Chilean President Michelle Bachelet arrived in her office in Santiago early on Monday morning. She was preparing for her afternoon meeting with the Presidential Advisory Commission and senior colleagues at the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Finance.

To-date, Chile has two separate and unequal health care financing and provision systems, established by the Pinochet regime in the 1970s and 80s. President Michelle Bachelet, who took office in March 2014, convened a Presidential Advisory Commission to propose how to resolve the divide between the two sub-systems of public and private healthcare financing and delivery that have been in place in Chile for the last 30 years. The previous Presidential Commissions formed prior to 2014 were unable to find consensus on a health reform for the country. President Bachelet hopes to lead a health sector reform as part of her Presidential legacy.

As President Bachelet prepared for her afternoon meeting, she decided to review some historical facts about the health sector in Chile one more time, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of the public-private partnership in financing health care. Lastly, she is considering the two alternative health reforms voted for by the Presidential Commission.

What would you consider as the advantages and disadvantages of the Chilean model? What lessons do you learn for guiding your decisions about public and private partnership in financing healthcare?

Introduction

Chile, a high-income country in South America, has a population of 17 million people who enjoy an average GDP per person of $21,030 (ppp int $) (2014). Chile’s income is unequally distributed with a high Gini Coefficient of 0.51 in 2011 (1) with the average income of the richest quintile being 17.5 times higher than that of the poorest quintile and the richest 20 percent earning 58 percent of GDP (2). Chile has an under-five mortality rate of 8 per 1,000 live births and a maternal mortality rate of 22 (2013), health outcomes better than the average of upper middle income Latin American nations. Its national Total Health Expenditure (THE) was 7.4 percent of GDP in 2013 with 54 percent coming from private sources (3).

In the 1950s, the Chilean democratic Government established a national health service similar to the UK’s National Health System (NHS) model. The Government budget funded public health services to assure every citizen had basic health services. The Chilean health care system emphasized prevention and treatment of communicable diseases and maternal and child health services (4). However, the underfunding of this public scheme in addition to the rigid bureaucratic management of public health services resulted in long waiting times, inefficiency and poor quality of services. The Pinochet regime, an authoritarian military regime which took over the Chilean Government in 1973, decided to address the existing problems via a market approach for public and private health insurance. The Pinochet regime shared an ideology with the Chicago boys, a group of Latin American economists who studied or identified with neoliberal economic theories taught at the University of Chicago and advocated for a small Government, individual choice, private property and ownership, private market and minimum taxes.

1 The case was prepared under the guidance of William Hsiao. Cristian A. Herrera provided some of the data and prepared the first draft, Maria Joachim wrote the case and Ricardo Bitran reviewed and commented on the case.

As a result, the military regime continued to provide universal free primary health care with Government financing but it turned to a two-tiered approach for ambulatory and hospital services, thus giving rise to two different subsystems for health financing. Chile today relies on social health insurance (SHI) with two plans, the public plan (FONASA) covering about 78 percent of the population and private insurance plan (ISAPREs) covering about 17 percent of the population to provide nearly universal health coverage to its 17 million people (5).

Historical Development

The National Health Fund and the Private Health Prevision Institutions (1979 – 1990)

As a result of the ideologies of the Pinochet regime, Chile has had two public and private subsystems for over 30 years. As designed by the Pinochet regime, the public subsystem consisted of the large public insurer known as FONASA (Fondo Nacional de Salud, or National Health Fund). FONASA insured the majority of the Chilean population, including the indigent, low- and middle-income citizens and retirees. It covered primary and hospital health care delivered mostly through public providers while also offering a voucher system to subsidize general and specialty ambulatory care with private providers. The Government at the time also tried to improve the quality of public services by decentralizing Primary Health Centers (PHCs) from the central Government to municipalities. Financing for PHC was provided mostly by the central Government but municipalities were encouraged to contribute more, thus enhancing financing contributions to improve the quality of care for the Chilean population.

Despite decentralization to improve efficiency and quality, the Chilean public health services were still characterized by low levels of efficiency and quality. At the time, the Government also considered the introduction of modern management tools for public hospitals but little was done to implement such reforms. Hospital health workers’ unions were politically strong and opposed hospital management reforms. Given the political ideology of the Pinochet regime, which advocated deregulation and privatization, several insurers known as ISAPREs (Instituciones de Salud Previsional, or Health Prevision Institutions), were chosen as the alternative financing option to the public FONASA. ISAPREs, established in 1981, were for-profit private insurers that covered a small minority of the more affluent population (about 5 percent of the Chilean population) and provided services almost exclusively in the private sector (5). It is worth noting that in the 2000s, the Government attempted to suggest public management reform for the public sub-system once more but again, without much success.

In 1979, when the Pinochet regime decided to establish private insurance financing, the public FONASA was funded by a 4 percent of wages from formal sector workers in order to supplement the national Government’s health budget to pay for services provided by public health providers. In 1981, a parallel private insurance market was set up by allowing this tax of 4 percent to be transferred to the private ISAPREs. The first impact of the ISAPREs on public health services was the migration of higher income employees to ISAPREs. After the creation of the ISAPREs, hundreds of individuals started opting out of the public FONASA and directing their mandatory 4 percent health tax to ISAPREs. That movement created a financing gap for FONASA which had to be covered by the Ministry of Finance. To achieve universal coverage, Chile requires, by law, that all formal sector workers enrol in either FONASA or ISAPREs. ISAPREs have been allowed to charge an additional premium to their affiliates on the basis of an individually health risk condition and coverage of catastrophic health expenses. It should be highlighted that Chile gives individuals a choice for health insurance enrollment; those who are able and willing to pay the additional ISAPREs premiums can opt out of the public FONASA. At its inception, the Government provided an additional subsidy equal to 2 percent of the salary to those workers who wanted to join an ISAPRE so they can obtain the type of benefits they want. Other individuals, such as informal sector workers may choose to buy insurance from ISAPREs or FONASA. FONASA accepts any person regardless of their employment status or income. Unemployed and indigent individuals have the right to free coverage by FONASA.

The second impact of ISAPREs has been the more recent phenomenon of migration of physicians to the private sector (see below).

While the mandatory payroll health tax was set initially at 4 percent, ISAPREs pushed for an increase and after a few years, the contribution was increased to 7 percent, a percentage (up to a monthly salary ceiling of US$2,700), which still holds valid today for both FONASA and ISAPREs. The Government transfers the 7 percent payroll tax to ISAPREs for affiliates who enrol in it. In addition to the 7 percent contribution required by all FONASA and ISAPREs beneficiaries, ISAPREs, on average, charges an extra 3 percent of wages as additional premium to cover other benefits such as individual health risk, and catastrophic coverage. Catastrophic expenses under FONASA are covered in the standard contribution of 7 percent.

With regards to benefit packages, FONASA beneficiaries have had to make small copayments for ambulatory and inpatient services provided in public hospitals while ISAPRE beneficiaries have been required to make higher co-payments in public hospitals (6). FONASA covers and fully subsidizes indigent families. FONASA has also implemented a voucher system to cover a part of the cost of private care for its non-indigent beneficiaries. ISAPREs purchases most health services from private providers that are allowed to freely open facilities with only some minor sanitary regulations.

The Current Structure (1990s – present)

Chile returned to democracy in 1990 after a plebiscite that voted out Pinochet’s military regime. The new Governments were inspired by Christian humanism and social democrat ideas, pushing for reforms to correct the previous inequitable policies and weak regulation of the private sector. First, the State eliminated the additional 2 percent subsidies for enrollment in ISAPREs. Second, the Superintendence of ISAPREs was created to regulate the private insurance and the private provider markets. Third, in the early 2000s, the Government advocated for a significant health reform that created the Regime of Explicit Guaranties in Health known as AUGE (Acceso Universal con Garantias Explicitas), covering preventive and curative services for 80 prioritized health conditions (representing around 80 percent of the health burden). AUGE mandated SHI insurers to adopt the package via explicit legal guarantees for all beneficiaries as a tool to break the divide in the two-tiered health system. The AUGE law now governs the entire Chilean SHI system and applies to the indigent and the nonindigent members of FONASA as well as the higher-income beneficiaries of ISAPREs. The AUGE package guarantees not only treatments, but also sets upper limits on waiting times and Out-Of-Pocket (OOP) payments for treatments (7).

The Public-Private Health Financing Scheme: Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages of Private Insurers in the Health Financing Scheme

- Shared Government Budget

The FONASA per capita expenditure includes the 7 percent mandatory health contribution plus public subsidies that Government makes to FONASA which currently represents about two-thirds of FONASA’s budget. Real expenditure per capita for FONASA enrollees has increased from US$300 (2002) to US$508 (2011). The ISAPREs per capita expenditure figures include both the 7 percent mandatory health contribution and the additional voluntary contribution which averages another 3 percent points. Real expenditure per capita for ISAPREs enrollees has increased from US$720 (2002) to US$832 (2011). While ISAPREs’ per capita spending remains higher than FONASA’s, the gap between the two has been decreasing over time (5). It is worth noting that ISAPREs reached their peak coverage in 1995, covering about 26 percent of the population. Since then, ISAPREs coverage dropped; this can be explained by improvements in FONASA and the AUGE reforms which have been making FONASA a relatively more attractive option for the Chilean population.

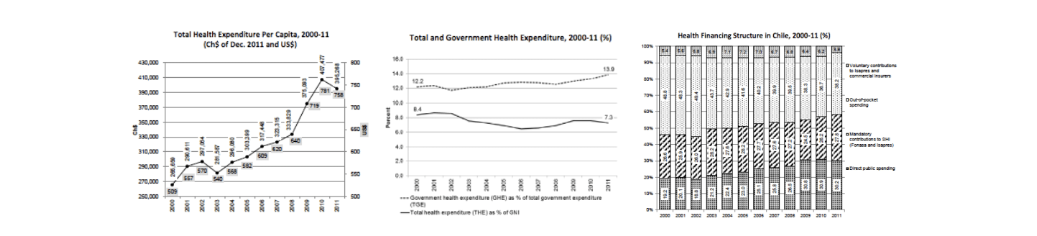

The Chilean Government has been spenting a larger share of its budget for health, growing from 12.2 percent in 2000 to 13.9 percent in 2011. The AUGE reform has been accompanied by a sizable increase in total health spending in the country, both from public and private sources. In absolute, real terms, THE per capita has grown by 48 percent, from 2000 to 2011. Nevertheless, with the rapid economic growth, The Total Health Expenditure (THE) of Chile has fallen as a share of GDP from 8.4 percent in 2000 to 7.3 percent in 2011. It is worth noting that despite insurance coverage from both FONASA and ISAPREs, the large source of health financing for Chile is OOP spending. OOP spending amounts to to 38.2 percent of THE (7).

Source: Bitran R. 2013. UNICO Studies Series 21 Explicit Health Guarantees for Chileans: The AUGE Benefits Package. The World Bank, Washington DC (7).

- User Satisfaction with Services and Perception of Protection

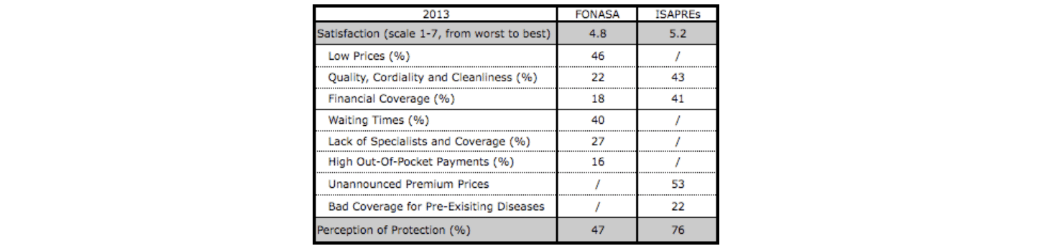

No systematic evaluation of health outcomes is available for FONASA and ISAPREs. However, we present a comparison of patients’ rating of their satisfaction with FONASA and ISAPREs on a few dimensions where data is available. There is no data on the difference in their clinical quality (8).

Source: Table constructed by case authors based on information provided in: Estudio de opinión a usuarios del sistema de salud, reforma y posicionamiento de la Superintendencia de Salud. Enero 2014, Superintendencia de Salud (8).

• Infrastructure, Technologies and Human Resources Investment

An impact of ISAPREs has been the more recent phenomenon of migration of physicians to the private sector, where they have better working opportunities and higher incomes. The Government has responded to this challenge by increasing the salaries of public physicians but to a level that is still less tan the private sector. The Government has also removed the requirement of having to pass a national medical board test to practice medicine in order to attract foreign physicians from Ecuador, Spain, Cuba, Spain, and other countries into the public health care system.

Furthermore, ISAPREs have been instrumental in boosting private investment for health. There is almost no regulation on private providers investing in new medical technology. Competition between public and private providers propelled new investments in the major cities for new private hospitals and accelerated the introduction of new medical technologies. By 2012, private sector owned 22.4 percent of hospital beds in Chile with an increase of 24 percent of private for-profit beds between 2005 and 2012 (9).

- Catastrophic Expenditure Coverage

By regulation, every ISAPRE plan must include coverage for catastrophic diseases (known as CAEC by its Spanish acronym) in its benefit package, funded by the 3 percent additional premium. CAEC requires the beneficiaries to pay a deductible of US$4,800 for each disease suffered. FONASA also covers the catastrophic expenses, but without charging additional premium. Despite the establishment of CAEC, patient financial protection is a concern for beneficiaries of both FONASA and ISAPREs. While the establishment of CAEC provides additional financial protection, Bitran and Munoz have shown that the incidence of catastrophic expenditure for Chilean households does not depend on income or insurance schemes, indicating that neither FONASA nor ISAPREs adequately addresses the problem of providing financial protection against catastrophic health expenditures (10).

It is worth nothing that 25 percent of patients covered by ISAPRES receive services in public facilities because they cannot afford the ISAPREs co-payments (11, 12) while almost half of all catastrophic events among children of ISAPRES members are treated in public hospitals (13).

In recent years, comercial insurance to cover catastraphic expenses has grown rapidly, purchased by 4.6 million people. The majority of the purchasers are reported to be the middle- and upper-income individuals covered by an ISAPRE who seek further financial protection through private insurance (7).

Disadvantages of Having Private Insurers in the Chilean Health Financing Scheme

- Disparity by Income and Risk Selection

First, the public-private insurance system is segmented by income, with the majority of low-and middle-income groups enrolled in the public FONASA; 79 percent of the population is covered by the public system. There is neither risk pooling nor income re-distribution between the sub-systems—FONASA and ISAPREs—thus segregating the rich and the poor. As the ISAPREs affiliates also pay premiums on top of the mandatory 7 percent of their wages (thus a total of about 10 percent of their wages), ISAPREs receive 54 percent of all the total revenues for the social insurance schemes to provide coverage only to 16.5 percent of the Chilean population (14).

Second, ISAPREs segment their market by charging an additional premium according to individual health risks. To assess the individual risk, ISAPREs attempt to predict the future health expenditure for each person and charge the premium accordingly. Consequently, less healthy people and women in childbearing age have to pay significantly higher premiums to buy or continue enroll in an ISAPRE plan. As a result, the great majority of the less healthy people are covered by FONASA. In addition, the proportion of people over 60 years is significantly higher in FONASA than in ISAPREs.

Third, the pre-existence of diseases constitutes a major challenge for ISAPREs beneficiaries. Those with pre-existing conditions or for reasons of age or gender have a limited ability to shift its enrollment to another ISAPRE plan. As a result, 39 percent of all ISAPREs affiliates are ‘captive’ because if they change to another ISAPRE, they might not be able to afford the new required premium (14). Furthermore, the pre-existence of diseases does not allow affiliates with chronic conditions to switch from FONASA to any ISAPREs plan as they wish. The Government is not willing to compensate ISAPREs for the actuarial risk of FONASA beneficiaries that decide to migrate to an ISAPRE.

- Imperfect Insurer-Provider Relationship in the Private Sector

First, vast majority of the private services were paid by fee-for-service (FFS). Under FFS, providers induce demand so they can earn higher income and jeopardizes cost containment and efficiency. Moreover, the fees paid by ISAPREs to private providers are defined on a free market basis, separately from the public sector, where standard Government-defined tariffs are listed for all services provided by public facilities. Consequently, payment rates are much higher in the private sector. In addition more resources and better infrastructure are available in the private sector, therefore attracting physicians and nurses with higher wages and leaving the public sector understaffed.

- Increasing Number of Judicial Accusations Against ISAPREs

ISAPREs have witnessed an exponential growth in the number of lawsuits from their affiliates due to changes in premium prices. 60 percent of the cases processed by the Appellation Courts are related with ISAPREs (14, 15).

- Deregulation of Complementary and Supplementary Insurance

ISAPREs can be considered as both complementary (covering services beyond the basic coverage offered by FONASA) and supplementary (covering some services that are not included in FONASA’s basic coverage). ISAPREs are able to provide these plans because they get the mandatory contribution and extra premiums, thus collecting about 10 percent of the richest wages in Chile.

Current Health Financing Reform Options under Discussion in Chile

The current health system in Chile requires reform: risks are not pooled, members are charged premiums according to their health conditions and are unable to switch between ISAPREs because of pre-existing conditions while the private insurers issue their own rules and set their annual premiums without transparency. After President Michelle Bachelet took office in March 2014, she convened the Third Presidential Advisory Commission for Health Reform. Along with her leadership, the delegation of Commissioners voted on medium- and long-term health reform alternatives: a National Health Insurance System and a Social Health Insurance. Similar to the First and Second Commissions, the Third Commission under Bachelet’s leadership did not deliver a consensus report but contrary to the two previous Commissions, it did achieve majority and minority views for health financing reform.

The Minority View: Social Health Insurance System (SHI)

The minority view supports keeping the two-tiered health system now in place but solving some of the aforementioned problems of ISAPREs. Under the SHI model, collection of financial resources relies on the labor market; payroll taxes can be deducted from worker’s wages and companies’ taxes with State subsidies as contributions.

The “minority” position is to preserve the current system of competition among insurers but to solve the problem of captivity in ISAPREs by setting up a Risk Equalization Fund (REF) fund among them as a means to adjust risk and make it illegal for ISAPREs to reject clients based on age, gender and health status. In addition, the minority position seeks to make ISAPRE plans more transparent and to require all ISAPREs to offer the same benefits package, known as Guaranteed Health Plan (GHP), while allowing them to sell complementary insurance above the GHP. The contents of the GHP would largely exceed the contents of AUGE. In fact, the GHP would contain AUGE, plus catastrophic coverage, plus coverage for preventive care, plus coverage for all non-AUGE services (7). Further, each ISAPRE would offer this plan at a single price for all beneficiaries irrespective of their age, gender, or health status.

The Majority View: National Health Insurance System (NHI)

The majority view supports a single payer, single public insurer instead of keeping the SHI currently in place. In this alternative, collection of funds would be the same as for SHI, with contributions from workers, enterprises and the State. In addition, the resources collected would be pooled in a single fund that would be managed by a public autonomous entity.

The main difference between the two suggested models would be on the purchasing side. The NHI model would be a public single-payer system that would purchase services for the entire population, based on a single benefit package guaranteed for all. The management of the single-payer would have a participatory board with representation of public and private actors (including users) related with the system. On the side of providers, the existence of public and private facilities would be maintained, but the Government would regulate the contractual relations and payment rates, thus stimulating more coordinated networks of care. Co-payments would be regulated and made homogeneous and proportional to the income of the affiliate and with a stop-loss mechanism to avoid impoverishment due to health expenditures. Through this scheme, ISAPREs could be transformed into complementary and/or supplementary health insurers that would be supervised by the Superintendence of Health.

References

- World Bank Statistics. 2015. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/?display=default. Accessed on March 12th 2015.

- CASEN. Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, La Encuesta de Caracterización Socioeconómica Nacional, Casen, 2013.

- World Health Organization. 2013. “Chile: Health Profile.” Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/countries/chl.pdf?ua=1

- Molina C. 2006. “Antecedentes del Servicio Nacional de Salud. Historia de Debates y Contradicciones. Chile: 1932-1952.” Cuadernos Médico Sociales (Chile), 46(4): 284-304.

- Bitran R. April 21, 2015. “The Public-Private Health Financing System in Chile: Winds of Reform.” Ministerial Leadership In Health. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

- Jimenez J & Bossert T. 1995. “Chile’s health sector reform: lessons from four reform periods.” Health Policy, 32: 155-166.

- Bitran R. 2013. UNICO Studies Series 21. “Explicit Health Guarantees for Chileans: The AUGE Benefits Package.” The World Bank, Washington DC.

- Superintendencia de Salud. Enero 2014. Estudio de opinión a usuarios del sistema de salud, reforma y posicionamiento de la Superintendencia de Salud.

- Asociación de Clínicas de Chile. Diciembre 2013. “Dimensionamiento del sector de salud privado en Chile. Actualización a cifras del año 2012.”

- Bitran R, Muñoz R. 2012. “Chapter 6: Health Financing and Household Health Expenditure in Chile”, in Knaul FM, Wong R, Arreola-Ornelas H. “Household Spending and Impoverishment.” Volume 1 of Financing Health in Latin America Series. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Global Equity Initiative, in collaboration with Mexican Health Foundation and International Development Research Centre, 2012; distributed by Harvard University Press. Available at: http://www.idrc.ca/EN/Documents/Financing-Health-in-Latin-America-Volume-1.pdf

- Annick M. 2002. “The Chilean health system: 20 years of reforms.” Salud Publica Mex 44: 60–68.

- Larrañaga O. 1997. “Eficiencia y equidad en el sistema de salud chileno.” CEPAL 49: 1–45.

- World Bank. 2000. “Chile health insurance issues: old age and catastrophic health costs.”

- Comisión Asesora Presidencial para el Estudio y Propuesta de un Nuevo Marco Jurídico para el Sistema Privado de Salud. Informe Estudio y Propuesta de un Nuevo Marco Jurídico para el Sistema Privado de Salud. October 8th 2014. Available at: http://web.minsal.cl/comision_asesora_presidencial. Accessed on March 14th 2015.

- Miranda M, Sandoval G, Núñez D. 2014 (August 30). “Recursos contra alzas de precio en planes de Isapres llegan a 16 de las 17 cortes del país.” La Tercera. Available at: http://www.latercera.com/noticia/nacional/2014/08/680-593625-9-recursos-contra-alzasde-precio-en-planes-de-isapres-llegan-a-16-de-las-17.shtml. Accessed on March 13th 2015.