Executive Summary

High-quality delivery systems are effective at achieving outcomes, efficient at utilizing resources, equitable at providing services, and resilient in the face of challenges.

A high-quality health system should support the physical, mental, and social wellbeing of the people it serves and a high-quality education system should help students reach their full potential as productive members of society. The likelihood of achieving improvements in the health, education, and economic development of a population hinges on the quality of the underlying and interrelated health and education delivery systems.

This policy brief provides an overview of three key areas in health and education: human resource motivation and performance; procurement, supply delivery and management; and data for decision-making. It reviews challenges and potential policy options to guide quality improvement efforts in those areas. A summary table is included in Annex 1.

Human resource motivation and performance are fundamental to equitable service provision and effective achievement of health and education outcomes. Key challenges include absenteeism; professional attrition (either to urban areas or high-income countries); and low technical competence. Root causes of these challenges include inadequate professional training; stressful working conditions; scarcity of essential supplies and materials; heavy and increasing workloads; low and unreliable remuneration; and lack of opportunities for growth and professional development.

Policy options to tackle these challenges could include reforming remuneration schemes to create a stronger link between payment and performance indicators. Changes could also be made to the recruitment and deployment strategies for health and education workforces, including setting higher admissions standards into the profession, diversifying the workforce and putting in place measures to attract and retain staff in underserved areas. Policies could also include enhanced professional development programs, either in-service or using technology to facilitate remote learning and supervision. Finally, technology could also be integrated into monitoring and service delivery systems to make them more accountable and responsive.

Procurement, supply delivery, and management systems critically affect efficient resource utilization and effective achievement of health and education outcomes. In education, the provision of textbooks is a challenging area for supply chain and procurement, but one which yields excellent returns on investment. Across both the health and education sectors, weaknesses in national procurement and supply chain systems are leading to stockouts and waste of essential supplies, inflated prices, and poor quality of products (including counterfeit or ineffective medicines). The causes of these issues range from high production and import costs, difficulties with making accurate forecasting and requisition estimates, inadequate storage and transportation conditions (which can lead to theft or damage), as well as diffused responsibility in the underlying accountability structure and unpredictable financing.

Effective policies to strengthen these systems should be carefully adapted to the local context and capacity but could include seeking procurement agreements with national or regional producers, the private sector, or through a pooled funding arrangement. Policies could also aim to centralize procurement or streamline the distribution of essential goods, while also potentially reducing the number of wholesalers and intermediaries to drive down costs. Distribution processes could be improved through investments in strengthening the stock-management and requisition systems at local levels (potentially enabled by technology), shortening the lag between replenishment cycles, and integrating systems for improved product traceability and efficient transportation. Finally, focusing on developing and retaining a qualified procurement and supply chain workforce is an important area to consider.

Data-driven decision making is a fundamental delivery tool that impacts the equity, efficiency, resilience, and effectiveness of a delivery system. The availability of quality data is often inadequate in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) as well as underutilized when available. Data from health and education systems are often managed in a fragmented system with little capacity for rapid and digestible analysis and dissemination. At the root of this situation is a history of underfunding national statistics offices, an over-emphasis on donor-driven aggregated surveys for cross-national comparisons over disaggregated and actionable national-level data, as well as weak demand for data from users (from government decision makers to citizens).

To enact the “data revolution” called for by the UN, initiatives should be put into place to improve the quality of data, through financing more robust national statistical offices, performing enhanced data audits and better aligning donor and local data streams. The key indicators for each sector should be chosen to reflect the desired outcomes (quality) and not just quantity and should include regularly administered internationally recognized standard measures. Policies should also be enacted to create a culture of “demand for data” at every level, as well as working with data producers to create user-friendly products that meet the needs and are easily actionable for decision makers.

Introduction

There has been increased attention in recent years on moving beyond accessing services to focusing on the quality of service delivery across health and education. High-quality delivery systems are effective at achieving outcomes, efficient at utilizing resources, equitable at providing services, and resilient in the face of challenges. Thus, a high-quality health system should support physical, mental, and social wellbeing of the people it serves and a high-quality education system should help students reach their full potential as productive members of society. The likelihood of achieving improvements in the health, education, and economic development of a population hinges on the quality of the underlying and interrelated health and education delivery systems.

Strategies to improve quality must include policies to improve resource utilization and service delivery in three key areas: human resource motivation and performance; procurement, supply delivery and management; and data for decision-making. This brief will seek to provide context, as well as possible policy options and combinations, to guide quality improvement efforts.

Quality in health systems

A recent Lancet Global Health Commission on High Quality Health Systems in the SDG Era1 has called for “a revolution” in health care quality. Despite gains in health outcomes globally, the commission points to the often poor quality of care provided across LMIC, which leads to nearly eight million avoidable deaths each year. As countries strive to provide universal health coverage (UHC), an integral part of achieving SDG 3 “Good health and well-being,”2 they must also make improving quality a core component of these efforts, together with expanded coverage and financial protection. The Commission’s report includes among the foundational elements of high-quality health systems: workforce numbers and skills, tools and resources from drugs to data, as well as the capacity to analyze and learn from data.1

Quality in education

Since 2000, there has been enormous progress around the world toward achieving Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 2: universal primary education. Total enrollment rates reached 91% in 2015 in developing regions, and the number of children out of school was halved.3 However, these efforts have often eclipsed concerns around the quality of education, a concept which encompasses the learners’ cognitive development and the “promotion of values and attitudes of responsible citizenship and in nurturing creative and emotional development.”4 The 2018 World Development Report has called the current situation a “learning crisis,” with hundreds of millions of children worldwide failing to learn basic arithmetic and reading skills. To address this, SDG 4 is concerned explicitly with “quality education.”

Within UNESCO’s framework for understanding education quality,4 “enabling inputs for quality education” include teaching and learning materials, physical infrastructure and facilities, human resources (teachers, principals, inspectors, supervisors, and administrators), as well as school governance.

Human Resource Motivation and Performance Overview

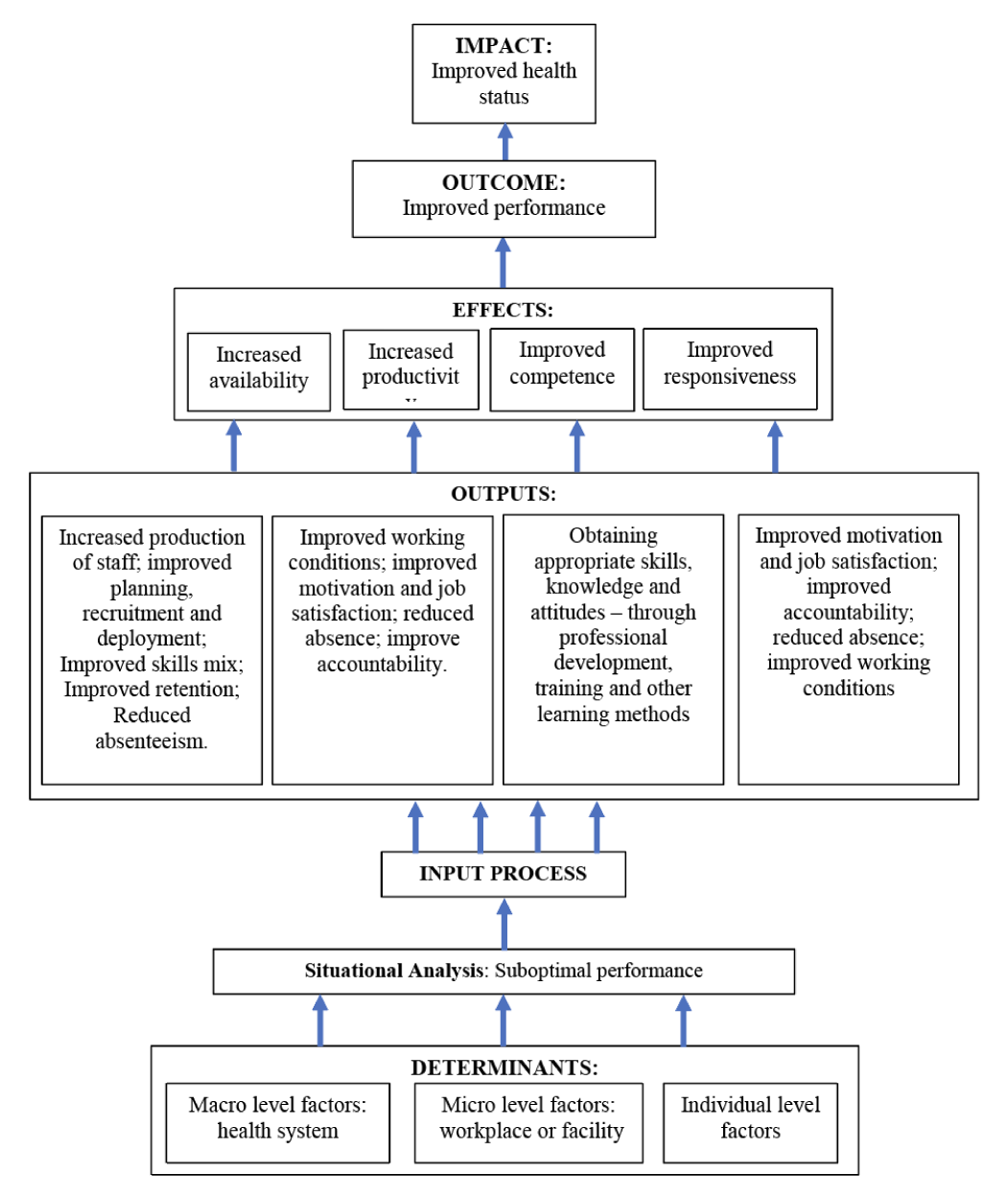

Worker performance is highly linked to worker motivation due to the labor-intensive and interpersonal nature of the services being provided. The performance of health professionals (though relevant to education professionals as well) has been defined as being available – retained and present – competent, productive, and responsive.5 A WHO framework for health worker performance and its link to motivation is in Annex 2.

Motivation has been defined as “an individual’s degree of willingness to exert and maintain an effort towards organizational goals.”6 This definition also frames motivation as being composed of two components: “the extent to which workers adopt organizational goals (‘will do’) and the extent to which workers effectively mobilize their personal resources to achieve joint goals (‘can do’).”

Herzberg7 provides a theoretical foundation for the determinants of motivation that is grounded in two types of factors:

| Dissatisfaction avoidance or hygiene factors | Growth or motivator factors |

|---|---|

|

|

While financial incentive levels and schemes may be important determinants of worker motivation, they alone have been found to be insufficient to keep health professionals motivated. A motivated worker must also have the right competencies, work environment, and resources to be high performing.5

Challenges in Human Resource Motivation and Performance

The challenges relating to human resource motivation and performance in health and education systems are considerable.

- Absenteeism: Many countries have epidemic levels of teacher and health worker absenteeism, particularly in rural and remote areas. A study in six developing countries found an average of 19% of teachers and 35% of health workers were absent during regular working hours.8 In India, more than 23% of teachers were absent during unannounced school visits, which was associated with an annual cost of $1.5 billion for services that were not delivered.9

- Professional attrition and “brain drain”: Teacher attrition rates in sub-Saharan Africa are variable but high—between 5-30%,10 and yet demand for teachers in low-resource countries is expected to grow dramatically in the years ahead, nearly doubling by 2030.11 Similarly, for health professionals in LMICs, migration to urban areas or higher-resource countries is mostly unplanned, leading to a “brain drain” of talented professionals and exacerbating shortages in resources in health. Despite efforts by the WHO to curb this trend, physician density is still declining in the majority of African countries and physician migration is on the rise.12

- Low technical competences in teaching and care: A study of nine sub-Saharan African countries using Service Delivery Indicators (SDI) found very weak rates of adherence to clinical guidelines. Less than a third of providers adhered to guidelines for neonatal and maternal health complications, and 35.9% adhered to guidelines for diarrhea, pneumonia, and malaria, with a diagnostic accuracy for these conditions of only 50%. Similarly poor guideline adherence was found in studies in health centers in India.13 Concerns also exist with the quality of teaching. The Learning Barometer survey of student performance, carried out in 28 African countries with primary school-age learners (Grades 4 and 5), identifies the proportion of children who meet a minimum learning threshold. It found that over a third of students—23 million children—fell below the minimum learning threshold, meaning most will be “unable to read or write with any fluency, or to successfully complete basic numeracy tasks.”14

Root Causes of These Challenges

Several of the root causes of the aforementioned challenges are described below.

- Inadequate initial professional training: Many teachers graduate from their training lacking information on what their pupils are supposed to learn and basic teaching and curricular management skills.14 Training programs for health care professions also suffer from chronic under-investment.15 A survey of medical schools across Africa found “ubiquitous faculty shortages in basic and clinical sciences, weak physical infrastructure, and little use of external accreditation.”16

- Difficult working conditions, including insufficient physical and supportive infrastructure: Schools and health centers, particularly in rural areas, can lack the very basics such as running water, consistent electricity, and adequate sanitation facilities.17,18 Access to decent housing and family-centered services (schools, daycare) outside of urban areas is also a major challenge for many professionals in education19 and health,20 particularly for women.

- Lack of work materials and essential supplies: (discussed in the following section)

- Increasing workloads: Pupil to Teacher Ratios (PTR) have increased dramatically following the roll-out of Universal Primary Education policies. This has meant overcrowded classrooms, more teaching periods, and more non-teaching activities.17 The global needs-based shortage of health-care workers is projected to be 14 million by 2010. When taking into account population size, the most severe challenges are in sub-Saharan Africa, where ratios of health professionals to patients are predicted to worsen between 2013 and 2030.15

- Low and unreliable remuneration: In many countries, teachers and health care providers do not earn enough to live above the poverty line, requiring many to turn to other part-time work to supplement their income.5,19 They may also experience delays in receiving their salary and be required to travel long distances to receive it.17

- Lack of constructive supervision, professional recognition or professional development opportunities: Education systems in many countries report having infrequent or ineffective supervisory visits. Teachers also generally receive very little feedback, support, or advice from more senior teachers or school administrators on how to improve.14 Similarly, health professionals have often limited access to professional development opportunities, which tend to be unevenly distributed despite high demand.17

Policy Options to Improve the Motivation and Performance of Human Resources

Below is an overview of policy options that could be considered to improve the motivation and performance of health and education professionals.

It must be noted that worker motivation is sensitive to system-wide or facility reform processes which can affect organizational dynamics, reporting, accountability and incentive structures. These changes may elicit a range of responses from professionals as they often require the development of new workforce capabilities and can affect different health system cadres differently.6 The involvement of health workers in the design and implementation of reforms has been found to be an effective way to manage these concerns.5

Policies to improve motivation and performance can be undertaken at the macro-system level or at the micro-facility level and can be designed to address performance issues by tackling “can do” or the “will do” gaps. They can also address the living conditions of health workers in ways that are adapted to the context, including rural location, age and gender considerations.5

Option 1. Changes to Payment and Reward Systems

Creating stronger linkages between payment and performance indicators can be an important way to improve the quality of professional work. The implementation of reforms to payment schemes requires careful consideration of bureaucratic and political economy considerations, such as resistance from unions, and the required data collection infrastructure.21

- Health worker performance-based financing (PBF or P4P) schemes: PBF is a contracting mechanism designed to increase the performance and quality of service providers by offering financial incentives to health facilities for the provision of a defined set of services, with adjustments based on measures of quality. These vary considerably in their format (payment structure, target services, etc.) and effect on employee performance and health outcomes.22 In the past decades, PBF schemes have generated substantial interest among policy-makers, donors and international organizations; as of 2015 a dedicated trust fund at the World Bank alone supported 36 PBF programs.23 Conditional cash transfers, modified by quality measurements, were found to be particularly effective in Rwanda – where P4P was found to have a positive effect on health care utilization, quality of care and outcomes, as well as on lowering worker absenteeism.24-27

-

Teacher performance pay schemes: Numerous schemes exist to reward teachers based on specific measures of performance and outputs. Studies in Tanzania, India and China generally found these approaches to be effective when combined with providing resources such as unconditional grants or textbooks.25,28,29 However, several other evaluations showed either no or marginally positive gains from such measures, especially for low-performing schools. It was also found that rewards may have detrimental effects, such as diminishing peer collaboration, narrowing the curriculum, and over-emphasis of teaching to the test. Generally, these schemes remain relatively rare at scale – a review found that only 17 of 101 education systems used test scores to formally sanction or reward schools or educators.30

- Benchmarking: Payments are based on the number of students that reach specific proficiency levels. This was found to be easier to communicate and implement,31 but difficult to sustain.32

- Pay for Percentile: Payments are based on students’ test scores relative to other students at the same starting level or similar students in other schools. This is harder to implement but incentivizes teachers to improve learning across the entire student distribution.33

- Special awards for teaching quality: Particularly when recognizing collaborative work among teachers, as research has found that monetary incentives are more effective when awarded to teaching teams compared to individual teachers.34

Option 2. Changes to Recruitment and Deployment

Macro-level policies can aim to improve education and health workforces by targeting who is recruited into key professions, how they are trained, and where they are deployed to work.

- Higher standards for recruitment: Setting higher minimum qualifications to enter the teaching or nursing profession, such as an undergraduate degree, could be an effective way to improve the status of the profession as well as to attract high-performing individuals. A merit-based appointment system, such as one implemented in Pakistan for teacher recruitment, included a test administered by a third-party National Testing Service to protect the system from political influence.35

- Measures to attract and retain professionals in understaffed rural areas: Several initiatives have been found to be effective for health care workers, including providing preferential admissions to students from rural areas, designing a “rurally oriented curricula” with a focus on rural health issues, imposing compulsory training rotations in rural settings, as well as providing scholarships, financial incentives, professional advancement, support networks, and help with setting up medical practices in rural areas.20 In education, other non-monetary incentives have been used, such as offering bicycles, housing, and preferential access to resources and training. “In the short term, the provision of good quality housing with running water and electricity for teachers is probably the most cost-effective way of attracting and retaining teachers at hard-to-staff rural schools.”19

- Diversification of the health and education workforce: To minimize the time spent by teachers on non-teaching activities, it is possible to include pedagogic assistants, health practitioners, and administrative support.11 Similarly in health care, shifting tasks between health care workers (“task sharing”) and expanding the clinical team, particularly to include community health workers, can relieve short-term human resource limitations.18

Option 3. Enhanced Professional Development Programs

Opportunities to improve existing or develop new technical skills are often a major source of motivation for professionals in health and education, and they also directly address the “can do” gap that inhibits performance.

- In-service or facility-based skills-development programs: Training is best when done close to practice where learners can immediately apply concepts and receive feedback. Meta-analyses show that successful in-service teacher training, coupled with ongoing monitoring, mentoring, and coaching, is a proven way to improve primary school teachers’ instructional practice in LMICs.36,37 Such approaches are generally more expensive but preferable to external continuing education programs or training-of-trainers cascade models, which have the disadvantage of being expended on a small minority of professionals who are withdrawn from their work.38

- Training and skills-building programs specific to management professionals: In addition to frontline workers, initiatives to develop the skills of managers are an important part of improving overall system quality. Health facility management training and supervision were found to be effective at improving organizational practices and health outcomes but needed to be ongoing.39 Training programs for headmasters in school management and leadership were also found to be effective across 13 countries at improving teacher motivation and performance.19,34

- Technology-enabled training and support: Some initiatives, such as technology-assisted professional development and text-message support, have been used to effectively reach teachers in remote areas.40,41

Option 4. Integration of Technology into the Classroom or the Clinic

Technological innovations, from apps to integrated teaching and learning systems, are multiplying in health and education spaces. These present great opportunities for improved performance, but also require significant investments and infrastructure. Across many developing countries, the rate of internet connectivity in schools is less than 10%. There is some concern that uneven access to these resources could exacerbate existing learning inequalities between rural/urban or affluent/resource-constrained areas.11 Nevertheless, technological innovations have been deployed to achieve a number of goals.

- “Blended-learning classrooms”: This format combines learning using technology with face-to-face teaching and was found to be effective in several case studies.41

- Technology for improved attendance monitoring: Different approaches have been tried to reduce absenteeism, including using sophisticated surveillance technology or simple mobile phone text systems. Biometric attendance monitors in primary health centers or cameras in schools in India were only found to be effective when attendance was linked to rewards or penalties and there was sufficient buy-in from the stakeholders involved in these processes.42 Other simple phone-based platforms to send daily data on teacher attendance were found to be effective in the Gambia and Zimbabwe.43

Procurement, Supply Delivery and Management Overview

Functioning procurement, supply delivery, and management systems are essential for quality health and education service delivery. A supply chain encompasses an “ecosystem of interlinked organizations, people, technology, activities, information, and resources” that is required to get products from manufacturers to users in the most cost-effective way possible. This includes inventory management, storage, distribution, and inventory control, and requires a large, competent, and properly trained workforce. Supply chains do more than simply delivering products, they also produce critical information related to the need, demand, and consumption to national and regional level planners.44

Procurement and Supply Chains in Health

The structure of supply chains for health varies greatly depending on national health system characteristics, such as the different sources of financing, risk pooling and purchasing, as well as national pharmaceutical regulations and treatment-seeking behaviors of patients. Supply chains play a role in many dimensions of health system performance: payment, organization, regulation, and also behavioral aspects of the health system.44 In the coming decades, as many global health initiatives such as GAVI, the Global Fund, and PEPFAR roll back their support, many LMICs will need to play a larger role in the procurement of health products.45

Procurement and Supply Chains in Education

Access to appropriate learning materials is listed as a key strategy for achieving SDG4 – particularly the dimension related to providing inclusive and effective learning environments for all.3 Textbooks are a particularly important input for improving learning outcomes in contexts with large class sizes, under-qualified teachers, and shortened instructional time. They have been found to be, when they are in the appropriate language and level of difficulty, a particularly cost-effective input with high returns in student achievement.30 A multi-country study of 22 sub-Saharan African countries found that providing one textbook to every student in a classroom increased literacy scores by 5–20%.46

Challenges in Procurement, Supply Delivery and Management

Supply chains can significantly affect the availability, price, and quality of strategic inputs. However, many national procurement and supply chain systems remain ineffective and poorly managed.

- Lack of availability of working materials and supplies: Key health system inputs, such as medicines, are not consistently available in many low-resource settings. According to an analysis of WHO data, the average availability of generic medicines in the public sector ranges between 29% to 54% across WHO regions.47 Interruptions in the access of medications are an important threat to public health, as they interfere with treatment initiation or continuity and increase the likelihood of ill health and antimicrobial resistance.45 Similarly, the procurement and supply of essential learning materials, particularly quality textbooks, remains a challenge in many LMICs. Between 2000 and 2007, rapid enrollment increases were experienced across several LMICs; however, textbook availability could not keep up. For example, in Malawi, “the percentage of students who either had no textbook or had to share with at least two other pupils increased from 28% in 2000 to 63% in 2007.”46 Gaps in essential school supplies are even more pronounced in rural or underserved areas.

- Inflated prices: Across LMICs, the prices of many vital inputs for health and education systems can be variable and disproportionately high. According to an analysis of WHO data, median government procurement prices for 15 generic medicines are 1-11 times international reference prices, and procurement prices that were low did not always translate to lower patient prices. This created a situation in which “treatments for acute and chronic illness were largely unaffordable in many countries.”47 The cost of textbooks varies greatly by country and region. In sub-Saharan Africa, the unit cost of a primary school textbook is between US$2 and US$4 compared to Vietnam, which produces books domestically, where the cost is between US$0.33 and US$0.66.46

- Poor quality of products delivered to end-users: Dysfunctional health product procurement and supply chain systems are associated with an increased risk of substandard quality or counterfeit drugs, which can lead to poisoning, ineffective treatments, and anti-microbial resistance.48 It is estimated that 1 in 10 medical products in low- and middle-income countries is substandard or falsified.45 In education, some national regulatory bodies lack a reliable process to evaluate the quality of textbooks, resulting in the use of substandard materials and production and errors in the content.49 The provision of quality textbooks in the correct language should be prioritized in early grades as this is when they have the largest impact on learning. However, in Chad, a 2010 survey found that only 20% of students had a textbook in the correct language of instruction (French) in grade two, and 40% of students in grade five.46

Root Causes of These Challenges

Weaknesses in national supply chain and procurement systems in health and education have several root causes.

- High production and import costs: The reasons for variations in the cost of textbooks across country and region include “fluctuating prices for raw materials, manufacturing, procurement, publishing overheads, distribution and storage, importation, and shipping.”46 In the health systems of many countries, depending on the size of the market and regulatory environment, importers and wholesalers of health products are numerous and fragmented, which significantly drives up prices. For example, there are 292 licensed medicine importers in Nigeria and 166 national wholesalers in Ghana.44

- Inability to correctly predict needs: The capacity to effectively forecast procurement or requisition materials is often deficient, particularly at decentralized levels. Accurate data estimating needs and consumption rates are fundamental to the effective management of procurement and distribution processes, and yet they are often unavailable or unreliable, resulting in stock-outs or waste.44,46 In most national health systems in LMICs “there are no processes by which information about consumption is systematically captured” – with many systems relying instead on “ad hoc surveys.”44

- Poor storage conditions and theft: Inappropriate distribution, storage, and usage conditions have been found in some cases to lead to an annual loss rate of 50% for textbooks. Moreover, poor security during transport and storage allows school supplies, particularly books, to be stolen and resold in the black market. A 2010 survey in Ghana found that 29% of English textbooks went missing during this process.46 Similarly, product diversion is a major driver of drug stock-outs in LMICs. The complexity of drug distribution systems can create many opportunities for diversion; in Kenya, for example, “medicines can change hands ‘five to seven times’ before reaching local clinics.”45

- Inefficient transportation: The lack of a well-functioning and managed government transportation fleet is a major barrier to effective supply chains in health. Vehicles for medication distribution are often unavailable due to lack of appropriate planning, poor maintenance, and inappropriate use.44

- Underlying weakness of the accountability structure: These weaknesses may be a result of fragmented responsibility and governance at different levels. Furthermore, the enforcement of supply chain and distribution regulations may be hampered by underfunding and limited human resource and organizational capacity, as well as inadequate supervision and corruption.44

- Unpredictable financing: The predictability of financing for the procurement of textbooks is very important because their development, production, procurement, and distribution is a long process. However, this is the case in only a few LMICs.46 In health systems, delays in the disbursement of funds from national finance bodies or international donor agencies often result in disruptions that ripple down the supply chain.44

Policy Options for Improved Supply Chain and Procurement

There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to improving the performance of procurement and supply chain systems. There are only a few well-designed randomized or quasi-randomized studies that demonstrate effective reforms to improve health system supply chain performance. The external validity of what evidence exists is reduced by the context-specific and complex features of national supply chain systems across countries.50 Nevertheless, some promising policy avenues exist and are described below.

Option 1. Procurement from Different Actors

Working with different actors for the procurement of key inputs in health and education systems may provide opportunities to improve the performance of procurement and supply chain systems. In health systems, however, the flexibility to work across different producers may be more limited.

- Regional or national production: Depending on the context and the product being procured, these may provide cost savings compared to international producers in relation to competition, taxes, import duties, and transportation. In Viet Nam, for example, the unit price for books is much lower than in many sub-Saharan African countries because it prints books domestically and fosters competition among publishers to drive down prices.46

- Procurement from the private sector: Turning to the private sector for textbook procurement is something some countries have done to try to drive down costs. For example, in 2002 Uganda began working with a private publisher through a competitive process and “saw the cost of textbooks fall by two-thirds and their quality increase.”46 However, other studies in Ghana, Tanzania, and Kenya suggest that there is little effect on the inefficiency, corruption, and lack of transparency from changing from state-controlled to private sector textbook provision.51

- Pooled funding mechanisms for improved predictability: These kinds of systems could provide more and predictable funding for textbooks; however, the current pooled funding mechanism for education, the Global Partnership for Education (GPE), has not had the same success as pooled funds in other sectors, such as GAVI health, in attracting more and predictable funding.46

Option 2. Re-Design the Procurement and Supply Systems

There are several potential ways to restructure these processes to make the best possible use of limited resources.

- Centralized procurement and tendering processes: This can help to create economies of scale and improved purchasing power. Such reforms were found to produce cost savings in a number of case studies from different regions, including the Middle East, Brazil, Mexico, and several countries in Asia and Africa.50

- Streamlined tiers of the supply chain system: Some countries have sought to decentralize procurement and supply processes to lower levels of the system, to provide additional flexibility, autonomy, and speed for purchasing at local facilities. However, in some cases, this has led to worse outcomes.44 In contrast, a quasi-randomized study in Zambia resulted in large improvements in medical product availability by cutting out the regional distribution step. Multiple modeling studies have also confirmed the benefits of reducing tiers in the supply chains for vaccines and immunization supplies.52 The decentralization of the supply of textbooks has also had mixed success with some countries, like Uganda, preferring instead to centralize procurement to combat corruption and mismanagement at the school and district levels.30

- Reduced number of wholesalers or middle-men: A smaller number of wholesalers is generally preferable for optimal supply chain performance, since fewer larger wholesalers gain economies of scale in their distribution efficiency and have improved access to capital for infrastructural investments. The creation and enforcement of regulations around quality standards and distribution practices can lead to the consolidation of smaller players, although the resistance from smaller actors who stand to lose from this type of reform may be prohibitive.44 The cost of distributing textbooks can contribute to high variations in price, as seen when comparing Kenya and Rwanda. Although both countries use a commercial distribution system to deliver books, the unit textbook cost in Kenya is nearly double that of Rwanda, partly because Kenya delivers books through a bookseller middleman rather than having publishers deliver directly to schools.46

- Public-private partnerships: Several effective partnerships have been established, particularly those which involve the contracting of private operators for the last-mile delivery of products. Large multinational companies partnering to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of supply chains in LMICs include Coca-Cola and the UPS Foundation.49,53

Option 3. Improved Distribution Processes

At different points in the supply chain process, improvements can be made to improve forecasting capacity, replenishment systems, as well as product transportation and traceability.

- Improved stock-management and procurement request practices: Simple technology and software can be used to track consumption and demand—to know when stocks are running short and to update them faster. If such systems are not able to be put in place, particularly in areas with poor technology infrastructure or IT connectivity to carry out stock requisitioning, it is possible to combine information collection with product distribution. Such systems were found to be effective in Zimbabwe and Mozambique.44

- Reduced lead-times from suppliers and increased frequency of replenishment: Increasing replenishment frequency “increases the speed and velocity of the supply chain and decreases the reliance on long-term forecasts,” approaching actual levels of demand. However, this can lead to higher transport costs, and therefore statistical modeling should be used to determine the best balance between transport costs and benefits from forecast improvement.44

- Digital technologies that help “track and trace” the movement of products: In addition to improved security throughout the storage and transportation process, unique serial numbers at the package level can be a good defense against theft during the distribution chain.48 “Track and trace initiatives allow actors on a supply chain to determine where a product is at any given time (tracking) and where it came from (tracing). The approach starts with the process of serialization, in which a manufacturer assigns a unique identifier to each product that it ships using a two-dimensional (2-D) barcode that other supply chain actors can scan to obtain information about the product and record when it changes hands.” This creates a digital trail of information linking each package along its path through the supply chain for increased accountability.45

- New or outsourced delivery methods: “Depending on the geography, overall economic situation, maturity of the transport market and structuring of the price and service level contracts, a third-party logistics provider can offer better service at rates comparable to the fully loaded cost of owning and operating a government fleet.” In the case of Kenya, this approach helped to address problems with transport planning, vehicle maintenance, and inappropriate use.44 Leapfrogging using novel delivery technology is also possible, such as using drone delivery for emergency supplies or deliveries in hard-to-reach areas in Rwanda.54

Option 4. Invest in Human Resources and Management Tools

Recruiting talented supply chain experts into the public sector is important for high levels of financial and operational performance. Management and leadership roles in this sector should not only be restricted to civil servants but also include individuals with strong commercial sector experience.

- Professional development for procurement and supply chain professionals: Several countries have successfully implemented comprehensive short-term training programs aimed at procurement practitioners, members of tender committees, tender review boards, and oversight institutions. As procurement and supply chain processes become increasingly technology-driven, it is equally important for practitioners to also expand their expertise in business engineering and design and information technology.55 Other effective quality improvement interventions focused on improving teamwork and the human elements of supply chain management.50

- Benchmarking tools to improve performance: These tools can also help to standardize supply chain performance metrics such as Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA).

Data for Decision Making Overview

Data is a fundamental part of strategic, goal-oriented, and effective systems. “Data-informed decision making” is a process that is proactive and interactive, and that “consider[s] data during program monitoring, review, planning, and improvement; advocacy; and policy development and review.”56

For data to be used for decision making, it should be accurate, timely, disaggregated, and widely available, as well as made actionable through analysis.57 Given the ambitious vision of the SDGs—with 17 goals, 169 targets, and 232 indicators to be achieved by 2030—there is a great need for quality data for monitoring and measuring progress.58

Challenges with Using Data for Decision Making

There have been gains in the frequency and quality of censuses and household surveys, however, many of the “building blocks” of national statistical systems remain weak. Importantly, this gap includes data that is central to estimating “almost any major economic or social welfare indicator—[such as] data on births and deaths; growth and poverty; taxes and trade; sickness, schooling, and safety; and land and the environment.”57 The inadequacy and unreliability of official statistics in many Sub-Saharan African countries have led to the U.N. High-Level Panel on post-2015 development goals calling for a “data revolution” to improve tracking of economic and social indicators across the developing world.59

Data in Education

Behind the learning crisis in much of the developing world is a huge data gap. Only a few middle-income developing countries have the political incentives and technical capacity to develop and sustain national data systems for education. Countries in the developing world rarely have the infrastructure of data collection in place, nor the capacity to analyze and feed information back to educators, parents, and communities. International assessments and regional initiatives cover relatively few developing countries; the majority of school children in the developing world are not tested at all. Moreover, while there is a range of data sources on education systems, services, and outcomes, these are not always translated into user-friendly formats for decision making.60

School-level enrollment statistics are necessary to make efficient staffing decisions, however, in some countries, like Kenya, this information is only available from the country’s Education Management Information System (EMIS) three times a year.59

Data in Health

Quality and timely data from health information systems are the foundation of the health system and inform decision making in each of the other five building blocks of the health system. Recent years have witnessed significant commitments to and investments in the strengthening of information systems.56 However, data quality and the availability and demand for timely analysis for decision making remain problematic.

- Poor quality data: Many LMICs continue to face challenges related to the poor quality of routinely collected data. Comparing administrative and survey data of primary school enrollment in 46 surveys across 21 African countries found a bias toward over-reporting enrollment growth in administrative data—with an average change in enrollment nearly one-third higher in administrative data. “Many countries’ health management information systems (HMIS) databases rely on self-reported information from clinic and hospital staff, which aggregated up by district and regional health officers, each with potentially perverse incentives.”59

- Under-resourced and under-staffed national statistical agencies: The high turnover of qualified EMIS staff, particularly in Ministries of Health, is a recurring challenge in LMICs, largely due to the low and relatively unattractive salaries.58 These agencies have also failed to improve significantly over time due to a lack of functional independence, as well as being reliant on volatile donor funding.59

- Fragmented and inadequate information systems: Electronic Medical Information Systems (EMIS) in many sub-Saharan African countries are “chronically weak,” with problematic or at times absent key functions such as data entry control, import-export, data consolidation, consistency checks, and data extraction, estimation and imputations, projections, or archiving facilities.58

- Limited capacity for analysis and use of data at local levels: All too often, data remains unutilized, sitting in reports, on shelves, or in databases and not being used in program development, quality improvement, policymaking, or strategic planning.56 In a survey of several tiers of Ethiopian government officials, only about 12% of officials stated that they used national information management systems as their primary source of information, preferring instead “formal field visits” (63%) or informal informational interactions such as discussions with frontline colleagues (51%) or colleagues in their organization (45%). Reliance on these more informal information sources was found to lead to only a minority of officials being able to make “relatively accurate claims about their constituents.”61

Root Causes of These Challenges

Challenges related to data for decision making are not merely technical but rather the result of implicit and explicit incentives and systemic challenges, including a lack of stable funding for national statistical systems and minimal checks and balances to ensure that the data are accurate and timely.57

- Dominance of donor data priorities over national priorities: “The different needs of donors and government present trade-offs between the comparability, size, scope, and frequency of data collection. Given that donors finance a large share of spending on statistics, these differing needs can imply that national statistical systems aren’t built to produce accurate data disaggregated for use by domestic policymakers and citizens.” An example of this is the DHS in Tanzania, which reported results for seven aggregate zones that did not correspond to any practical local unit of measure or political accountability.59

- Weak demand for data from users: Data are not consistently utilized by senior officials and policymakers within ministries of health and education for a number of reasons. This can be due to a lack of capacity to make data available or “because senior ministerial staff choose not to use data that contradict official views or out of fear it will damage their credibility or subject them to heavy pressure from the executive branch of government.”58

Policy Options for Data-Driven Decision Making

Option 1. Improve the Quality of Data

This can be achieved a number of ways, including through stronger systems, better monitoring, and by reducing the incentives to misrepresent data.

- Better funding national data collection systems: Improving the funding levels and structure of national statistical systems and organizations could help to improve their performance. Also consider increasing domestic funding allocation for National Statistical Offices, mobilizing more donor funding through government–donor compacts, and experimenting with pay-for-performance agreements.57

- Improved data collection and reporting accuracy through enhanced data audits: Facility-level technology can be used to support more frequent quality audits of routinely collected data. Regular data audits by an independent third-party verifier are a central part of PBF systems to attempt to overcome asymmetric information between the providers and payers, create accountability, and minimize gaming. Effectively targeting these verification activities can help to balance the costs and benefits of having a large enough sample to carry out effective verification activities.23

- Integrating different data streams: Redesigning data systems for improved accountability could also be achieved by getting administrative and survey data to “speak to each other,” whereby household surveys can be used to provide regular checks on administrative data at different levels.59

Option 2. Strategically Selecting Data to Collect

The effort to generate data for international goals should not displace the focus from building the capacity of national statistical agencies.

- Diversifying and prioritizing indicators: Health and education systems should identify and prioritize key indicators for tracking progress toward SDG targets as well as answering questions of national relevance.62,63 For measurement to promote accountability and quality improvement, it must capture the processes and outcomes that are most important to people. In many cases, data systems produce metrics that yield inadequate insight at a substantial cost both in terms of finances and front-line workers’ time. For example, a frequently used indicator is the proportion of births with skilled attendants, however, this does not adequately reflect the quality of care during childbirth and therefore may deceptively represent progress in maternal and newborn health.1

- Introduce internationally recognized standard measures: Currently, few countries in the sub-Saharan African region perform international learning assessments of their students,1 and most collect learning data in a “fairly haphazard fashion.”14,60 Most school children should be able to take a test that can be compared year over year or globally benchmarked. Policymakers and citizens need a basis to assess the quality of schooling.

Option 3. Improve Demand for Data from Decision Makers

To improve the use of data at all levels, data systems and tools can be put into place.

- Develop decision-maker facing data dashboards: To complement smaller initiatives to present data to decision makers, other larger dashboards or toolkits have been introduced, including the World Bank’s multidimensional Global Education Policy Dashboard and the “Data4SDGs Toolbox,” which seeks to help countries “create and implement their own holistic data roadmaps for sustainable development.”64

- Data briefs or review meetings: For data to be understood and digestible by potential users, they must be synthesized and disseminated in formats that are specific and adapted to users. Different targeted information products, focusing on “need to know” information, could include standardized reports and presentation templates for regular dissemination and feedback to decision makers.56 “External briefings” were found to significantly reduce errors made by officials, particularly in contexts where organizational incentives for data use were in place.61

- Targeted capacity building for data utilization: These efforts can include ministries, national institutes, academia, and other stakeholders. Better linking the data producers with data users, who may otherwise be working at different levels of the health system and have an incomplete understanding of each other’s needs and roles. By addressing barriers to data use together, producers and users of data can also identify programmatic priorities and make data available to work on them.56,59

1 International assessments and regional initiatives such as LLECE in Latin America (Latin American Laboratory for Assessment of the Quality of Education) or PASEC (Program for the Analysis of CONFEMEN Education Systems) and SACMEQ (Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality) in Africa, cover relatively few developing countries (Source: Birdsall, 2016).

Annexes

Annex 1: Summary Table of Challenges and Policy Options

| Strategic Area | Major Challenges | Root Causes of the Problems | Policy Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Resource Motivation and Performance |

Absenteeism Professional attrition and “brain drain” Low technical competences in teaching and care |

• Inadequate initial professional training; • Difficult working conditions, including insufficient physical and supportive infrastructure; • Lack of work materials and essential supplies; • Increasing workloads; • Low and unreliable remuneration; • Lack of constructive supervision, professional recognition or professional development opportunities. |

Option 1: Changes to payment and reward systems • Health worker performance-based financing (PBF or P4P) schemes; • Teacher performance pay schemes. Option 2: Changes to recruitment and deployment: Option 3: Enhanced professional development programs Option 4: Integration of technology into the classroom or the clinic |

| Procurement, Supply Delivery and Management |

Lack of availability of working materials and supplies Inflated prices Poor quality of products delivered to end-users |

• High production and import costs; • Inability to correctly predict needs; • Poor storage conditions and theft; • Inefficient transportation; • Underlying weakness of the accountability structure; • Unpredictable financing. |

Option 1: Procurement from different actors • Regional or national production; • Procurement from the private sector; • Pooled funding mechanisms for improved predictability. Option 2: Re-design the procurement and supply systems Option 3: Improved distribution processes Option 4: Invest in Human Resources and Management Tools |

| Data for Decision Making |

Poor quality data Under-resourced and under-staffed national statistical agencies Fragmented and inadequate information systems Limited capacity for analysis and use of data at local levels |

• Dominance of donor data priorities over national priorities; • Weak demand for data from users. |

Option 1: Improve the quality of data • Better funding national data collection systems; • Improved data collection and reporting accuracy through enhanced data audits; • Integrating different data streams. Option 2: Strategically select data to collect Option 3: Improve demand for data from decision makers |

Annex 2: Framework for Analysis of Motivation

Source: Adapted from “Improving health worker performance: in search of promising practices” by Marjolein Dieleman and Jan Willem Harnmeijer (WHO, 2006)5

References

- Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. The Lancet Global Health. 2018;6(11):e1196-e1252.

- UNDP. Goal 3: Good health and well-being. UNDP.org. Sustainable Development Goals Web site. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-3-good-health-and-well-being.html. Published 2019. Accessed May, 2019.

- UNDP. Goal 4: Quality education. UNDP.org. Sustainable Development Goals Web site. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-4-quality-education.html. Published 2019. Accessed May, 2019.

- UNESCO. Education for all: the quality imperative; EFA global monitoring report 2005; summary. France: UNESCO; 2004.

- Dieleman M, Harnmeijer JW. Improving health worker performance: in search of promising practices. Geneva: WHO; 2006.

- Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R. Health-sector reform and public-sector health worker motivation: a conceptual framework. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;54:1255–1266.

- Herzberg F. One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees? Harvard Business Review. 2003(January):10.

- Chaudhury N, Hammer J, Kremer M, Muralidharan K, Rogers FH. Missing in Action: Teacher and Health Worker Absence in Developing Countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20(Winter):91–116.

- Muralidharan K. A New Approach to Public Sector Hiring in India for Improved Service Delivery: a Working Paper. 2016.

- UNESCO. Teacher motivation and incentives. UNESCO Learning Portal. https://learningportal.iiep.unesco.org/en/issue-briefs/improve-learning/teachers-and-pedagogy/teacher-motivation-and-incentives. Published 2018. Updated September 6, 2018. Accessed May, 2019.

- ICFGEO. The Learning Generation – Investing in education of a changing world. International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity; 2016.

- Cometto G, Tulenko K, Muula AS, Krech R. Health workforce brain drain: from denouncing the challenge to solving the problem. PLoS Med. 2013;10(9):e1001514.

- Fritsche G, Peabody J. Methods to improve quality performance at scale in lower- and middle-income countries. J Glob Health. 2018;8(2):021002.

- Watkins K. Too Little Access, Not Enough Learning: Africa’s Twin Deficit in Education. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/too-little-access-not-enough-learning-africas-twin-deficit-in-education/. Published 2013. Accessed May, 2019.

- WHO. Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

- Mullan F, Frehywot S, Omaswa F, et al. Medical schools in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet. 2011;377(9771):1113-1121.

- Evans DK, Yuan F. The Working Conditions of Teachers in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. World Bank; 2018.

- WHO. The world health report 2006: working together for health. World Health Organization; 2006.

- Bennell P, Akyeampong K. Teacher Motivation in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Department for International Development: Educational Papers. 2007.

- Dolea C, Stormont L, Braichet JM. Evaluated strategies to increase attraction and retention of health workers in remote and rural areas. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(5):379-385.

- Makhuzeni B, Barkhuizen EN. The effect of a total rewards strategy on school teachers’ retention. SA Journal of Human Resource Management. 2015;13(1).

- Witter S, Fretheim A, Kessy FL, Lindahl AK. Paying for performance to improve the delivery of health interventions in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(2):CD007899.

- Grover D, Bauhoff S, Friedman J. Using supervised learning to select audit targets in performance-based financing in health: An example from Zambia. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0211262.

- Abbott P, Sapsford R, Binagwaho A. Learning from Success: How Rwanda Achieved the Millennium Development Goals for Health. World Development. 2017;92:103–116.

- Mbiti I, Muralidharan K, Romero M, Schipper Y, Rajani R, Manda C. Inputs, incentives, and complementarities in primary education: Experimental evidence from Tanzania. World Bank; 2016.

- Gertler P, Christel V. Using Performance Incentives to Improve Health Outcomes. World Bank Policy Research Working Papers. 2012.

- CGD. Rwanda’s Pay-for-Performance Scheme for Health Services. Center for Global Development. http://millionssaved.cgdev.org/case-studies/rwandas-pay-for-performance-scheme-for-health-services. Published 2015. Accessed May, 2019.

- Muralidharan K, Sundararaman V. Teacher Performance Pay: Experimental Evidence from India. Journal of Political Economy. 2011;119(1).

- Loyalka P, Sylvia S, Liu C, Chu J, Shi Y. Pay by Design: Teacher Performance Pay Design and the Distribution of Student Achievement. Journal of Labor Economics. 2018.

- UNESCO. Accountability in education: meeting our commitments. UNESCO; 2018.

- KuiFunza. Teacher Incentives in Public Schools: Do they improve learning in Tanzania? Tanzania: Twaweza East Africa; 2018.

- Glewwe P, Ilias N, Kremer M. Teacher Incentives. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2010;2.

- Barlevy G, Neal D. Pay for Percentile. American Economic Review. 2012;102.

- Guajardo J. Teacher Motivation: Theoretical Framework, Situation Analysis of Save the Children Country Offices, and Recommended Strategies. Save the Children; 2011.

- WB. Pakistan: Qualified Teachers Become Integral to Punjab’s Public-school system. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/12/13/qualified-teachers-become-integral-punjabs-public-school-system. Published 2018. Accessed May, 2019.

- Ganimian AJ, Murnane RJ. Improving education in developing countries: Lessons from rigorous impact evaluations. Review of Educational Research. 2016;86(3).

- Wolf S, Aber L, Behrman JR, Tsinigo E. Experimental Impacts of the “Quality Preschool for Ghana” Interventions on Teacher Professional Well-being, Classroom Quality, and Children’s School Readiness. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness. 2019;12(1).

- Moon B. School-based teacher development in sub-Saharan Africa: Building a new research agenda. Curriculum Journal. 2007;18:355–371.

- Dunsch F, Evans DK, Eze-Ajoku E, Macis M. Management, supervision, and healthcare: A Field experiment. 2017. Located at: Discussion Paper.

- Jukes M, Turner E, Dubeck M, et al. Improving Literacy Instruction in Kenya Through Teacher Professional Development and Text Messages Support: A Cluster Randomized Trial. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness. 2016.

- McAleavy T, Hall-Chen A, Horrocks S, Riggall A. Technology-supported professional development for teachers: lessons from developing countries. Education Development Trust; 2018.

- Hanna R, McIntyre V. Implementation ups and downs: Monitoring attendance to improve public services for the poor in India. VoxDev. https://voxdev.org/topic/health-education/implementation-ups-and-downs-monitoring-attendance-improve-public-services-poor-india. Published 2017. Accessed.

- ADEA. Reducing Teacher Absenteeism: Solutions for Africa. Harare: Association for the Development of Education in Africa; 2015.

- Yadav P. Health Product Supply Chains in Developing Countries: Diagnosis of the Root Causes of Underperformance and an Agenda for Reform. Health Systems & Reform. 2015;1(2).

- Pisa M, McCurdy D. Improving Global Health Supply Chains through Traceability. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development; 2019.

- GEM. Every Child Should Have a Textbook. Global Education Monitoring Report; 2016.

- Cameron A, Ewen M, Ross-Degnan D, Ball D, Laing R. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: a secondary analysis. The Lancet. 2009;373(9659):240-249.

- IOM. Countering the Problem of Falsified and Substandard Drugs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

- Majeed R. Promoting accountability, monitoring services: textbook procurement and delivery, Philippines, 2002-2005. Innovations for Successful Societies; 2013.

- Seidman G, Atun R. Do changes to supply chains and procurement processes yield cost savings and improve availability of pharmaceuticals, vaccines or health products? A systematic review of evidence from low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health. 2017;2.

- Opoku-Amankwa K, Brew-Hammond A, Kande Mahama A. Publishing for pre-tertiary education in Ghana: the 2002 textbook policy in retrospect. Educational Studies. 2015;41(4).

- Vledder M, Friedman J, Sjoblom M, Brown T, Yadav P. Enhancing public supply chain management in Zambia. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2013.

- The Global Financing Facility, Merck for Mothers, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and The UPS Foundation Launch Public-Private Partnership to Improve Supply Chains in Low- and Middle-Income Countries [press release]. Washington DC; 2018.

- Zipline. Lifesaving Deliveries by Drone. https://flyzipline.com. Published 2019. Accessed May, 2019.

- Dza M, Fisher R, Gapp R. Procurement Reforms in Africa: The Strides, Challenges, and Improvement Opportunities. Public Administration Research. 2013;2(2).

- Nutley T. Improving Data Use in Decision Making – An Intervention to Strengthen Health Systems. USAID; 2012.

- Glassman A, Ezeh A. Delivering on the Data Revolution in Sub-Saharan Africa – Data for African Development Working Group Final Report. Center for Global Development; 2014.

- Baghdady A, Zaki O. Education Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Mastercard Foundation; 2019.

- Sandefur J, Glassman A. The Political Economy of Bad Data: Evidence from African Survey & Administrative Statistics. Center for Global Development; 2014.

- Birdsall N, Bruns B, Madan J. Learning Data for Better Policy: A Global Agenda. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development; 2016.

- Rogger DO, Somani R. Hierarchy and Information. Washington DC: World Bank; 2018.

- Masaki T, Custer S, Eskenazi A, Stern A, Latourell R. Decoding data use: How do leaders use data and use it to accelerate development? Williamsburg, VA: College of William & Mary; 2017.

- Demombynes G, Sandefur J. Costing a Data Revolution. Center for Global Development; 2014.

- GPSDD. Data4SDGs Toolbox. Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data. http://www.data4sdgs.org/initiatives/data4sdgs-toolbox. Published 2019. Accessed.