Introduction and Overview

Policymakers can use investments in health and health systems to create value in two distinct but related ways: by generating “value for money” and “value for many”.1 Value for money refers to the relative magnitude of a positive output or outcome relative to the size of investment, typically measured using cost effectiveness tools, whereas value for many refers to the distribution and equity of the outcome among the population. Thus, government officials must carefully consider how to prioritize budgets in order to generate the most value, defined broadly, in their country.

The total size and allocation of a budget for health expenditures can have direct and indirect impacts on population health.2,3 Indeed, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with similar Gross Domestic Product (GDP) levels, similar health expenditures as a proportion of GDP, and similar per person expenditure levels on health have highly varying health outcomes on a number of dimensions, including life expectancy, infant mortality, maternal mortality, and availability of treatment for diseases such as HIV and diabetes.4

In addition, investing in health also brings distinct economic benefits for the country5–10 and political benefits for the policymakers who choose to prioritize health. Microeconomic evidence suggests that healthy development of children allows for increased income later in life and general health of adults has positive impacts on their income. At the macroeconomic level, health of the population can lead to growth in the country’s economy through increased labor productivity, increased incentives for individuals to invest their incomes due to longer life expectancy, and a “demographic dividend.” With regards to the political implications of allocating resources for health, health is a major concern among the public in countries of all income levels, including low-income countries.11 Cases from Turkey, Brazil, and the UK demonstrate that government prioritization of health investments can have a positive impact for governing parties that commit to investing in and strengthening health systems.

This document provides an overview of four key questions that policymakers can consider when determining how to generate the most value through health budget priority-setting:

- What values underlie the government’s priorities for the country?

- Based on these values, what goals for the healthcare system does the government hope to achieve?

- Based on these goals, where should the government allocate its financial resources for health?

- How should the government allocate its financial resources for health?

We will first address these questions and then consider the potential health, economic, and political consequences of various health budget allocation decisions.

What Values Underlie the Government’s Priorities for the Country?

Although a broad range of values can drive the government’s approach to resource allocation, these value sets generally fall into three broad categories: utilitarian, liberal, and communitarian.5

Utilitarians are consequentialists and focus on the value, or utility, that a policy or other decision will have. Using a consequence-based approach to decision-making, utilitarians generally believe “the ends justify the means” (assuming “the means” involve ethical and legal decisions). Policy analysis tools such as cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analysis reflect utilitarian concerns of generating the greatest outcome for the greatest number of people using the fewest possible resources. Of course, predictive uncertainty about the total utility that a policy will generate causes difficulty for utilitarians. Further, utilitarians differ in how they would choose to measure total utility. Subjective utilitarians argue that value is subjective to the individual and that individuals must judge their own happiness for themselves. Accordingly, subjective utilitarians might measure the total utility of a product or service using the price that a person would willingly pay for it. In contrast, objective utilitarians argue that individual’s choices are not always rational or valid and that an objective index of well-being is better suited to measure utility. Such indices include Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) and Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs), which are composite indices combining number of years lived as a result of an intervention (adjusted for disability or quality of those years lived); health economists employ these measures in cost effectiveness analyses in order to compare and argue for certain policies over others. Some might describe pure utilitarianism as “ruthless” in that it can justify excluding certain populations who would cost too much to treat (e.g. rural populations without easy access to a medical facility). Hence, equity is not the primary concern of utilitarians, who are more likely to prioritize efficiency and effectiveness.

Liberals take a rights-based approach to allocation of health resources. Liberals believe that all humans have the capacity and obligation to display mutual respect to each other, and this mutual respect endows individuals with rights, or “claims that all individuals can make on each other by virtue of their humanity.” Some liberals, known as libertarians, focus only on negative rights, which guarantee individual freedom. For example, libertarians might focus on the rights of the individual to choose their physician. In contrast, egalitarian liberals also emphasize the importance of positive rights, or a minimum level of resources and services, which can guarantee the ability for an individual to exercise his or her free choices. Accordingly, egalitarian liberals tend to favor redistribution of resources in order to ensure that the entire population has access to basic positive rights. However, with regards to prioritizing health, egalitarian liberals differ in their views on whether individuals have a right to health services (i.e. provision of and access to care) or health status (i.e. the achievement of general well-being).

In contrast to the first two value sets described, communitarians do not focus on the level of the individual in assessing a policy, but rather on the level of the community or society; in other words, they recognize the social nature of life in their assessment of policies. As such, communitarians evaluate the merit of a policy on whether it adheres to a community’s value set and whether it promotes individuals and a society consistent with that value set. Thus, communitarians would generally oppose a health policy which achieved positive population health outcomes with an intervention that defied local cultural norms or values. Communitarians fall into two broad categories: those who believe in a single set of values which would promote a better society (universal communitarians), and those who argue that each society should set its own values and norms based on the context-specific factors (relativist communitarians).

Before moving on to discuss how values could lead to different goals for the healthcare system, one should note that these value sets are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Policymakers might include both a utilitarian and communitarian perspective in an analysis where they prioritize health interventions based on their objective utility, but choose to exclude any that overtly defy local norms. Further, governments can modify their ethical values as they learn more about a population’s needs and their ability to meet those needs. However, it is important to maintain adequate “coherence and explicitness” when articulating one’s values; doing so creates transparency for the population and gives others the opportunity to agree with the government’s choices because they can understand the rationale behind these choices.

Based on These Values, What Goals for the Healthcare System Does the Government Hope to Achieve?

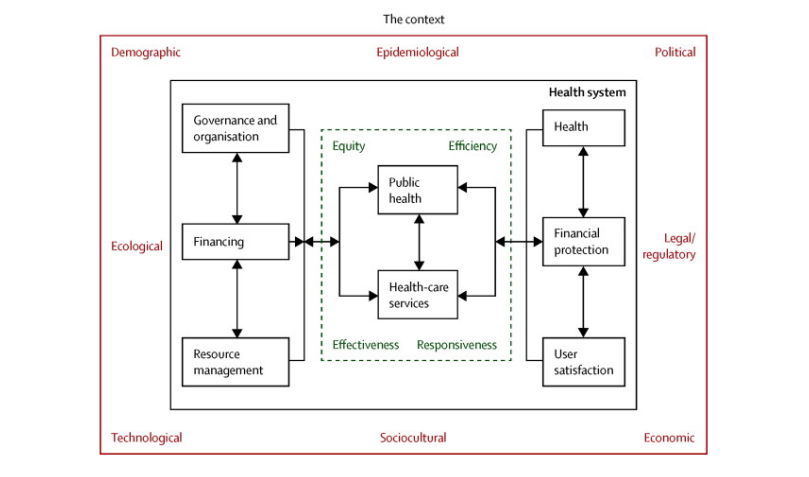

Policymakers must consider which outputs and outcomes to prioritize when allocating resources for health investments. In this context, the term outputs refers to how well the health system performs its delivery of personal and public health services to the population, whereas outcomes, also known as goals, refer to the ultimate ends that the health system aims to achieve. These goals include health status, financial protection, and user satisfaction. (See Figure 1 for an overview of a health system’s functions, objectives, outputs, and outcomes.) In many cases, strong delivery of health systems outputs is necessary but not sufficient for strong performance on health systems outcomes. Below we discuss how a policymaker might prioritize health systems outputs and outcomes, and how the three value sets described above might influence the balance of objectives a policy maker might have in relation to health system outputs and outcomes.

A policymaker needs to balance four key objectives for the outputs achieved by a health system: equity, efficiency, effectiveness, and responsiveness.12 The four objectives for health systems outputs are:

- Equity refers to the differences in how a policy affects people of different groups. The most common concern is equity among populations of different income groups in relation to access to health system outputs or in relation to health outcomes. Other equity issues, such as disparities between rural and urban populations, also should and often do inform policy. An analysis of a policy’s “vertical equity” takes into account its differential impact across populations at different income levels, whereas an analysis of “horizontal equity” looks at whether the policy treats individuals at the same income level the same.5

- Efficiency has been defined many ways in the fields of policy analysis. For the purposes of health systems analysis, we define efficiency using the concept of technical efficiency, drawn from economics. Technical efficiency accounts for whether society is producing the most goods and services for the least cost.

- Effectiveness refers to whether interventions are evidence-based and safe.12 In other words, an effective intervention will achieve the desired health outcomes.

- Responsiveness refers to whether the health system meets the public’s legitimate nonmedical expectations. Responsiveness is a highly subjective measure and depends on the perceptions among citizens of a health system’s functioning.13

Without a doubt, policymakers’ values will influence which health system objectives they choose to prioritize for the health system outputs. For example, pure utilitarians will likely care most about efficiency and effectiveness, and they will less likely prioritize equity. They might also disregard the importance of responsiveness as an objective, unless they believe that a health system’s responsiveness generates value for the population. Liberals, who focus on individuals’ rights, will prioritize equity and responsiveness of the system, with libertarians emphasizing the importance of choice and egalitarian liberals emphasizing the equity in access to positive rights (e.g. basic health services and medicines). Communitarians, who emphasize society’s values, will prioritize the objectives most relevant for achieving the best possible society. Accordingly, they will likely emphasize responsiveness and equity of the system at a societal level.

In addition to setting objectives for health systems outputs, policymakers must also pay attention to the health systems outcomes, or the overall goals for a country’s health system. These fall broadly into three categories: population health status, financial risk protection, and citizen satisfaction.5,12

- Health status refers to the actual health of a population. Measurements of population health status include life expectancy, burden of disease, mortality rates for specific groups (e.g. infant mortality and maternal mortality), and prevalence of specific diseases.

- Financial risk protection refers to helping people avoid very large and unpredictable payments for health, sometimes known as catastrophic expenditures. Mechanisms to provide financial risk protection typically involve insurance schemes with risk-pooling functions. Measuring levels of financial risk protection can be difficult because a person having insurance coverage does not necessarily mean that they have coverage for a complete package of basic medicines and services. In addition, individuals may technically have insurance to cover medicines and services, but they may not actually have access to these services (e.g. due to geographic disparities, physician shortages, or drug stockouts), thereby rendering their insurance coverage of little value.

- Citizen satisfaction refers to the degree with which users of the health system rate the system as satisfactory. Citizen dissatisfaction with the health system can serve as a major catalyst for reform, as we will discuss later. Measuring citizen satisfaction typically involves conducting surveys with citizens and possibly evaluating their willingness to pay for services.

As with health systems outputs, health systems outcomes also derive directly from the value sets described earlier. For example, objective utilitarians might concern themselves most with the population’s average health status, whereas egalitarian liberals might focus most on the range of health status (as a measure of equity levels). Egalitarian liberals will also emphasize the importance of financial risk protection as a means for ensuring minimum economic opportunities for all. Subjective utilitarians might place a high value on citizen satisfaction, as would libertarians (in the sense that satisfaction relates to an individual’s level of choice.)

Based on These Goals, Where Should the Government Allocate Its Financial Resources for Health?

Once the government has identified its objectives for the outputs and outcomes of the health system, it can decide upon specific programs or interventions to achieve these goals and allocate budgets accordingly. In this section, we describe the decisions a government faces about where to allocate its resources. In the next section, we describe a process and framework for making these allocation decisions.

As shown in Figure 1, a health system has four main functions which a government can prioritize for investment to develop a well-functioning health system: governance and organization, health financing, resource management, and healthcare / public health services. Governments can also choose to invest in specific disease programmes or interventions, as discussed below.12

- Governance and organization encompasses the organizations and institutions involved in delivering products and services to citizens.14 The organization of the health system includes hospitals, primary care clinics, and supply chains which provide medicines to providers. A government could choose to invest in the governance and organization of the health system, for example, by updating management policies for health facilities, changing the referral network of the system, or improving processes for decision-making at the programmatic level.

- Health financing involves the provision of insurance plans to offer financial risk protection to citizens. Mechanisms for doing so include public insurance, social insurance, and community-based health insurance.3 A government could choose to invest in health financing by creating a new insurance scheme, expanding coverage of existing insurance to new patient populations, or by expanding the range of services covered under existing schemes.

- Resource management entails overseeing the inputs that go into the provision of health care, such as human resources and labor, pharmaceuticals, and medical technologies.14 The government can invest in the management of resources by purchasing these resources (e.g. through the procurement of drugs or hiring of doctors), or by improving systems that oversee resources (e.g. budgeting tools, health information systems) or that deliver them (e.g. through supply chain management systems).15

- Healthcare and public health services refers to all of the activities actually involved in delivering care to patients and which can be facilitated by strengthening health systems. These activities include doctor’s visits, surgeries, health education and training for citizens, and the distribution of relevant health-related products. Governments also invest in specific services that generate value for money and value for many – for example highly cost effective interventions that have population impact. These include health promotion to change risk behavior (for example to stop tobacco smoking, reduce alcohol intake, exercise, eat healthy food, undertake physical activity, practice safe sex, among others), prevention services (immunization, voluntary male circumcision, condom use, use of insecticide treated nets, for example), and treatment (such as antiretroviral treatment for HIV, treatment for tuberculosis, malaria, chronic illness – high blood pressure, heart disease or diabetes mellitus for example) and care.

Several investment frameworks have been developed to identify “good buys”, for example those identified by the Lancet Commission on Investing in Health16; UNAIDS HIV Investment Framework17; STOP TB Strategy18; the Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health spearheaded by the UN Secretary General19; interventions identified in the Global Malaria Action Plan20; and the Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease Interventions (also known as WHO-PEN).21

How Should the Government Allocate Its Financial Resources for Health?

Of course, when deciding where to allocate resources for health, policymakers face many questions. Some relate directly back to the question of equity. For example, one must consider whether policy interventions should target populations that are poor or middle-class, urban or rural, working-age or the young and elderly? Others relate to the effectiveness and efficiency of the system. Should the government prioritize investment in health systems, in expensive interventions which lead to guaranteed improvements in outcomes, or in less expensive intervention that have some risk of failing? With regards to responsiveness, policymakers might face a dilemma when they decide whether to implement an effective intervention that may conflict with local cultural norms and demands.

Unfortunately, there is no algorithmic formula for determining which health interventions or areas to prioritize, and limiting analyses to comparisons of cost-effectiveness is insufficient. Without universal consensus on principles for prioritization, governments need another approach to make allocations and justify their decisions.22 Accordingly, several ethicists have proposed a framework known as “accountability for reasonableness” (A4R) to guide this decision-making process. A4R is a process, grounded in democratic principles, which aims to legitimize decision-making among “ ‘fair-minded’ people who seek mutually justifiable terms of cooperation.”23

A4R has four key conditions, which we quote from Gruskin and Daniels (2008) below:

- Publicity condition: Decisions that establish priorities in meeting health needs and their rationales must be publicly accessible.

- Relevance condition: The rationales for priority-setting decisions should aim to provide a reasonable explanation of why the priorities selected were determined to be the best approach. Specifically, a rationale is reasonable if it appeals to evidence, reasons, and principles accepted as relevant by fair-minded people. Closely linked to this condition is the inclusion of a broad range of stakeholders in decision-making.

- Revision and appeals condition: There must be mechanisms for challenge and dispute and, more broadly, opportunities for revision and improvement of policies in light of new evidence or arguments.

- Regulative condition: There must be public regulation of the process to ensure that conditions 1, 2, and 3 are met.

One should note that A4R does not lay out priorities for government investments, but, rather, a process for publicly and legitimately determining these priorities in order to guide investment decisions. The principles of A4R have shaped priority setting for health in many places such as: UK, where the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) takes social value judgments into account when making recommendations about coverage for new treatments; Mexico, where decisions about which diseases the public catastrophic insurance should cover involve working groups that evaluate the clinical, economic, ethical, and social considerations; and Oregon where, in 2008, a Health Fund Board made a plan to insure all legal residents of the state involving a wide group of stakeholders and extremely transparent decision-making / information-sharing.

The Impact of Government Health Spending (GHS) on Health Outcomes

In the preceding sections, we have discussed the various frameworks policymakers can use to determine where to allocate resources, as well as a process for doing so. It is also instructive to examine the evidence for the potential implications of these investments. In this section, we discuss the implications of allocating resources for health on the health outcomes of the population. In the next sections, we discuss the implications of allocating resources for health on the economy and political landscape of a country.

Changes in government health spending (GHS) can have a direct impact on cause-specific mortality. For example, in low-income countries (LIC) a 1% decrease in GHS is associated with an increase of 18 deaths for every 100,000 live births in the neonatal period and 98 deaths before the age of five for every 100,000 live births.24 The statistical significance of this result held even when controlling for economic conditions, infrastructure, infectious disease rates, and private health spending rates. Similar results were found when only examining infant mortality in Africa and, with slightly less extreme results, for high-income countries (HIC).25 Globally, a 1% increase in GHS is also associated with a significant decrease in cerebrovascular deaths.24,26 And research among European Union countries has found that a 1% decrease in GHS is associated with increased maternal mortality.

Research coming out of IMF also suggests that increasing GHS and improving its efficiency can increase overall life expectancy in a country.9 For example, among African nations below the regional average for GHS, increasing GHS to the regional average would improve health adjusted life expectancy (HALE) by 1.2 years. In Asia / Pacific, this figure would improve by 0.9 years, and in Middle East / Central Asia, this figure would improve by 4.1 years. In addition, among African nations below the regional average for efficiency in GHS, increasing efficiency to the national average would result in an increase in HALE by 1.5 years. In Asia / Pacific, this figure is 1 year, and in Middle East / Central Asia, this figure is 1.3 years.

Achieving the health systems goal of financial risk protection through universal health coverage (UHC) can also improve population health status. Cross-country statistical evaluation of the influence of insurance coverage on health outcomes suggests that financial coverage has a causal influence on health, especially for low-income individuals, who gain better access to necessary care when they receive coverage.27 Examination of individual countries’ experiences implementing UHC supports this finding. For example, Thailand’s Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) included benefits such as inpatient and outpatient care, surgery, accident and emergency visits, dental care, diagnostics, prevention and health promotion, and medications, and UCS increased utilization of many health services, including inpatient and outpatient visits.28,29 UHC in Turkey improved access to maternal and child health services, resulting in a significant decrease in infant mortality, as well as an improved ratio of physicians-to-patients across the country.12

Similarly, across many Latin American countries, health has been established as a constitutional or legal right, and many countries have expanded primary care as part of a platform universal health coverage.30 This push for universal coverage has led to significant decreases in infant mortality, under-5 mortality, and maternal mortality across most Latin American countries between 1990 and 2010.

Finally, one should note that efficiency and effectiveness in treating specific sets of disease can change over time as medical technologies and approaches to care delivery shift.31 For example, treatments for cataracts and depression have shown increases in the productivity of care following a decrease in per-case treatment costs. In contrast, per-case treatment costs have increased for other complex treatments and procedures, such as those associated with childbirth, but the improved health outcomes associated with these costs make the investments worthwhile.

These data provide empirical evidence that governments can directly promote improved health outcomes for citizens through government health spending, but policymakers must allocate funds wisely in order to achieve their desired outcomes.

The Impact of Improved Health on the Economy

Evidence also suggests that improved population health has positive economic impacts for a country. Since, as we have already shown, GHS can have a positive impact on population health, one might argue that GHS has a “return on investment” in the form of stronger economic output for the country. Evidence for the linkage between health and increased economic output exists at both the microeconomic and macroeconomic level.

At the microeconomic level, better health can improve the financial prospects for individuals and households.6 In particular, malnutrition, frequent illness, and unstimulating home environments can limit the physical and cognitive development of a child. On the other hand, proper nutrition and health allows for the adequate physical development of children and improved performance in school. Thus, investments at an early age “help to raise the potential for long-term academic and workplace success and lifelong well-being.”6 Among working individuals, research using the cost-of-illness approach indicates that falling ill can have direct, negative consequences for their income. The mechanisms linking ill health to reduced income include decreased productivity at work, long-term separation from the work force, and disengagement from other economic activities. Interventions targeting specific diseases and conditions, such as deworming for school children, iron supplements and iodine to treat malnutrition, and malaria prevention can all lead to improved education or income outcomes for individuals.7

Macroeconomic evidence also supports the idea that investing in health generates positive economic returns.7 In particular, there are four channels through which investments in health might improve the overall economic state of a country, all of which are corroborated by the microeconomic evidence described above. First, ceteris paribus, a healthy workforce will have higher labor productivity than an unhealthy workforce due to increased energy and reduced illness-related absenteeism. Second, a healthy population has increased educational opportunities, and education levels have a direct impact on income growth for a country. Third, populations with high life expectancies will tend to save more for the future and likely will have more working years. These increased savings can lead to increased investable capital, an important driver of growth.

Fourth, health investments that change mortality rates and total fertility can lead to demographic shifts which benefit the economy through a mechanism known as the “demographic dividend.” Often, when a country experiences a sudden improvement in health (e.g. due to the introduction of a new set of vaccines), the total fertility rate remains high for a while, but the infant mortality rate declines rapidly. This dynamic leads to a “baby boom.” Eventually, fertility rates begin to decline as couples realize that more of their infants will survive, and the original baby boom cohort reaches working age. Thus, the ratio of working-age to non-working-age people in the country increases and productive capacity increases on a per capita basis. In other words, countries that experience this demographic shift have a greater percentage of the population contributing to the economic output at any given time. Assuming that the country has or can create certain conditions to enable productivity of this working-age group (e.g. proper educational opportunities), the country will experience a “demographic dividend” that leads to its growth. This demographic dividend accounts for up to one-third of the economic boom that many East Asian countries experienced between 1965 and 1990.

Expenditures on antiretroviral therapy (ARVs) for people living with HIV/AIDS provide a useful case study of a health investment with significant health and economic returns.32 By the end of 2011, 3.5 million patients were on ARVs co-financed by the Global Fund, and 80% of those patients lived in 20 African countries. The total cost of treating these patients from 2011 to 2020 is estimated at $14.2 billion. This health investment will save up to 18.5 million life-years. Further, it will yield up to $34 billion in economic benefits (for a net benefit of up to $19.8 billion) through three primary channels: $31.8 billion in labor productivity improvements, $0.83 billion in orphan care costs averted, and $1.4 billion from the delay of end-of-life care.32

The Impact of Health Investments on the Political Landscape

Without question, the process of formulating health policy and allocating resources to health depends on the political structure and climate of a country, and, as such, has implications for the country’s political outcomes. Although a complete analysis of the way that politics and health systems reform shape each other is beyond the scope our analysis is here, it is instructive to point out explicitly that the two do matter for each other.5 Political processes shape health sector reform, and health sector reform (or lack thereof) has direct and indirect consequences for politics and politicians. For example, the move towards universal health coverage (UHC) has had distinct positive political benefits in many countries over the last several decades.33 (Figure 2 provides an overview of programs implementing UHC and the reasons for doing so in various countries.) In this section, we consider three case studies where health policy had direct implications for the political process: Turkey, the UK, and Brazil.

Box 1: Turkey’s Health Transformation Program

In the 1990s, Turkey faced three distinct but related problems related to its health system: inadequate and inequitable financing of the system, an absolute shortage and inequitable distribution of physical infrastructure and human resources, and disparities in health outcomes, especially between the east and west.12 For example, under-5 mortality rates in 1998 were 75.9 deaths per 1000 live births in the less-developed east and 38.3 deaths per 1000 live births in the more developed west. In addition, a major earthquake in 1999 left 17,000 dead and another 500,000 homeless, thereby exposing major faults in the government’s ability to manage and deliver services.

Turkey’s 2002 elections resulted in a majority for the Justice and Development Party, ending a decade of ineffective coalition governments. In 2003, as part of a broader objective to improve the economy and the government’s functioning, the Ministry of Health (MoH) introduced a Health Transformation Program (HTP) to help achieve UHC. Motivation to enact these changes, including improvements in the health system, came directly from public pressure, and failing to achieve these goals would have resulted in significant public backlash.34 Further, the public expressed high levels of dissatisfaction with the health system, with only 39.5% of people indicating they were satisfied with quality of care in 2003. Accordingly, the government displayed high levels of political commitment to this effort, with the Minister of Health visiting 81 provinces at the beginning of the HTP to meet with local government and agree to HTP implementation plans.

The HTP aimed to address challenges in a number of areas, including organization, financing, service delivery, human resources, and pharmaceuticals. The government undertook implementation of HTP using a flexible approach, focusing first on incremental and tactical changes with high visibility to citizens and later on long-term, strategic shifts that required structural changes to the system. Implementers also continuously monitored the progress of the HTP; they placed a high emphasis on citizen satisfaction with the transition, conducting focus groups, stakeholder analyses, and annual household surveys. The HTP ultimately led to significantly improved access to and usage of health services, resulting in improved health outcomes on a number of important measures such as infant and maternal mortality. User satisfaction with quality of care also increased to 79.5% by 2011. Ultimately, the successful rollout of HTP served as a blueprint for the expansion of other social services by the Turkish government, and public satisfaction with the process contributed to the government’s re-election in subsequent years.

Brazil’s Health System Restructuring During Political Transition

In the decades leading up to the re-democratization of Brazil between 1985 and 1988, the military dictatorship had generally deprioritized the protection of social rights, including health, education, and adequate living conditions.35,36 In particular, the fragmented health system left large portions of the population without access to care. Against a backdrop of general discontent with the government, a funding crisis in the social security system motivated a “public health movement” that prioritized UHC and decentralization of health delivery. Health reforms to address the system’s issues began in the 1980s. They gained a strong legal basis when the 1988 constitution formally defined health as a “citizen’s right and obligation of the state” and established the Unified Health System (SUS), which sought to unify the fragmented care delivery network into a national health system under the purview of the MoH.35

In order to appease the private sector, who opposed the government overtaking all healthcare delivery activities and who already provided care for many who had social insurance, the government focused its strategy on primary care delivery. The main component of the primary care delivery system Family Health Strategy (FHS), which consists of “multidisciplinary teams of health professionals… responsible for a defined territory and population with whom they establish contact and share responsibility for health care.”35 FHS involved transfers of funding to the municipality level based on the total number of people each municipality served (which incentivized expansion of the program to cover more people), clear roles and responsibilities at different levels of government, and a robust monitoring and evaluation (M&E) system that supported continuous improvement. The government made results from this M&E system publicly available in order to promote transparency and accountability to the public. This strategy has served expanded deliver healthcare to the poor and to place an emphasis on preventative care, although many are still left behind. Today, 75% of Brazil’s population, or 195 million people, receive services and coverage from SUS.37

Today, Brazil is facing high levels of dissatisfaction once again. In the past two years, the public has staged protests against low GHS and a system which, once again, has become fragmented and somewhat unresponsive.37 In the 2014 general election, the incumbent President, Dilma Rousseff, was re-elected by a narrow margin despite this public dissatisfaction of government resources, and many attribute her successful re-election to her government’s focus on anti-poverty programs.38 She now has the challenge of fulfilling campaign promises to use increased government revenues to raise healthcare spending, with a particular focus on improving the quality and number of public hospitals and healthcare professionals.

Public Engagement with UK’s NHS

The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) provides an example of a health population deeply engaged in the political dimensions of health delivery.1 A proud establishment of the UK’s public sector, the NHS is generally ranked as a high-performing health system among high-income countries.39 Further, an overwhelming majority of the population supports the existence of the NHS and its founding principles, with 89% of the public agreeing with the idea of a tax-funded national health system which the government runs. In spite of this broad support, however, the NHS still faces a number of challenges with regards to user satisfaction and future directions. On the one hand, 65% of the population is satisfied with the care they receive, and only 28% of the public reports worsening standards of care among the NHS. At the same time, however, 51% of the public believes that the NHS “often wastes money,” and this figure exceeds 60% for individuals over age 48. Accordingly, 58% of the public would not support spending cuts to other public services in order to increase spending for the NHS. These perceptions vary by the level of engagement with NHS, with individuals who have received more care from the NHS having better views of the organization than those who have had less contact with the system.39

The high level of engagement among the public with the NHS, coupled with some perception issues, poses a challenge to the NHS, particularly as it faces a funding issues. Indeed, projections show that by 2030, the NHS will have a £65 billion funding gap. In addition, the NHS will face four key transitions that will force the government to rethink the structure and role of the NHS: a demographic transition to an older population, an epidemiologic transition to more chronic illness and multimorbidity, an economic transition with a widening income gap across the country, and a social transition to a public that places a high degree of value on responsiveness of the system and personalization of care. UK policymakers will have to balance the competing health, financial, and social demands placed on the NHS in order to maintain its relevance going forward.39

Figures

Figure 1. Health systems functions, outputs, and outcomes.

Figure 2. Representative list of reforms implementing universal health coverage.

| Country | Year | UHC Reform | Political timing / reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-income countries | |||

| UK | 1948 | Tax financed National Health Service with universal entitlement to services | Welfare state reforms of new government following Second World War |

| Japan | 1961 | Nationwide universal coverage reforms | Provide popular social benefits to the population |

| South Korea | 1977 | National health insurance launched | Flagship social policy of President Park Jung Hee |

| USA | 2012 | National health reforms designed to reduce number of people without health insurance | Major domestic social policy of the President |

| Low- and middle-income countries | |||

| Brazil | 1988 | Universal (tax-financed) health services | Quick-win social policy of new democratic government |

| South Africa | 1994 | Launch of free (tax-financed) services for pregnant women and children under six | Major social policy of incoming African National Congress Government |

| Thailand | 2001 | Universal coverage scheme extends coverage to the entire informal sector | Main plank of the populist platform of incoming government |

| Zambia | 2006 | Free health care for people in rural areas (extended to urban areas in 2009) | Presidential initiative in the run up to elections |

| Burundi | 2006 | Free health care for pregnant women and children | Presidential initiative in response to civil society pressure |

| Nepal | 2008 | Universal free health care up to district hospital level | Flagship social policy of incoming government |

| Ghana | 2008 | National Health Insurance coverage extended to all pregnant women | Leading up to a Presidential election |

| China | 2009 | Huge increase in public spending to increase service coverage and financial protection | Response to growing political unrest over inadequate coverage |

| Sierra Leone | 2010 | Free health care for pregnant women and children | Presidential initiative which was a major factor in recent elections |

| Georgia | 2012 | Extending health coverage to all citizens | Key component of new Government’s manifesto |

References

- Atun, R., The National Health Service: value for money, value for many. Lancet, 2015. 385(9972): p. 917-8.

- Etienne, C., A. Asamoa-Baah, and D.B. Evans, Health systems financing: The path to universal coverage. 2010: World Health Organization.

- Gottret, P.E. and G. Schieber, Health financing revisited: a practitioner’s guide. 2006: World Bank Publications.

- The World Bank. Indicators. 2015 [cited 2015 March 23]; Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator.

- Roberts, M., et al., Getting health reform right: a guide to improving performance and equity. 2008: Oxford university press.

- Jack, W. and M. Lewis, Health investments and economic growth: Macroeconomic evidence and microeconomic foundations. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series, Vol, 2009.

- Bloom, D. and G. Fink, The economic case for devoting public resources to health. Manson’s Tropical Diseases, 2013: p. 23-30.

- Atun, R. and S. Fitzpatrick, Advancing Economic Growth: Investing In Health. A summary, 2005.

- Grigoli, F. and J. Kapsoli, Waste not, want not: the efficiency of health expenditure in emerging and developing economies. 2013.

- Cutler, D.M., A.B. Rosen, and S. Vijan, The value of medical spending in the United States, 1960–2000. New England Journal of Medicine, 2006. 355(9): p. 920-927.

- Abiola, S.E., et al., Survey in Sub-Saharan Africa shows substantial support for government efforts to improve health services. Health affairs, 2011. 30(8): p. 1478-1487.

- Atun, R., et al., Universal health coverage in Turkey: enhancement of equity. The Lancet, 2013. 382(9886): p. 65-99.

- World Health Organization, The World health report: 2000: Health systems: improving performance. 2000.

- Hsiao, W.C., Abnormal economics in the health sector. Health policy, 1995. 32(1): p. 125-139.

- Shakarishvili, G., et al., Health systems strengthening: a common classification and framework for investment analysis. Health Policy and Planning, 2011. 26(4): p. 316-326.

- Jamison, D.T., et al., Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation. The Lancet, 2013. 382(9908): p. 1898-1955.

- Schwartländer, B., et al., Towards an improved investment approach for an effective response to HIV/AIDS. The Lancet, 2011. 377(9782): p. 2031-2041.

- Raviglione, M.C. and M.W. Uplekar, WHO’s new Stop TB Strategy. The Lancet, 2006. 367(9514): p. 952-955.

- Ki-Moon, B., Global strategy for women’s and children’s health. New York: United Nations, 2010.

- Roll Back Malaria, The global malaria action plan. Roll Back Malaria partnership, 2008.

- World Health Organization, Package of essential noncommunicable (PEN) disease interventions for primary health care in low-resource settings. 2010.

- Daniels, N., Accountability for reasonableness: Establishing a fair process for priority setting is easier than agreeing on principles. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 2000. 321(7272): p. 1300.

- Gruskin, S. and N. Daniels, Process is the point: justice and human rights: priority setting and fair deliberative process. American Journal of Public Health, 2008. 98(9): p. 1573.

- Maruthappu, M., et al., Government Health Care Spending and Child Mortality. Pediatrics, 2015: p. peds. 2014-1600.

- Anyanwu, J.C. and A.E. Erhijakpor, Health Expenditures and Health Outcomes in Africa*. African Development Review, 2009. 21(2): p. 400-433.

- Maruthappu, M., et al., Unemployment, government healthcare spending, and cerebrovascular mortality, worldwide 1981–2009: an ecological study. International Journal of Stroke, 2015.

- Moreno-Serra, R. and P.C. Smith, Does progress towards universal health coverage improve population health? The Lancet, 2012. 380(9845): p. 917-923.

- Hanvoravongchai, P., Health financing reform in Thailand: toward universal coverage under fiscal constraints. 2013.

- Limwattananon, S., et al., Why has the Universal Coverage Scheme in Thailand achieved a pro-poor public subsidy for health care? BMC Public Health, 2012. 12(Suppl 1): p. S6.

- Atun, R., et al., Health-system reform and universal health coverage in Latin America. The Lancet, 2014.

- Cutler, D.M. and M. McClellan, Productivity change in health care. American Economic Review, 2001: p. 281-286.

- Resch, S., et al., Economic returns to investment in AIDS treatment in low and middle income countries. PloS one, 2011. 6(10): p. e25310.

- Yates, R. and G. Humphreys, Arguing for universal health coverage.

- Atun, R. and S. Sparkes, Fixing a Broken Health System: Confronting Health System Challenges in Turkey. Harvard School of Public Health: Executive and Continuing Professional Education: Boston, MA.

- Couttolenc, B. and T. Dmytraczenko, Brazil’s primary care strategy. 2013.

- Paim, J., et al., The Brazilian health system: history, advances, and challenges. The Lancet, 2011. 377(9779): p. 1778-1797.

- Kepp, M., Upcoming election could rekindle health debate in Brazil. The Lancet, 2014. 384(9944): p. 651-652.

- Gomez, E.J. Why Dilma Rousseff was re-elected in Brazil. 2014 [cited 2015 April 1]; Available from: http://www.cnn.com/2014/10/27/opinion/gomez-rousseff-election-win/.

- Gershlick, B., A. Charlesworth, and E. Taylor, Public attitudes to the NHS: an analysis of responses to questions in the British Social Attitudes Survey. 2015, The Health Foundation: London.