Introduction

From 2002 to 2010, Colombia underwent an Educational Reform under the leadership of Minister of Education Cecilia María Vélez White, which strived to develop a more efficient system to ensure education access for all through tackling local union power and interests with firm and decisive actions (MinEducación, 2010).11 This set the foundation for profound changes that to date have resulted in increased access to educational services from early childhood (reaching 646,188 children with comprehensive attention by 2009) to higher education (63% increase from 2002 to 2009). The number of students in pre-school, primary, and middle school rose from 9,994,404 in 2002 to 11,241,474 in 2009; quality improved in K-12 where dropout rates decreased from 8% in 2002 to 5.4% in 2008 and tertiary education certification increased with the number of graduate students graduating with masters degrees growing (6,776 in 2002 to 16,317 in 2008). In addition, the reform almost tripled the number of doctorate students from 350 to 1,532 in the same period; and led to the creation of information systems for improved data collection and problem solving. As with any large-scale transformation, a number of factors had to align to create a conducive environment.

Such was the case of Colombia during the two-term presidency of Álvaro Uribe Vélez, where the intentional political and operational strategy of the administration involved many confluent stakeholders aiming together for the same objectives. It is through this lens that this case study will examine Colombia’s education revolution with the ultimate goal of highlighting actionable strategies that current ministers can employ to facilitate their own institutional change.

Legislative Environment: Tools for a Reform

To understand the success of the Educational Revolution in Colombia, one first needs to analyze the process that began a few years prior to actual policy implementation. In the early 2000s, Colombia was living through a period of great instability caused on the one hand, by an ongoing armed conflict that had eroded its social tissue and blurred the lines of the State, and on the other hand of the biggest financial crises in its recent history. With a rapidly increasing deficit, Colombia had to commit to more efficient use of the nation’s budget. As a result of these contextual factors, President Andrés Pastrana introduced two key pieces of legislation in 2002, the last year of his administration, that laid the groundwork for Colombia’s Educational Revolution.

The first piece of legislation (Law 715) modified a previously instated decentralization process that changed the way resources were allocated. It “unified the budgetary allocation and the contributions to the national government’s revenue in a General Contribution System (SGP)” (MinEduación, 2010)11 and shifted many attributions that had previously been conferred to the territories back to the national government. One of the consequences of these decentralization laws was that the implementation of educational policies was now the mandate of local Secretaries of Education. In cities where the population was greater than 100,000 citizens, new administrations were created with more ascriptions. The administration of education in rural areas also shifted from the national government and became the responsibility of the now enhanced local Secretaries of Education.

To help the President tackle the surrounding crisis, Congress authorized for extraordinary legislative powers to be attributed to the President to transform the educator’s career path. This led to the second big legislative change which had to do with the teachers’ promotion system. Previously, teacher salary raises were determined only by seniority (rather than by merit) and with increasing seniority each year, the system had become unpayable and urgent change was needed. Two different options were considered to deal with the salary situation: (1) the possibility of reforming a teaching statute seemed unlikely to find consensus among the union leaders, educator, education specialists, and the government due to the short time available, or (2) the introduction of a statute that would only be applied to new teachers entering the workforce with entrance exams and evaluation for promotion. A fast negotiation with a fragmented Teacher Union, which had internal problems due to unstable leadership and to the fact that many of its representatives in Congress were not grouped in a single front, but rather in several political parties, that doubted that the government would be able to move forward with a new proposal concluded with the introduction of a new and controversial teaching statute, the 1278 Presidential Decree (MinEducación, 2010).11

Political Context: 2002 Presidential Campaign & Selection of Minister of Education

Concurrent with these legislative changes, Colombia was in the midst of a presidential campaign. At the time, both the business community and civil society were strong proponents of the idea that education should be a central piece of a Colombia that was forward looking. Colombia’s constitution mandated that the political platform and proposal of any presidential candidate that was elected became the basis for the national strategic plan. Knowing this, some representatives of the business community and civil society organized a series of dialogues and encounters with all presidential candidates in which they talked about their vision for the education sector moving forward. It was clear that stability was crucial, since the average term in office of a Minister of Education in Colombia had historically been only seven months. During these encounters, representatives from the sectors conveyed to all candidates that for a meaningful change in the education sector to take place, it was necessary for them to name a Minister that would stay in their position for the full length of the administration.

The presidential campaign saw the rise of a local politician whom many perceived as an outsider: Álvaro Uribe Vélez. He had won his nomination as an independent candidate without the formal support of a political party, and a strong stance against the FARC (Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces). Uribe promised the business community and civil society that if he won, he would only name one Minister of Education for the full length of his administration. He ultimately won the presidency with over 53% of the vote and his allies won Congress in a landslide.

With presidential victory in hand, Uribe began his search for the ideal person to become the next Minister of Education. Cecilia María Vélez White emerged as the natural candidate. Minister Vélez had majored in Economics at the Louvain University in Belgium and pursued graduate studies in urbanization at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Her experience at the Central Bank, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the National Planning Department provided her with insights into both public administration and finances.

Vélez was a well-respected name in the sector due to the profound change she had achieved as Secretary of Education in Bogotá (1998 – 2002) during the government of Mayor Enrique Peñalosa, which continued with Mayor Antanas Mockus. During her time as Secretary, her team had been at the forefront of the decentralization process from a local administration perspective and had the opportunity to “pilot” some of the changes she would later implement at a national scale. She was able to create information systems to more accurately collect data on student enrollment, teacher attendance, and infrastructure tracking. She used this data to track school performance, identify infrastructure needs, and adjust teacher pay based on absenteeism. The results of her ministry’s interventions could be clearly seen in non-profit public education providers that operated in highly marginalized neighborhoods, known as Concession Schools. These schools saw improvements not only in standardized test scores but also in process indicators such as parent participation and school punctuality, which could be easily contrasted with those of nearby public schools who did not receive the same interventions.

In her role as Secretary, Vélez acquired an insightful perspective into the education sector and learned some of the strategies to negotiate with different stakeholders. Her management style and professionalism helped her consolidate a high-quality technical team that would continue with her throughout the years as Minister.

Given her track record of success in both leadership and implementation, President Uribe invited Vélez to become Minister of Education. While the emphasis of President Uribe’s administration was security and stabilizing the country, he was still a strong proponent of Minister Vélez and her education reform efforts for two reasons. Firstly, he was trying to regain spaces where the presence of the State had been lost and basic services had been impossible to provide due to the armed conflict. Secondly, his own management style was similar to that of Minister Vélez and thus they were able to work together easily. Thus, Minister Vélez began her term backed by a President with a very high approval rating who also had the cooperation of the majority of local authorities. This gave her significant political capital which eased the future implementation of the reform.

Leadership: Decisive Actions to Set Course

Minister Vélez came into her position with clear knowledge of the education sector and a vision to transform it. She knew she had to aspire to an ambitious set of goals that comprehensively shifted every aspect of the sector so she created a strategic plan with three main goals: to increase access, to improve quality, and to modernize institutions with the use of information systems. These goals were chosen to promote a robust system with higher standards to ensure a developed, egalitarian, and peaceful Colombia. The first period’s goal was to emphasize education as a social government policy with a strong focus on equality, and the second period would set the education policy as a cornerstone of competitiveness for the country (MinEducación, 2010).11 But to start, she first needed to “put the house in order” in her ministry.

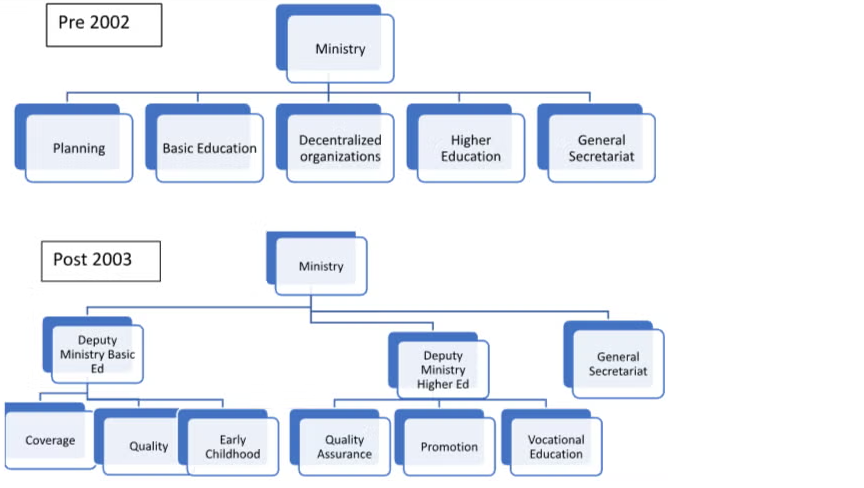

Minister Vélez and her team started doing this by reorganizing the structure of the ministry (Annex 1). The new organizational structure was based on functions and was meant to be supported by reliable information systems. To uplift morale and generate buy-in to this change, Minister Vélez focused on tangible, physical changes to the ministry as well. First, she turned a dated, bare-bones office environment with minimal technology into an open co-working space with more furniture and better use of space. Second, she instituted a “customer service system” [Sistema de Atención al Ciudadano – (SAC)] on the first floor of the ministry, which consisted of a one-stop shop for citizens to get help with accessing any Ministry services and provide feedback.

As the space changed physically, so did the culture of the Ministry. First, Minister Vélez recruited a strong technical team with significant expertise. She led by example to demonstrate the kind of work ethic she expected of her team. She was a strict leader who always came in at 7 a.m. and stayed in the office until the job of the day was done but she also wanted to show investment in her employees so she supported workforce training programs to improve capacity in digital literacy, results-based management, and other technical functions that could foster effectiveness and efficiency. Minister Vélez and her team were able to promote buy-in from all ministry employees through open and transparent communication and by creating channels and routines for direct communication with her. The first Monday of every month, she held a planning meeting with the most senior ministry officials: vice ministers, the secretary general, and ICFES1 and ICETEX2 directors. Every subsequent Monday of the month, she would open the meeting to first include directors from different areas for budgeting and planning; then to include deputy directors to follow up on project implementation; and finally the last Monday of each month would be an open conversation conference for all employees to share and discuss policy ideas.

Finally, Minister Vélez prioritized improved organization of data and use of information systems within the ministry. This started with better organizing archived information and ensuring systems were in place to appropriately store and use routinely collected data (Annex 2). It also included making sure this data was publicly available to ensure accountability to all stakeholders.

While many of these moves consolidated the efforts of previous administrations to modernize the sector, they also caused tension between the educators in the ministry who called for pedagogical accompaniment and felt that the focus on modernization was overlooking other critical areas in need of reform.

1 The ICFES underwent also an important change from being the “Colombian Institute for the Promotion of Higher Education” to becoming the Institute in charge of Assessing and Evaluating all levels of Colombia’s education.

2 Colombian Institute for Educational Loans and Technical Studies Abroad (Instituto Colombiano de Crédito Educativo y Estudios Técnicos en el Exterior, “ICETEX”).

Implementation: Collaboration, Data, & Communication as Tools for Success

When leading an institution such as the Ministry of Education one has to manage a number of different stakeholders both internally (e.g. ministry, Cabinet, President) and externally (e.g. local secretaries of education, teachers, unions, the business community, parents, students, etc.). Thus, a Minister’s scope of action to implement change is heavily impacted by her ability to dialogue and negotiate with different stakeholders and to convey well-tailored messages to address their varied concerns.

A key factor contributing to Minister Vélez’s success was her ability to coordinate and collaborate with the wide range of interests that surrounded the education sector. She was able to do this well because she ensured that she had access to timely data on which to support her decision making and communication. This evidence-based strategy allowed her to more effectively disprove misconceptions and provide accurate information where needed. In addition, and perhaps more importantly, it allowed her to acknowledge accurate faults identified by any of the stakeholders, so that she could also set a timeframe to respond to them and show indicators of progress.

Local Secretaries of Education

One of the most difficult challenges to overcome when working at the federal level was coordination with local entities. The decentralization process that Colombia was undergoing exacerbated some of these difficulties as local authorities had varying levels of capacity to deal with the new mandates for which they were now responsible. The Ministry of Education had to work closely with local authorities to make sure that education policies designed at the federal level could be implemented effectively. There were several mechanisms for this cooperation. The first one echoed the way in which the Ministry had achieved internal buy-in: communication. Every three months, summits were introduced and almost all the newly appointed education secretaries convened to discuss and learn about the changes that were being promoted at the Ministry. These summits also gave them the opportunity to share best practices from the federal level and across local levels, and to ask for the institutional help they needed in order to transform local capacity.

Even though the success with which the local authorities were able to implement the educational revolution was uneven (mainly because it also depended on the size and wealth of each of the departments and municipalities), there were incentives promoted by the ministry that supported a good degree of implementation. For instance, Law 715 not only changed the formula for the distribution of resources to the regions, but it also attached them to the number of students enrolled in each school. This was a fundamental transformation of the incentives and logic with which local authorities functioned; now they were forced to increase enrollment to get more resources. This policy of “money following the students”, plus a policy designed by Minister Vélez and her team to distribute additional resources to areas where the vulnerable populations were, helped promote the access in an unforeseen manner. It also created a new problem: “phantom students,” which gave the ministry additional incentives to create, promote and audit accurate information systems. To address this unintended consequence, the ministry had to confront the data systems it had with data from other governmental agencies and an auditing system implemented with the ICFES.

Higher Education Institutions

Legislation preceding Minister Vélez’s term had near autonomy of higher education institutions. This had led to a large increase in access to higher education (from 22% of the total students who graduated from high schools enrolling into tertiary education in 1992 to 46% in 2002) but was not accompanied by any oversight to ensure quality. To satisfy the need for more regulatory control and standardization, one component of Minister Vélez’s reorganization of the Ministry of Education was the introduction of the Vice Ministry for Higher Education.

This change was important because it elevated the importance of higher education to the vice-ministry level and institutionalized a state policy process into the creation of a National Accreditation Board composed of universities representatives. This allowed for important and constant dialogue coordinated by the Ministry between the presidents of private and public universities, professors, the business community, and student unions to co-create and define the standards and certifications that would govern them. Stakeholders felt heard in this process, and their feedback was documented in the ECAES3 series, where both positive, those who view it as an opportunity to add structure and to redesign their programs, and negative reviews, especially regarding fear of losing autonomy and more government incidence, from university presidents can be read. Universities were incentivized to participate in this change from a low regulatory environment to a strict, but voluntary, accreditation process because of the appeal and prestige associated with the government certification that would be granted to programs that were deemed to be high quality. The certification process sparked competition among public and private institutions, thereby creating a higher quality and better-regulated system in a short period of time.

3 Examen de Estado de la Calidad de la Educación Superior (State Exam for Higher Education Quality), which was later renamed SABER – PRO and is administered by the ICFES.

Colombian Educators Foundation (FECODE) Union

FECODE is Colombia’s largest teachers’ union and it has traditionally served not only to protect the labor rights of teachers in the country but also to contribute to education policy. Minister Vélez’s administration is still the only that can claim that during her eight years in office there was not a single general strike. Alongside a mutual understanding to place teachers’ wellbeing at the heart of policies that govern them, four main reasons contributed to such an atypical relationship between Vélez’s ministry and FECODE.

Firstly, as with other stakeholders, Minister Vélez ensured open and regular communication routines with FECODE with a clearly defined agenda centered on teachers’ wellbeing and working conditions. She instituted monthly meetings between herself, her senior ministry team, and the leaders of FECODE. In this meeting, she would share updates from the ministry on policy and implementation progress and listen to suggestions and complaints from the union. The Minister appointed her General Secretary to monitor the agreements that were reached in these meetings and to keep all parties updated on progress. This process allowed for constant advancement in the union’s efforts to protect teacher rights and was seen as a win for both sides.

Secondly, before taking office Minister Vélez negotiated with President Uribe that one of the requirements for her to become Minister was that the teacher payroll had to be up to date and disbursed on time. Since FECODE’s main goal is to ensure the labor security of its members, the fact that the Ministry was delivering salaries on schedule created a strong foundation for a fruitful and stable relationship.

Thirdly, Minister Vélez was in a politically fortunate situation. Her predecessors had recently passed laws instituting an admissions process to become a teacher and a merit-based teacher evaluation system. Despite regional resistance to some of these laws, Minister Vélez was legally mandated to implement them and she was able to communicate these constraints effectively to justify her actions. Building on this, while it was often customary for politicians to ally themselves with FECODE during elections and then remain indebted during their administrations, Minister Vélez and President Uribe were not constrained as such. Thus, they could always remain firm and maintain their independence when dealing with FECODE. However, this never translated into active opposition because Minister Vélez and her team understood that teachers’ wellbeing is a critical element of a successful education sector.

Business Community

The business community played a prominent role in the reform by serving as key allies throughout the process. Building on President Uribe’s initial promise to protect the Minister of Education protection during his term, the business community had created a key source of stability for Minister Vélez which gave her the opportunity to promote large scale changes. During her time in office, local chambers of commerce and regional companies provided significant donations which suggested that the government was working alongside the business community, something that was unusual in Colombia at the time. To the general population, this was perceived as an endorsement of the ministry from a serious enterprise.

To maintain this support, Minister Vélez arranged monthly meetings with some of Colombia’s most important industry leaders and “Empresarios por la Educación” [Businesspeople for Education]. These meetings provided a space for accountability and an opportunity to solicit advice regarding the professionalization of a sector badly in need of capacity development among its workforce. The advice from these meetings ultimately led to the ministry obtaining technical support from a firm that specialized in organizational change and helped reinforce the actions pursued by the ministry.

Media

As she demonstrated with all stakeholders, Minister Vélez’ ministry was one that was open for dialogue and the profound transformations made the education sector a newsworthy topic that the media was eager to cover. The ministry was willing to communicate with the media and used it as an avenue to showcase its progress since this was the first time that the Ministry of Education had quality, publicly available data. The increased accessibility of information about the education sector meant that public interest increased. The Ministry faced a more informed population which scrutinized their actions and ultimately, created a higher level of accountability in the public sphere.

Outcomes: Successes and Outstanding Challenges

As a result of the changes implemented in Colombia’s Education Reform, there were significant improvements in access, quality, and information systems as mentioned earlier. Below are some additional highlights achieved during this period:

- Literacy: Between 2002 and 2008, 1,017,934 adults learned how to read and write.

- Higher Education: The number of instructors increased by 32.6% between 2002 and 2008, and their professionalization can be measured thanks to an increase in instructors with graduate degrees of 46% and those with doctorate degrees grew 87.2% in the same period. Dropout was also considerably reduced from 16.5% in 2002 to 12.1% in 2008.

- Infrastructure: To control and improve the education inventory funds were tied to the improvement and regularization of the infrastructure. As a result, between 2003 and 2008 1,760 educational institutions had projects approved, which meant an increase in project approval from only 7% in 2002 to 27.2% in 2008.

- Private education: Thanks to efforts in certifying and assessing the private institutions, the number of schools that were labeled as Regulated Freedom (i.e. certified, accredited or high-performing schools) rose from 33% in 2006 to 42% in 2009, and those labeled as Controlled Operation (i.e. sanctioned or low-performing schools) decreased from 31% in 2006 to 20% in 2009

- Teacher Training: For the first time in Colombia’s history, teachers were able to enter the workforce after passing an evaluation. Between 2002 and 2008, 49,727 teachers and teacher directors were hired through competition (16%) and 14,265 teachers and teacher directors took the promotion evaluation.

Despite the significant progress Minister Vélez was able to accomplish, certain challenges persist in the education sector. Firstly, even though the center of her quality strategy was to set standards and implement student evaluations, some actors claim that pedagogy has not changed at the classroom level and that memorization and rote learning is still a common pedagogical method at the school level. Even though some teacher training programs were implemented to improve instruction, limited federal and local resources prevented the distribution of textbooks to all schools, forcing learners to rely on public libraries. Such an example highlights the stark inequalities that remain between the private and public schools.

Another ongoing challenge is the proposed transformation of the teacher admission process. Even teachers who went through this process (i.e. passed an entrance exam and underwent one year of training) were not necessarily appropriately trained to teach. Teaching manuals were provided to all teachers but workshop training to supplement them did not occur. As such, the admissions process did not improve teaching quality and demand for teachers meant that schools were not able to be as selective as they would like in their hiring.

Lessons Learned: Recommendations for a Minister of Education

Colombia’s experience during the Educational Revolution helps to highlight the importance of a strong Minister of Education in creating a clear vision and taking decisive actions. The ambitious goals that were outlined since the presidential campaign thanks to dialogue with key stakeholders were constantly co-constructed at different levels. The public had access to this progress thanks to transparency in the education indicators and the promotion of public discussions.

Transformation of a sector cannot be a one-person job, so the importance of working alongside a strong team is vital for any leader’s success. In Minister Vélez’s case, she was able to summon a team of well-respected professionals in the education sector, who were themselves insiders with technical knowledge. Their competence was found not only in the highest offices, but also at middle management levels to lead each of the workstreams. The leaders of Colombia’s educational policy today emanated from this time. Perhaps, the inclusion of more geographically diverse team could have helped to point out solutions to some of the problems the implementation encountered.

Another important factor was that as a coordinating agent of the educational sector, Minister Vélez invited local authorities to assess the policies and their implementation. Their presence and participation helped tailored the national policies to local realities that they knew from first-hand experience. This two-way communication was possible because of the ability to listen, learn, and act with humility when people perceived certain actions as mistakes. The fact that Minister Vélez was also willing to walk alongside her teams in the territories also created a sense of proximity that allowed her to put a face to the stories she was telling with precise data and accurate information systems. She was able to steer the public conversation away from general strikes and into more constructive nuances, which created a better-informed society that held the ministry, local authorities, and school staff accountable. The alliances formed with civil society, the media, and the business community were also a central factor for the buy-in the Educational Revolution had from the public.

Her ability to align herself with the agenda of the President, and to count on his support, gave Minister Vélez the stability that was needed in the sector to stay on as minister for eight years, making her the second longest-lasting minister in the recent history of Latin America. Education policy is a long-term project, so being able to think and implement policies throughout two administrations allowed the sector to understand and cope with the changes gradually, but most importantly, to see the results of each of the actions that were being put into place.

Another fundamental lesson was that, thanks to her prior knowledge of the sector acquired while serving as Secretary of Education in Bogota, she was able to think about the sector comprehensively. This also allowed her to come up with a National Strategic Plan that shaped the guidelines and goals of her administration since the very first days. Instead of promoting incremental changes in small areas, she pursued an ambitious transformation of the sector as a whole.

The above was only possible because of the information systems that were installed. Up to date information was able to be conveyed from the territories to the ministry and back to detect problems and to act upon them. The coordination mechanisms that supervised and audited the information served to decide on agreements and to fix short- and long-term measurable goals that were monitored by dash-boards. This allowed for a periodic assessment of progress that disentangled the complexities of tackling the system as a whole.

At the time, two issues in Colombia had been spared from the ideological struggles between the left and the right: urban policy and education. Both were areas where a consensus was possible and where “soft reformism” was given fertile ground to promote better services for the overall population resembling an effective social democracy. Although many of the actions performed by Minister Vélez and her team were well known around the world, the way in which she implemented them made a big difference in the outcomes when compared to other cases in the region. Her example shows that with an understanding the importance of the human factor combined with data-based decisions, real change is possible, even in a context as challenging as the education systems in Latin America.

This report was made possible by the Harvard Ministerial Leadership Program. None of the conclusions, recommendations, and/or opinions expressed in this report necessarily reflect those of the Harvard Ministerial Leadership Program or Harvard University and its affiliates. © 2019 Harvard Ministerial Leadership Program.

References

- Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. (1997). Reframing Organizations, Artistry, Choice, and Leadership, 6th Edition, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, Inc.

- Davis, I. (2010). “Letter to a newly appointed CEO,” in McKinsey Quarterly, McKinsey Company.

- Deal, T. (1985), “Cultural Change: Opportunity, Silent Killer; or Metamorphosis?” in R. Kilmann, M. Saxton, R. Serpa, Gaining Control of the Corporate Culture, San Francisco: Jossey- Bass. pp. 292-331.

- Delors, J. (1998). Learning: The treasure within. Unesco.

- Reimers, F. (2019). Cartas para un Ministro de Educación. Cambridge.

- Hauser, C. B. (2015). A Communication Strategy for the First Six Months in “Opportunity Knocking.”, Council for Advancement and Support of Education

- Hackman, J. R. (1998) “Why Teams Don’t Work,” Leader to Leader, Winter. P. 24-31.

- Kingdon, J. W., & Thurber, J. A. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies (Vol. 45, pp. 165-169). Boston: Little, Brown.

- Kline, H. F. (1999). State building and conflict resolution in Colombia, 1986-1994. University Alabama Press.

- McLaughlin, J. (1993) “Leadership Transitions: A Wide-Angle Lens,” in Harvard Institutes for Higher Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Education, vol. 2, no. 2.

- Ministry of Education (MinEducación) of Colombia. (2010) “Colombian Educational Revolution 2002-2010. Action and lessons”. Ministerio de Educación de Colombia 2010.

- Mintzberg, Henry, and Frances Westley. (1992). “Cycles of organizational change.” Strategic management journal 13, no. S2: 39-59.

- Orlando Melo, J. (2017). Historia mínima de Colombia. El Colegio de Mexico AC.

- Vélez, C. (2019). Building Institutional Capacity for Large Scale Educational Reform [ppt Slides]. Shared from lecture on March 2019 at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Annex 1: Re-Engineering of the Ministry

Source: Vélez, C. (2019). Building Institutional Capacity for Large Scale Educational Reform [ppt Slides]. Shared from lecture on March 2019 at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Annex 2: Information Systems

Source: Vélez, C. (2019). Building Institutional Capacity for Large Scale Educational Reform [ppt Slides]. Shared from lecture on March 2019 at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Methodology: Interviews

The interviews were conducted in person or virtually and consisted of 20-minute to two-hour in-depth conversations about the role and perceptions of these stakeholders who played a central role in Colombia’s Education Reform.

| Persona | Cargo 2002 – 2010 |

|---|---|

| 1 Alberto Espinosa |

Founder and member of Business People for Education |

| 2 Angela Constanza Jerez Trujillo |

Communications Coordinator of the Alliance, Education Commitment of All |

| 3 Anibal Gaviria |

Former Antioquía Governor |

| 4 Cecilia María Vélez White |

Former Minister of Education of Colombia, Former Secretary of Education of Bogota |

| 5 Daniel Bogoya |

Former ICFES Director |

| 6 Fabio Sánchez |

Professor Los Andes University (School of Economics) |

| 7 Felipe Barrera Osorio |

Professor HGSE & World Bank |

| 8 Gabriel Burgos Mantilla |

Viceminister of Higher Education |

| 9 Himelda Martinez |

Viceminister of K – 12 |

| 10 Isabel Segovia |

Viceminister of K – 12 // Former Vice-president Candidate |

| 11 Javier Botero Álvarez |

Viceminister of Higher Education |

| 12 Jorge Enrique Giraldo |

Founder and member of Business People for Education |

| 13 Jorge Orlando Melo |

Historian and editor of the “Memorias de la Revolución Educativa” [Memories of the Educational Revolution] |

| 14 Juan Pabo Caicedo |

Chief of Staff of the Minister of the Interior – HKS |

| 15 Juana Inés Díaz Tafur |

Viceminister of K – 12 |

| 16 Margarita Peña Borrero |

Former ICFES Director |

| 17 María Figueroa |

Seating ICFES Director |

| 18 Maria Juliana Rojas |

Specialist in K-12 at HGSE |

| 19 Nohemy Arias |

Secretary General of the Ministry of Education |

| 20 Pablo Correa |

El Espectador / Journalist and analyst |

| 21 Pablo Navas |

President of Los Andes University |

| 22 Roxana Segovia de Cabrales |

Secretary of Education of Cartagena y Viceminister of K – 12 |

| 23 Senén Niño |

President of FECODE 2008 – 2013 (Teacher Union) |

| 24 Sonia Perilla |

El Tiempo / Journalist |

| 25 Stephanie Majerowicz |

PhD HKS – Education Policy |