olympics, with a totemic decision to remove the publicly funded wrap around the stadium.viii This was subsequently and controversially replaced by a privately tendered wrap, manufactured by Dow Chemicals.

By early 2011, public awareness of and interest in the Olympics started to increase. The public ticket ballot opened in spring 2011 to a flood of interest with 1.9 million people applying for tickets, although many were left disappointed and dissatisfied as they failed to get the tickets they applied for. Jowell’s early insistence that the tickets should be available by ballot and not only with the rich and famous at the top of the queue over time dulled some criticism, but ultimately the ticket applications reached some 24 million, far outstripping availability.

Olympic stadium construction was completed in March 2011, on schedule and over a year ahead of the Games. This was a triumph for ODA, government, and the delivery partner CLM who had met their target date with relative ease.

Now with a year to go, the baton was passed onto LOCOG, thousands of volunteer Games Makers, and operational partners including Transport for London (TfL), the police, the Borders Agency, and the military, who needed to test and prepare the country for Olympics action. The Foreign Office, Defra, and Cabinet Office all had roles to play too – from using the run-up to the Olympics for diplomatic opportunities to ensuring vets were on hand for animals used in the opening ceremony. (See Appendix C for the scale of public sector activities.)

A series of Home Office-led test exercises with police, military, and emergency workers took place to ensure security and other operational concerns were ready for the Games and that “everyone was in the right frame of mind.”ix These exercises included “Exercise Forward Defensive” – a February 2012 two-day exercise involving 2,500 people simulating a response to a bomb on the Tube networkx and “Exercise Olympic Guardian,” which took place over eight days in May 2012 and included the deployment of fighter jets, helicopters, and ships around London and Weymouth.xi The final test exercises neatly transitioned into the operational phase of the Games, which officially began on 19 May 2012 when the Olympic Torch Relay began.

As the Games approached, TfL, the Department for Transport (DfT), and LOCOG were working to prepare Londoners and their transport system for the estimated 20 million extra journeys that would take place during the Games. The major public information campaign encouraging individuals to plan their travel during the Games started on 30 January 2012.xii Prior to this, organizations involved in delivering public transport during the Games had started working with businesses in November 2010 through the “Travel Demand Management Business Influencer Campaign,” urging businesses to plan for the impact of the Games. The Department for Transport led a cross-government initiative to reduce travel into central London with 17 government departments committing to change at least 50% of their own travel footprint over summer 2012. A trial week for this programme called “Operation Step Change” took place in spring 2012. Testing of the Olympic travel programme continued into July 2012, with commuters being deterred from central London through delays caused by the testing.xiii Overall this was a successful programme, with up to 35% of people adapting their normal travel behaviour to take account of the Olympics.

The role of LOCOG during this period should not be underestimated. They took control of the Olympic Park in January 2012, at which point large quantities of work in order to make venues Games-ready still needed to be undertaken. They received considerable assistance from the ODA with this. In addition to the work on venue preparation, they organised the Torch Relay, which confounded expectations and was viewed by an estimated 12 million people as it made its journey around the UK.xv LOCOG also had key roles to play in areas including venue security, transport management, and the monumental task of training and working with thousands of volunteer Games Makers, another runaway Games success story. Although TfL were responsible for running London’s public transport system, LOCOG’s role included assisting with the development of the Olympic Route Network and working with transport partners on delivering the public transport system. Similarly, although the Home Office was ultimately responsible for delivering security arrangements around the Olympic Games, LOCOG were responsible for contracting for security arrangements at the Olympic venues and playing an increasingly leading role in discussions around security in the run-up to the Olympics.

Overall this went remarkably smooth, with the very serious exception of G4S failing to fulfill their contract to deliver a full complement of guards for venue security. This was a major hiccup in the last weeks before the Games and was subject to intense media scrutiny. In the event, the detailed contingency planning that government had undertaken in collaboration with LOCOG moved into action quickly though, and the armed forces were deployed to fill a 3,500-person shortfall. This was not the disaster it could have been, as a senior civil servant at Cabinet Office recounted: “the plan was exactly as it was, just with more highly trained and disciplined personnel providing the security.”

As the end of July drew close, eyes now turned to the Olympics themselves. The torch relay had built a mounting enthusiasm for the Games and only weeks before the Opening Ceremony, UK Sport confirmed they were aiming for Team GB to finish in the top four of the medals table with a medal take of at least 48 medals.

Finally the Flame is Lit

A decade after Jowell embraced the idea that London should host the 2012 Olympics, she watched the Olympic torch lit in the spectacular main Olympic arena. What followed were the most successful Games in Olympic history. Jowell, through determined and unrelenting leadership, had succeeded against enormous political, economic, and organizational odds. In retrospect, Jowell says she thinks success at the end of the day was because the effort reflected the “values and the mood of the time.”

Jowell says the project had been very sensitive to local communities affected by the Olympics infrastructure development, they kept costs under control, and the entire process had been transparently conducted. Jowell also takes pride in the fact that not a single life was lost nor any serious injury occurred in the construction of the Olympic venues.

Despite initial reticence, the British public enthusiastically embraced the project because many communities beyond the city of London had seen benefits from the build-up to the Games, but also because the nation desperately needed a morale boost as it wrestled with the worst economic crisis in a century. In retrospect, Jowell says that the most troubling part of the process was the time it took to come up with a reliable cost estimate. The Olympic bid process makes this almost impossible and the eventual budget contained large provisions, VAT, a doubled security budget post-London bombings, and a programme contingency of 60% that could not have been foreseen three years before the decision to award the Games to London. Sometimes, as a leader, you just have to be prepared to take the beating!

Questions for Discussion

- How did Jowell continue to focus on her priorities in spite of the recurring distractions?

- How did Jowell manage the politics, including the relationship with the PM and the Chancellor of the Exchequer?

- How did Jowell ensure continuity of her goal through a change of government?

- How did Jowell secure the right financial support to deliver on her mission?

- What did Jowell do to build a strong and effective team?

Appendix

Appendix A: The Olympic Delivery Bodies

LOCOG and the ODA both sat outside of government, but were hugely different organizations. The ODA – as a statutory executive NDPB – existed in a structure with which DCMS was familiar. The London Olympic and Paralympic Games Act 2006 gave the ODA broad powers, including the right to “take any action that it thinks necessary or expedient for the purpose of preparing for the London Olympics.” The Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport had responsibility for appointing the ODA Board, the first ODA chief executive, and had the right of veto over appointees to be finance director, transport director, or any chief executive other than the initial appointee.

LOCOG was an entirely different entity. Its structure had been agreed during the bid phase, meeting the requirement of the Olympic Charter that it report directly to the IOC Executive Board. It was clear from interviews that while LOCOG viewed its relationship with government as important, its crucial relationship was with the IOC. LOCOG was accountable to its three stakeholders – the Secretary of State, the Mayor of London, and the British Olympic Association – who were collectively responsible for appointing the Board under the terms of a joint venture agreement. As a private company limited by guarantee, however, it did not see itself as having a conventional “sponsorship” relationship with government. This was heightened by its determination to remain financially independent of government, raising its £2bn budget from the private sector and IOC (while government would put close to £1bn into LOCOG, this was largely to cover scope transferred to LOCOG, rather than for its core functions).

Appendix B: The Budget Timeline – Key Events

- May 2003: Government and Mayor of London agree memorandum of understanding providing a public sector funding package (PSFP) of £2.375bn to meet the costs of the Games – £1.5bn of which would come from the National Lottery. Government also commits a further £1.044bn of Exchequer funding for non-Olympic infrastructure. Combined with anticipated private sector funding of £738m, the expected gross cost of the Games was £4.036bn (excluding the LOCOG budget).

- 31 October 2005: Olympic cost review steering group (an officer-level group initiated to review all costs associated with the London Olympic Games) meets for the first time.

- 21 November 2006: Tessa Jowell indicates to the House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee that additions to the Olympic budget in the bid will include an additional £400m to be spent on the ODA’s delivery partner, and £900m in the costs of the Olympic Park. Further liabilities are identified as the tax status of the ODA, the need to develop a programme contingency, and increased security costs.

- 15 March 2007: Revised PSFP announced, including ODA budget of £5.254bn, an ODA tax bill of £836m, a £2.247bn programme contingency and revised policing and wider security costs of £600m, up from £190m at the time of the bid.

- November 2007: Announcement of ODA baseline budget at £6.09bn, which served as a basis for future reporting.

- 13 May 2009: Public sector funding is agreed for the construction of the Olympic Village after a potential public-private deal collapses.

- 24 May 2010: PSFP is reduced to £9.298bn.

- 20 October 2010: PSFP is not reduced in the Comprehensive Spending Review; the publicly funded “wrap” around the stadium is removed, saving £7m from within the PSFP.xvi Dow Chemical won a competitive tendering process to privately fund a wrap around the stadium in August 2011. PSFP funding is shifted from construction to operations.

- 12 August 2011: Majority of the Olympic Village and adjoining land is sold to Qatar’s investment arm for £557m.

- 6 December 2011: DCMS and National Audit Office both report that venue security costs have risen to £553m – an increase of £271m from October 2010. The NAO also puts the cost of 18 legacy programmes at £826m, with this cost sitting outside the PSFP for the Games. £41m of public money is put into LOCOG to fund more ambitious opening and closing ceremonies for the Olympics and Paralympics, with a total of £354m of uncommitted programme contingency remaining.

- 31 October 2012: Final GOE quarterly financial update is released. The anticipated final spend against the PSFP is £8.921bn – a £377m saving. Estimated costs of policing and venue security respectively are £455m and £514m – a combined decrease of £60m against expectations in May 2012.

- 14 November 2012: LOCOG release details of their revenue streams to the Greater London Assembly, showing that their upper sponsorship target of £700m has been exceeded by £46m.

Appendix C: Public Sector Scale

- 11 hospitals designed as “Olympic hospitals” on standby to provide free medical care for the “Olympic Family”.xvii

- 52 police forces involved in providing security for the Olympics – every police force in the country.

- 98% of scheduled kilometres run on schedule on the Tube, London Overground, and London bus network during the Olympics.

- 200 extra buses provided in London for the Games.

- 4,000 extra Games-time train services provided over the Olympics and Paralympics.xviii

- 13,000 London businesses attended seminars prior to the Olympics where TfL explained Games transport impacts.

- 15,000 police officers deployed on the Olympic operation on peak days.xix

- 18,200 troops required to provide security for the Olympics at peak timesxx – nearly double the number serving in Afghanistan at the time.xxi This number consisted of 13,500 service personnel announced in December 2011, a further 3,500 deployed as assurance against G4S’ failure to meet their contract on July 12, 2012,xxii and an additional contingency of 1,200 troops called up on July 24.xxiii

- 138,000 passengers handled by Heathrow on the busiest days of the Olympics – up 45% on normal levels.xxiv

- 450,000 people requiring some level of special access for the Games who were background-checked by the UK Border Agency (UKBA), including contractors, “Olympic Family” members, and volunteers.xxv

- 3,000,000 additional public transport trips above normal levels on the busiest day of the Games in London.xxvi

References

Where relevant throughout this report references to the success of the ‘Olympics’ should be taken as applying to the success of the 2012 Olympic & Paralympic Games.

- House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee, A London Olympic Bid for 2012 (2003), p. 11

- House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee, A London Olympic Bid for 2012 (2003), p. 16

- Mihir Bose, “Olympics: Jowell seeking to win over skeptics,” The Telegraph, January 29, 2013, link

- Mike Lee, The Race for the 2012 Olympics (2006), p.14

- Roger Blitz, “Rogge hits back over sponsorship criticism,” Financial Time, July 9, 2012, link

- Owen Gibson, “Olympic Village to be fully funded by taxpayers,” The Guardian, May 13, 2009, link

- ODA, 2011/12 Annual Report

- “London 2012: Olympics and Paralympics security test,” BBC News, February 22, 2012, link

- “London 2012: Major Olympic security test unveiled,” BBC News, April 30, 2012, link

- House of Commons Transportation Committee, Section 3.5 from Session 2010-12 on Transport and the Olympics, March 14, 2012, link

- Sam Jones, Paul Owen, and Haroon Siddique, “Olympic test-run on London transport leaves commuters grumbling,” The Guardian, July 10, 2012, link

- Simon Israel, “New security challenges for Paralympic torch relay,” Channel 4 News, August 20, 2012, link

- “Scrapping London 2012 curtain ‘sensible’, Lord Coe says,” BBC News, November 2, 2010, link

- London 2012 Olympic Games healthcare guide

- Network Rail, Our Plans for London 2012

- House of Commons Home Affairs Committee, Olympics Security (2012)

- David Horsey, “U.K. military at Olympics outnumber U.K. troops in Afghanistan,” Los Angeles Times, July 27, 2012, link

- Hansard HC Deb 12 July 2012, vol 548, col 451

- House of Commons Home Affairs Committee, Olympics Security [OS 07] (2012)

- Heathrow Airport, Heathrow’s Preparations for the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games

- UKBA 2011/12 Annual Report

- TfL, Hosting a Great Games and Keeping London Moving this Summer