Introduction

In February 2017, Dr. Matthew Opoku Prempeh was appointed Ghana’s Minister for Education. From the get-go, the President of Ghana, President Nana Akufo-Addo, tasked him with delivering Free Senior High School (Free SHS) in the country, a program that would provide free education, paying for a total of 41 items, including tuition, meals, textbooks, and boarding for Ghanaian children qualified for secondary education.

This task was challenging. More than 100,000 additional students, who should have been attending senior high school, needed to be absorbed into the system annually. Classrooms, dormitories, science labs, ICT labs, and workshops for technical and vocational education and training (TVET) were in short supply, in addition to teacher shortages and poor-quality teaching in the secondary education system. There was also political opposition. Many in the opposition cited infrastructure gaps and concerns over quality teaching as reasons why Free SHS should not be on the Ghanaian agenda at the time. Nonetheless, by September 2017, just seven months after his appointment, Dr. Matthew Opoku Prempeh launched Free SHS nationwide and, consequently, increased SHS attendance.

How did Ghana manage to deliver Free SHS nationwide so quickly? What lessons can other political ministers draw about leadership, resource mobilization, stakeholder engagement, and organizing for results? This case study, built from extensive conversations with Minister Prempeh and his collaborators, uses the Harvard Ministerial Leadership Program’s framework to unpack the strategies, challenges, and decisions behind the Free SHS program led by Minister Prempeh, while inviting ministers to reflect on how to apply these lessons in their own contexts.

Leading with Clarity

Minister Prempeh’s appointment was not a surprise; President Akufo-Addo pledged free secondary school in his manifesto. “In 2012, during the election petition, the President told me that if we won, he wanted me to be Minister for Education,” Minister Prempeh recalls. “When we finally won in 2016,” he said, “For you, I haven’t changed my mind.” Despite his background as a medical doctor, a path somewhat unconventional for leading a Ministry of Education, Minister Prempeh accepted the President’s challenge and the confidence placed in him to lead Ghana’s education sector and achieve the President’s vision.

President Nana Akufo-Addo’s mandate for Minister Prempeh was clear. “He had looked at his team and said I had the energy and intellectual depth to handle his most important legacy policy: free secondary education,” says Minister Prempeh. Thus, he went on to adopt the President’s goal as his own mission.

The following quote from President Akufo-Addo’s speech, when launching the free SHS program in September 2017, and as highlighted by Minister Prempeh, is what largely motivated him to ensure the success of free SHS:

“A government may not be able to make every citizen rich. But, with political will and responsible leadership, a government can help create a society of opportunities and empowerment for every citizen, and I know no better way to do so than through access to education.”

After his swearing-in to office, the first person Minister Prempeh spoke to about his role as a government leader was the President himself:

“I went to him for a series of engagements to help me get a deeper and better understanding of his vision for education in Ghana, in general, and the free SHS, in particular. I also had discussions with the Vice-President, Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia, who had been with and shared the President’s vision right from the onset in 2008. He indeed helped me reshape my thoughts and psych myself up for the task ahead.”

Moreover, Minister Prempeh immediately set expectations with the President. “I told him, ‘This is life-transforming. What I need most is your backing 24/7 until we get it done.’ He promised, and he delivered. The President was with me throughout, meeting frequently, even deciding what would go into the Free SHS package,” he says.

Minister Prempeh saw his role as Minister for Education as more than a job. “I was in politics for the long term. I could not fail. Failure would not only kill the policy but also destroy my career. I treated this as a mission, not just a position.”

Clarifying Priorities

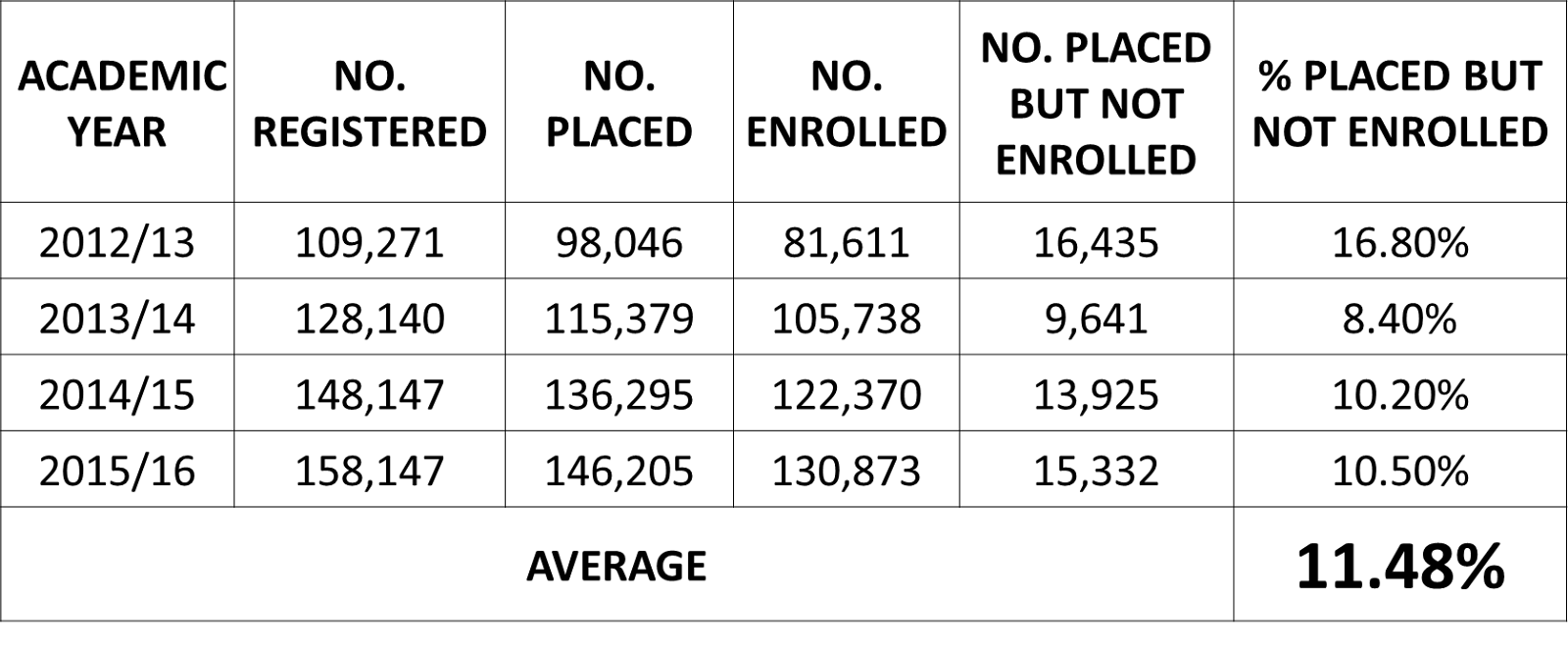

Data available to the Ghana Education Service (GES) and the Ministry for Education, at the time, pointed to the fact that the biggest barrier to SHS (Secondary High School) enrolment in the country was financial. Many did not attend SHS because they could not afford its cost. This was evidenced by the enrolment rates analysis of pre-Free SHS data when disaggregated for learners benefiting from the Northern Scholarships, and learners in the Southern part of the country who were not beneficiaries of the scholarship or bursary.

TABLE 1: NORTHERN SCHOLARSHIPS ADMISSIONS AND PLACEMENT TRENDS

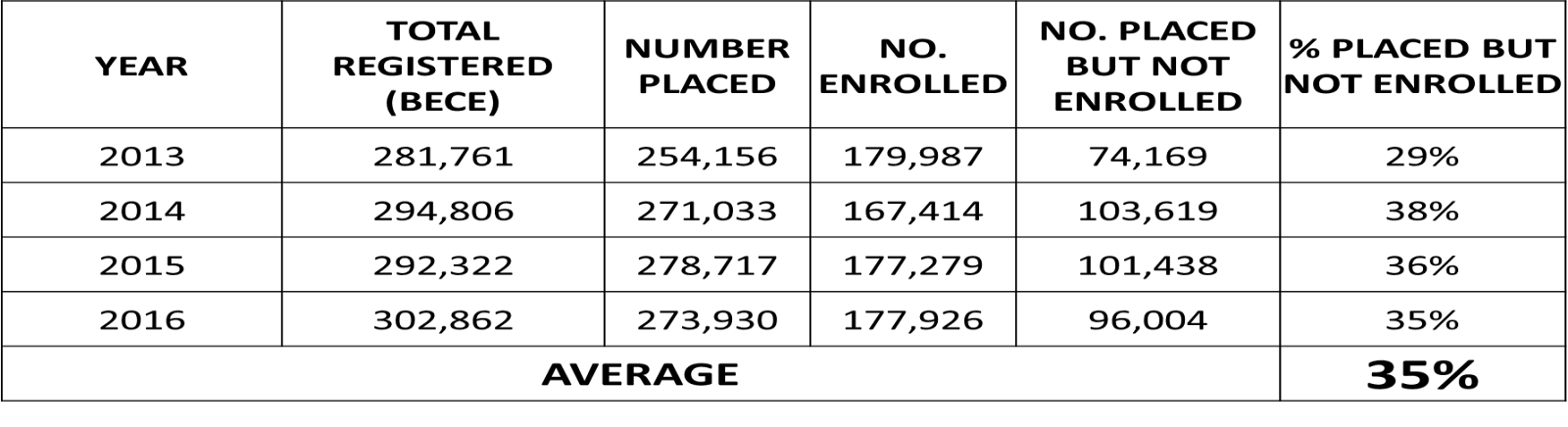

TABLE 2: SOUTHERN ADMISSIONS AND PLACEMENT TRENDS

Hence, “The free SHS was rolled out primarily to address inequality among students, through the removal of cost barriers whilst enhancing quality. We committed to creating a fair, safe and prosperous future for our citizens by providing equal opportunities for all,” Minister Matthew says. Moreover, to be effective in delivering free SHS, him and his team set four clear priorities and anchored them on four main pillars:

- Removal of Cost Barriers: Remove cost barriers through the absorption of fees approved by the Ghana Education Service (GES) Council.

- Access and Expansion of Infrastructure: Expand physical school infrastructure and facilities to accommodate the expected increase in enrolment.

- Improvement in Quality and Equity: Improve quality through the provision of core textbooks and supplementary readers, teacher rationalization and deployment, etc.

- Development of Employable Skills: Improve the competitiveness of Ghanaian Students to match the best in the World.

There is a reason why Minister Prempeh set priorities. From his perspective, priorities needed to be clear and set because “the goal was simple but massive”. This goal meant “full access to SHS up to age 18, at no cost, while maintaining quality. That meant new dormitories, classrooms, books, and teachers, all in months, not years.”

Moreover, these priorities drew on Ghana’s constitutional directive to expand free education as the economy allowed, and on global and continental targets, including SDG 4 (Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all) and the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Defined Legacy Goal

Minister Prempeh and President Akufo-Addo did not just frame Free SHS as a policy. They framed it as a legacy that would shape their country. In Minister Prempeh’s words, “over 100,000 junior high graduates could not continue to SHS each year, primarily due to cost. In northern Ghana, where partial scholarships existed, only 11% of qualified students missed school. In the south, without scholarships, 35% could not attend.” Therefore, reducing cost and improving access to secondary education were a priority and the transformative legacy goal the minister wanted to achieve. His own experience growing up in Ghana motivated him to work on this goal. For him, “the shortest bridge [he] ever crossed was between poverty and prosperity, and that bridge was education. Without it, the gap is a gulf. With it, the bridge is short.” President Akufo-Addo said:

“By free SHS, we mean that in addition to tuition, which is already free, there will be no admission fees, no library fees, no science center fees, no computer laboratory fees, no examination fees, no utility fees. There will be free textbooks, free boarding, and free meals and day students will get a meal at school for free.” 1

Defined Metrics and Delivery Unit

Minister Prempeh was appointed in February 2017, and Free SHS had to be launched in September 2017. With just seven months to launch, data monitoring and accountability were critical. Thus, Minister Prempeh constituted an advisory team, established a Free SHS Secretariat and a Delivery Unit, among other actions, to track every operational detail. He built these teams by closely collaborating with technical experts, such as Professor Kwasi Opoku-Amankwa, the Director-General of GES (Ghana Education Service), and indeed with heads of all the 26 agencies and their affiliates of the Ministry of Education. The GES is an agency under Ghana’s Ministry of Education that oversees the implementation of government policies to ensure that all Ghanaians receive formal education.

Together, “We built dashboards for each school,” Minister Prempeh explains. “We tracked classrooms, dormitories, textbooks, teachers, and feeding programs. We used a traffic-light system.”

Professor Opoku-Amankwa, who also acted as the technical advisor to the Minister for Education and the Government of Ghana on all matters relating to pre-tertiary education, explains how essential it was for the SHS Secretariat and delivery unit team to use data-driven tools to monitor free SHS outcomes and keep the program on track and accountable. He says:

“We put everything that we were doing into a table, and then we labeled them red, gold, and green. If it was green, it meant it was done. If it was red, it was outstanding. If it was gold, we were working on it, and we gave reasons for each status.”

This “traffic light” system created rapid feedback loops, with weekly updates to the Cabinet and, when necessary, escalations to the President’s office. It also created visibility across all program areas, from curriculum reforms and infrastructure development to teacher training and ICT rollout. By combining operational tracking (traffic light tables) with impact indicators (access, performance, and equity), the SHS program was able to identify gaps early, adjust quickly, and clearly communicate progress, setbacks, and program-related updates to stakeholders.

Cross-Collaboration & Stakeholders Mapping and Engagement

With a clear understanding of the President’s vision, and further details from the Vice President, Minister Prempeh’s next move was building a coalition across government and society to successfully implement free SHS. He says, “Ministers don’t connect to graphs; they connect to stories. So, we told a story about why Free SHS mattered, but we always backed it with hard data.” Therefore, he went on to have a series of engagements with virtually all colleague Cabinet ministers. He says:

“My view was that education affects and relates to all ministries. Every ministry has an input into education development. For example, I needed to secure the funds for free SHS from the Ministry of Finance. I had to talk to the Minister for Food and Agriculture on issues relating to food and manciple, while I talk to the Interior Minister on security and safety matters on our school campuses. There is a whole unit on school health programme in the Ghana Education Service. The unit works closely with a similar unit in the Ghana Health Service. I needed to talk to my colleague Health Minister, to ensure a seamless and collaborative work between the units.”

Professor Opoku-Amankwa added:

“The hon. minister used data and evidence-based research to effectively make a case for us all to participate fully in the President’s mission. Through a series of meetings and engagements, we developed a shared vision and implementation framework and communication plan to guide us. The hon. minister also communicated with us, the team, effectively the key objectives of the Free SHS and how free education has insured the success of many nations including the USA and most developed countries.”

Moreover, “The President himself met with the unions,” Minister Prempeh says. “We made sure everyone understood the vision, even if they didn’t fully agree.”

Minister Prempeh highlights the key stakeholders he included in this mission as follows:

- “I also needed the buy-in of my caucus members of parliament and the leadership and communication team of the governing party – the New Patriotic Party (NPP).”

- “I went beyond these internal party groups to engage the parliamentary committee on education.”

- “I constituted an advisory team which included a group of eminent educationists, academists, technical experts and entrepreneurs, industrialists.”

- “At the level of the ministry, I made sure we had a shared vision. I engaged and subsequently involved the leadership and management teams of all the twenty-six agencies under Ministry of Education. We worked together through a series of in house and out of office meetings to plan out the various reforms beyond the free SHS: curriculum reforms, teacher professionalization, infrastructure audit and upgrade, provision of logistics and equipment to support teaching and learning, enactment of enabling Acts of Parliament, etc.”

- “The education sector unions and associations: GNAT, NAGRAT, CCT, CHASS, CODE, APTI, were all roped in.”

- “The development partners – the World Bank, USAID, FCDO, (DfiD then), JAICA, etc., who are our key partners, were deeply involved right from the conception stage of our journey.”

- “I equally engaged a good number of the civil society organizations in education, as well as those whose activities relate indirectly to education, were engaged.”

- “As a strategy, I arranged for the leadership of the key stakeholders, such as the education unions, to meet and interact with the President on his vision for education and his national development agenda generally. These engagements helped a lot to ease the various agitations that were mounting.”

- “Put the head of the union in the cabinet for them to understand that indeed this was government priority Number 1, and the whole cabinet was behind it, including the President, 100%.”

- “The media was not left out. Beyond the periodic press conferences that were held to brief the media on the ministry’s activities. I tasked my deputies and agency heads to engage in frequent media programmes to inform and educate the public on the various reforms.”

A core reason Ghana’s Free SHS program succeeded was the deliberate strategy to map, engage, and coordinate stakeholders across every level of the education system.

This mapping was not just symbolic; each group was given a role in decision-making and communication. For example:

- Teachers’ unions brought representatives into program committees.

- School leaders (headmasters and headmistresses) participated through their associations.

- Parents and the media became partners in public updates.

- Retired educators and eminent experts formed advisory circles to shape vision and gather buy-in.

Professor Opoku-Amankwa added that “whatever vision was crafted became a shared vision. People were given various responsibilities, so it wasn’t just a government program, it became a national commitment.”

This approach also neutralized opposition and improved trust:

“We updated the public as frequently as we could. And with the unions involved, we had a seamless start.”

By mapping and activating 26 agencies under the Ministry of Education and multiple external groups, the GES and Ministry created a delivery network that could overcome skepticism, handle crises, and sustain the program beyond one government. Professor Opoku-Amankwa says:

“There wasn’t a single person who worked in the ministry who didn’t have something to contribute. Even the security person at the gate was expected to know the basics about the program.”

Political Navigation

Like in many countries, there was a strong political opposition in Ghana, and the opposition was intense. From Minister Prempeh’s perspective, “The opposition wanted to win the next election. They refused to support anything, held press conferences, and asked, ‘Where will students sleep? What will they eat? Where will you find the money?’ They even used my predecessor’s handover notes to highlight every gap.”

Infrastructure deficit was one of the pronounced challenges of the education sector in general, at the time the New Patriotic Party (NPP) took over the reins of government in January 2017. The opposition, then, the National Democratic Congress (NDC), argued that Ghana was not ready yet for the free SHS, insisting that free SHS could not be started because there was a huge infrastructure deficit that needed to be resolved first. But then, President Akufo-Addo and his government asked a simple question:

“Whose child should be left behind, while we build infrastructure to catch up?”

Minister Prempeh’s strategy was to out-communicate. “We met unions, parents, civil society, the press, anyone who would listen. We shared data, corrected misinformation, and gave regular updates. Because we had engaged early, people saw through the politics. By creating shared ownership, this goal gained legitimacy and avoided internal resistance.”

A key philosophy in Minister Prempeh’s leadership, according to Professor Opoku-Amankwa, was making sure every person in the ministry and every stakeholder could represent this program, even at the front gate of the Ministry. This ensured consistent messaging and built pride and ownership throughout the system.

In Minister Prempeh’s words:

“Criticisms were inevitable and were to be expected for such a grandiose pro-poor social intervention programme in a cash-strapped developing country such as Ghana. We were, however, resolved to execute the President’s vision of free SHS at all costs. We used the media more to educate and inform the general public on the importance of free secondary education. Perhaps we held more press briefings than any other ministry at the time.”

And delivery depended on trust and collaboration across diverse groups:

“Everybody who is a stakeholder was contacted, and they were represented in all the decisions that we made… teachers’ unions, heads of schools, parents’ associations, the media, and even retired professors and educators. Whatever vision was crafted became a shared vision,” Professor Opoku-Amankwa says.

By creating shared ownership, the program gained legitimacy and avoided internal and external resistance.

Delivering a nationwide program like Free SHS required more than plans, it demanded a mindset that treated every challenge as an opportunity to innovate, especially while dealing with multiple stakeholders. Professor Opoku-Amankwa described how a problem-solving culture, driven by the Minister and embraced by the entire team, became a cornerstone of their success:

“Anytime there was an issue, we discussed and found solutions. What he [minister Prempeh] was very much interested in was options… we would look at the strengths and limitations of each alternative before taking it to Cabinet for approval.”

This proactive, options-driven approach allowed the team to adapt quickly, whether it was managing unexpected over-enrollment through the double-track system or keeping education alive during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic via Wi-Fi, remote teaching, and carefully managed schools reopening.

Ultimately, political leadership was decisive. “The President drove this himself. He didn’t just sign off; he chose the Free SHS package, defended it publicly, and ensured funding. Without that will, it would have failed,” Minister Prempeh recalls.

Key Levers: Infrastructure and Teachers’ Capacity

In Minister Prempeh’s words:

“The first thing I did was to put a team together to do a study to apprise me with the state of education in the country. This included a thorough infrastructure audit for the entire education sector, however, with emphasis on SHS. The handing over notes of the then outgoing Minister for Education, Professor Jane Naana Opoku Agyemang (current Vice President of Ghana), also listed a litany of infrastructure challenges.”

“On the basis of the audit report, I worked closely with the Ghana Education Trust Fund (GETFund) and other fund sources from our development partners, to construct over 800 senior high school infrastructural projects between 2017 and 2021, covering:”

- 200 classroom blocks

- 200 new dormitories

- 350 science and computer laboratories were either newly built, retooled, reequipped or refurbished, and provided with requisite chemicals for practical work

- Construction of TVET workshops and school administration blocks

- 60 assembly halls, as well as dining halls, toilet facilities and teachers’ bungalows

“We equally provided furniture: bunk beds, classroom desks, laboratory equipment for all the newly constructed structures, as well as procured additional furniture for almost all the senior high schools. We also made provision in the free SHS budget for maintenance of buildings, furniture and equipment.”

“We also provided numerous resources and incentives to support teaching and learning:”

- Math and Science training for SHS teachers

- Core Textbooks: English language, mathematics, general science and social studies, for all SHS students

- Special annual training for teachers in the four Core Subjects:

- English

- Mathematics

- Science

- Social Studies

- Paid Teacher Motivation/Academic Intervention allowance to teachers

- Remedial packages delivered to all students

- Support for low-performing schools

- On-time payment of subventions

“Our strategy was not on rural schools per se; the strategy was to look up for underperforming schools. The MOE, GES, and the development partners – the World Bank, under the ‘secondary education improvement project’ (SEIP) had identified about 30% of our secondary schools across the country as underperforming. The SEIP supported the schools with infrastructure, grants, and training in accountability for heads and programmes for teachers to improve teaching and learning.”

Resource Mobilization

The cost of Free SHS was around 450–500 million US dollars annually for subsidies, textbooks, feeding, and teacher incentives, plus hundreds of millions more for infrastructure.

Funding strategies included:

- Allocating 9% of Ghana’s oil revenues to education.

- Securitizing the GETFund, Ghana’s education fund, for infrastructure.

- Leveraging World Bank and development partner support.

These resources funded 200 dormitories, 200 classroom blocks, 350 science labs, 600 assembly halls, new furniture, textbooks, and teacher pay raises of up to 80%, alongside extra allowances for tutoring students who needed tutoring. Minister Prempeh explains that:

“The government made funding available from the oil proceeds. About 9 percent of the country’s oil proceeds were earmarked for free SHS and the education sector. However, to secure funds upfront, the Ministry of Finance accepted my proposal to securitize the Ghana Education Trust Fund (GETFUND) receivables to secure the Ghana cedi equivalent of USD 1,500,000,000. This move helped to raise funds to support infrastructure development and the provision of tools and equipment for the sector.”

Moreover, implementing Free SHS required significant financial, human, and institutional resources, often in the face of skepticism, even within government. In Professor Opoku-Amankwa’s words:

“Even within the Government, we had initial challenges. There were ministers, including the finance minister at that time, who thought that we were probably rushing. There were times that we had a feeling we were being denied the resources to run the place.”

Despite this, the Minister for Education found ways to secure the necessary support, Professor Opoku-Amankwa shared. “He found a way of going around to get the right resources to move the entire programme.”

Resource mobilization went beyond just budget allocations. The team activated multiple ministries and agencies to contribute:

- Ministry of Health for school health programs and food safety.

- Ministry of Agriculture to secure food supplies.

- Engineers and infrastructure teams to expand school capacity.

- ICT investments, including Wi-Fi installations, to sustain learning during COVID-19.

This whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach ensured the Free SHS program had the financial backing, facilities, human capital, and technical support it needed, even when resources were scarce or contested.

Organizing for Effective Delivery

As Director General of the Ghana Education Service (GES), overseeing over 350,000 teachers and staff and more than 6 million students, Professor Opoku-Amankwa described how effective organization was central to the success of Ghana’s Free SHS. “My duty was to ensure the seamless and successful implementation of any program or policy that the Minister and the Government put in place. I was almost like a co-pilot to the Minister as far as the implementation of the free SHS was concerned,” he says.

Professor Opoku-Amankwa coordinated a vast network of Regional Directorates, Directors, District officials, and School heads. He emphasized the importance of clear roles and communication. “We had about 700 secondary schools across the country. Regional Directorates, Regional directors, District directors, and then the Heads of the schools. All that structure had to be aligned.”

This structure allowed the GES to act as the implementing engine for policies, while the Ministry handled strategy and policymaking.

Minister Prempeh also credits the Harvard Ministerial Leadership Program for sharpening his approach to his role. After his appointment in February 2017, he was invited to the Harvard Ministerial Leadership Program in June 2017, where he participated in the Sectoral Ministers Forum to go through the Program curriculum and access its resources. Minister Prempeh took full advantage of the opportunity, and as he put it:

“Harvard opened my eyes to delivery units, stakeholder mapping, and rapid implementation. It showed me how to track every detail, so nothing slipped through. That’s how we launched Free SHS in just seven months. My participation in the Harvard Ministerial Leadership Program gave me top notched knowledge and skills in leadership, governance and management. I got the opportunity to hear and learn at first hand the success stories and the pitfalls to avoid from a wide range of current and former ministers from across the globe. The Program also provided a network and a pool of experts to contact in times of need. Overall, the Program gave me the needed confidence to execute my mandate as Minister for Education successfully.”

Moreover, Minister Prempeh credits his knowledge in project management for leading with clarity and organizing for effective delivery. He says:

“Planning, preparation, communication and teamwork, and various leadership principles and stories, and case studies from my Harvard Ministerial programme, came in handy. The ‘traffic light system’ helped me a lot to monitor and track progress of work.”

Results: Launched Free SHS

Free SHS outcomes validated the effort. Impact was measured not only by implementation milestones, but also by student outcomes:

“When the first Free SHS cohort wrote their exams in 2020, 411 of our students scored top ‘A’ grade in all 8 subjects, out of 465 in all of West Africa. Ghana won all top three positions of the 2020 and 2023, won second and third positions in 2021, and in 2022, won the first and second positions of the West African Examinations Council’s International Excellence Awards.”

The positive outcomes have also reflected in the academic performance of the first four cohorts of the Free SHS who completed in 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023. Analyses conducted on performance trends in the core subject areas over a nine-year period, shown that the WASSCE results of the Free SHS 2020, 2021 and 2023 cohorts, scored above 50% in all four core subject areas, making their prospects for enrolment into tertiary institutions higher than in previous years.

TABLE 4: PERCENTAGE OF CANDIDATES OBTAINING A1 – C6 IN THE CORE SUBJECTS

| SUBJECTS | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English Language | 45.2% | 51.6% | 52.24% | 46.79% | 49.06% | 57.34% | 54.08% | 60.39% | 73.11% |

| Mathematics | 32.4% | 33.1% | 41.66% | 38.15% | 64.23% | 65.71% | 54.11% | 61.39% | 62.23% |

| Integrated Science | 28.7% | 48.3% | 52.89% | 50.48% | 62.94% | 52.53% | 65.70% | 62.45% | 66.82% |

| Social Studies | 57.4% | 54.5% | 42.52% | 73.25% | 75.36% | 64.31% | 66.03% | 71.51% | 76.76% |

Specific to the implementation of the Free SHS and the passage of the following two Acts were very significant: the Education Regulatory Bodies Act, 2020 (Act 1023) strengthened and enhanced the regulatory roles of the National Teaching Council, the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment, and the National Schools Inspectorate Agency. The Pre-Tertiary Education Act, 2020 (Act 1049), on the other hand, established the Ghana TVET service as a new agency to cater for the TVET sector. The Act also defined FSHS to include TVET.

In Professor Opoku-Amankwa’s words:

“Dr. Matthew Opoku Prempeh provided what I will call results-oriented leadership. He ensured that every team member had the resources required to enable them to deliver. He delegated effectively, monitored and did formative and summative evaluation of the programme. He devised what he called the traffic light system to effectively track implementation and the performance of each team member. Chaired meetings and gave support and guidance to the team.”

And because of the focus on this transformative goal and the strategic approach, Minister Prempeh says, “In the first year of Free SHS, dropout rates in the South fell to match the North. Over 100,000 students each year, who would have been on the streets were now in school.”

References

1 Borgen Project. “Ghanaian Government Supports Free Education Program – the Borgen Project.” The Borgen Project, 5 Oct. 2017, borgenproject.org/free-education-program/.