Introduction

Policymakers in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are faced with numerous suggestions to boost economic growth and improve well-being. For instance, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals outline 169 targets to achieve by 2030 (United Nations, 2015). These goals include providing free, fair, and high-quality primary and secondary education for all children, ensuring universal access to affordable and reliable energy services, decreasing global maternal mortality rates to below 70 deaths per 100,000 live births, and making significant reductions in marine pollution.

Even though all these objectives have the potential to enhance economic growth and quality of life, policymakers in LMICs are faced with difficult decisions when it comes to choosing which goals to prioritize due to budget limitations. Therefore, it is crucial to determine which investment priorities are most effective in promoting long-term economic growth and development.

Data constraints frequently hinder in-depth analysis of the macroeconomic impacts of precise, detailed policies. Although randomized controlled trials are valuable for identifying effective policies at a local level, extrapolating these findings to a broader scope is challenging due to the limited scalability of many programs (Deaton & Cartwright, 2018). Nevertheless, policymakers can still derive value from broad recommendations on the strategies most likely to support economic growth.

Countries such as Mexico, Indonesia, and Tanzania offer valuable case studies on the effectiveness of human development investments. This paper examines how these nations have approached human capital development and evaluates the extent to which these efforts have contributed to economic growth. By analyzing specific policies and programs, we will assess the role of education, health, and social welfare initiatives in fostering economic growth and offer recommendations for policymakers navigating similar challenges.

Human Development Policies: A Country Comparison

In economic theory, poverty traps refer to self-perpetuating conditions that keep populations impoverished. Two approaches have emerged to help countries escape these traps: investments in physical capital (such as infrastructure) and investments in human capital (including education, health, and social welfare) (Bloom et al., 2021). The ideal approach is an economic development strategy that combines a carefully prioritized number of infrastructure and human capital investments with best prospect of generating sustainable growth.

Mexico: Progresa and Seguro Popular

In Mexico, the Progresa program launched in 1997 targeted low-income families with conditional cash transfers tied to school attendance and health check-ups. The program’s design was groundbreaking in its emphasis on human capital development, and it succeeded in improving school enrollment and enhancing health outcomes (Behrman 2009). Exposure to Mexico’s Progresa program during childhood resulted in an increase of 1.4 years in average educational attainment. Girls were 30 percentage points more likely, while boys were 18 percentage points more likely, to obtain some secondary schooling (Parker & Vogl, 2018). More than two decades later, Progresa (now Prospera) continues to serve as a model for similar programs worldwide. However, some criticisms point to the program’s limited impact on breaking intergenerational poverty, particularly in rural areas where infrastructure is still lacking.

Seguro Popular, introduced in 2003, was another significant policy aimed at expanding healthcare access to uninsured populations. The program successfully reduced out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures and improved health outcomes, particularly among marginalized groups (Frenk, Gómez-Dantés, & Knaul 2009). However, Seguro Popular faced challenges in terms of sustainability and cost-effectiveness, leading to its eventual replacement in 2020 with Instituto De Salud Para El Bienestar (INSABI) (Unger‐Saldaña et al., 2023). The shift from Seguro Popular to INSABI reflects ongoing struggles with maintaining sustainable, large-scale healthcare programs. Political changes and fluctuations in government priorities have had a direct impact on the long-term sustainability of these programs.

Indonesia: PKH and JKN

Indonesia experienced a decrease in fertility rates from 1982 to 1987 due to investments in family planning programs and economic development. Gertler & Molyneaux (1994) findings showed that 75% of the decline in fertility was attributed to the increase in contraceptive use, which was mainly influenced by advancements in education and economic opportunities for women.

Indonesia has also pursued policies focused on human capital. The Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH), initiated in 2007, aimed to improve educational and health outcomes for low-income families through conditional cash transfers. Like Progresa in Mexico, PKH resulted in better educational achievements and reduced malnutrition (Banerjee et al. 2017). However, Indonesia faces unique challenges such as its vast geographical disparities and the difficulty of delivering services across the country (Moh Idil Ghufron & Ahmad Ali Bustomi, 2022).

Moreover, Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional (JKN), launched in 2014, has increased healthcare utilization and alleviated the financial burden of health expenses, but concerns remain about the program’s financial sustainability (Agustina et al. 2019). Rising healthcare costs and inadequate funding models have prompted debates about the long-term viability of JKN. Indonesia’s geographic challenges—spread across thousands of islands—compound this issue, leading to unequal healthcare access between urban and rural populations.

Tanzania: PSSN and CHF

Tanzania’s approach to human development also highlights the importance of well-targeted social welfare programs. The Productive Social Safety Net (PSSN), launched in 2012, provides conditional cash transfers to poor households. This program has increased school attendance and improved health outcomes among children and pregnant women (World Bank 2019). Yet, similar to Indonesia, Tanzania faces challenges in ensuring that remote and underserved communities can benefit from the program. Issues of access and service delivery are compounded by inadequate infrastructure and limited governmental capacity in some regions.

The Community Health Fund (CHF), introduced in 2001, aimed to provide affordable healthcare to the rural and informal sector populations (Wang et al., 2018). While the CHF has enhanced health security in some areas, its coverage remains incomplete, and many citizens still struggle to access quality healthcare (Borghi et al. 2013). The program’s reliance on voluntary contributions has also led to low enrollment rates, raising concerns about the fund’s ability to provide universal coverage.

Empirical Evidence: Quantifying the Impact of Human Development

The relationship between human development and economic growth is well-studied in economic literature. David Bloom and colleagues (2021) identified three key domains—education, health, and reproductive health—as having the most substantial impact on economic growth in LMICs. Their research shows that improvements in these areas are strongly correlated with increased economic growth.

By conducting cross-country and panel data regressions, they determined that enhancements in these areas have a positive influence on future economic growth. The following key findings are crucial for policymakers in LMIC settings to consider:

- A decrease in the total fertility rate by one child corresponds to a 2-percentage point increase in annual GDP per capita growth in the short run and a 0.5 percentage point increase in the medium to long run (Bloom et al., 2021).

This dynamic is particularly relevant in countries like Indonesia, where high fertility rates have historically impeded economic growth. Policies promoting reproductive health and family planning have helped lower fertility rates, thus unlocking demographic dividends that contribute to economic growth.

- A 10 percent rise in life expectancy at birth corresponds to a 1 percentage point increase in GDP per capita growth in the short term and a 0.4 percentage point increase over the long term (Bloom et al., 2021).

Increasing life expectancy has a direct effect on economic performance. In Mexico, Indonesia, and Tanzania, healthcare reforms such as Seguro Popular, JKN, and the CHF have improved population health and life expectancy, thereby contributing to higher productivity and economic stability.

- A one-year increase in average years of schooling corresponds to a 0.7 percentage point increase in annual GDP per capita growth in the short term (Bloom et al., 2021).

The role of education in economic growth cannot be understated. In Mexico and Indonesia, conditional cash transfer programs like Progresa and PKH have contributed to higher school enrollment rates and reduced dropout rates, equipping future generations with the skills needed for productive employment. However, these programs also reveal limitations: while they improve access to education, they do not always address the underlying quality of education, which remains a concern, particularly in rural areas.

Economic Growth Through Human Development

Education plays a crucial role in driving long-term economic growth (Lutz et al., 2008). Individuals with higher levels of education tend to be more productive, earn higher incomes, and contribute more to overall economic output. However, in countries where fertility rates are high and families are large, there may be limited resources available to invest in each child’s education. This can lead to lower levels of education and lower earnings, which, in turn, can contribute to high fertility rates and large families in the next generation. This cycle can create a barrier to achieving sustained economic growth, as it hinders the transition to lower fertility rates and higher levels of education (Galor, 2011). This phenomenon, known as the fertility-induced poverty trap, is a significant challenge for low- and middle-income countries, preventing them from benefiting from the demographic dividend that comes with a shift in population age structure (Kotschy et al., 2020).

Moreover, unaffordable or low-quality education can hinder young people from developing the necessary job skills to improve their future earning potential. This cycle of limited education and low productivity can perpetuate poverty across generations, impede human capital accumulation, and restrict economic growth (Strulik et al., 2013).

In Mexico, Tanzania, and Indonesia, investments in education have led to better educational outcomes and higher productivity. Conditional cash transfer programs such as Progresa and PKH were instrumental in raising school enrollment rates and reducing dropout rates, ensuring that future generations possess the skills necessary to contribute to the workforce.

The Role of Health in Economic Development

Poor health conditions and high rates of infectious diseases can trap populations in poverty, as unhealthy individuals are less likely to invest in education or productivity-enhancing activities. In Tanzania, for instance, policies focused on improving maternal and child health have played a critical role in improving human capital. Tanzania’s Community Health Fund (CHF), which aims to provide affordable healthcare to rural and low-income populations, has led to significant improvements in population health, further contributing to the economic stability of the population (Borghi et al., 2013).

Individuals with poor health may have a lower life expectancy, making it less likely for them to benefit from investments in education (Cervellati & Sunde, 2013). As a result, private investments in education may not be seen as worthwhile, and public investments in education may not be fully utilized due to low demand. Poor health and its subsequent lack of access to education can limit a country’s potential for economic growth (Bloom et al., 2020).

Moreover, a lack of family planning in Indonesia have been associated with decreased economic stability. Kim et al. (2009) showed that the arrival of a newborn child in an Indonesian household led to a 20% decrease in household consumption per person over four years. As such, in countries like Indonesia, policies aimed at promoting reproductive health have contributed to reductions in total fertility rates, which in turn has contributed to economic growth.

Critical Analysis and Challenges

Across these countries, similar limitations arise. Progresa and PKH succeed in improving access to education and health services but struggle with the quality of services in rural areas. Yet, limited infrastructure, such as schools and healthcare centers, hinders the effectiveness of these programs.

In Mexico, INSABI, which replaced Seguro Popular (Unger‐Saldaña et al., 2023), has yet to prove whether it can maintain a sustainable healthcare system that reaches all populations. Meanwhile, Indonesia’s JKN faces increasing financial pressures, especially considering the informal sector unwillingness to pay for it (Muttaqien et al., 2021).

In all three countries, a lack of investment in infrastructure—whether physical or digital—limits the success of human capital programs. For instance, rural communities often lack electricity, internet access, and transportation, which are essential for both education and healthcare services.

Exploring Other Dimensions of Human Development

Beyond education, health, and reproductive health, several other dimensions significantly influence human development outcomes in LMICs:

- Gender Equality: Women’s access to education and healthcare is essential to driving down fertility rates and increasing economic participation. Programs that focus on maternal health and girls’ education in LMICs have shown success in improving gender equity, but challenges remain, particularly in rural areas (United Nations, 2020).

- Technology Access: Access to technology is becoming an increasingly important factor in both education and healthcare. The digital divide between urban and rural populations in LMICs can limit the potential benefits of human development programs. For example, telemedicine and online education initiatives can help bridge the gap (Dillip et al., 2024).

- Agustina, R., Dartanto, T., Sitompul, R., Susiloretni, K. A., Suparmi, Achadi, E. L., Taher, A., Wirawan, F., Sungkar, S., Sudarmono, P., Shankar, A. H., Thabrany, H., Agustina, R., Dartanto, T., Sitompul, R., Susiloretni, K. A., Suparmi, Achadi, E. L., Taher, A., & Wirawan, F. (2019). Universal health coverage in Indonesia: concept, progress, and challenges. The Lancet, 393(10166), 75–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31647-7

- Banerjee, A. V., Hanna, R., Kreindler, G. E., & Olken, B. A. (2017). Debunking the Stereotype of the Lazy Welfare Recipient: Evidence from Cash Transfer Programs. The World Bank Research Observer, 32(2), 155–184. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkx002

- Behrman, Jere R, et al. (2009). Schooling Impacts of Conditional Cash Transfers on Young Children: Evidence from Mexico. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 57(3), 439–477. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2832207/

- Bloom, D. E., Kuhn, M., & Prettner, K. (2020). The contribution of female health to economic development. The Economic Journal, 130(630), 1650–1677.

- Bloom, D. E., Khoury, A., Kufenko, V., & Prettner, K. (2021). Spurring economic growth through human development: research results and guidance for policymakers. Population and Development Review (2021).

- Borghi, J., Maluka, S., Kuwawenaruwa, A., Makawia, S., Tantau, J., Mtei, G., Ally, M., & Macha, J. (2013). Promoting universal financial protection: a case study of new management of community health insurance in Tanzania. Health Research Policy and Systems, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-11-21

- Cervellati, M., & Sunde, U. (2013). Life expectancy, schooling, and lifetime labor supply: Theory and evidence revisited. Econometrica, 81(5), 2055–2086.

- Dillip, A., Kahamba, G., Sambaiga, R., Shekalaghe, E., Ntuli Kapologwe, Kitali, E., James Tumaini Kengia, Tumaini Haonga, Nzilibili, S., Tanda, M., Haroun, Y., Hofmann, R., Litner, R., Riccardo Lampariello, Suleiman Kimatta, Sosthenes Ketende, James, J., Khadija Fumbwe, Mahmoud, F., & Lugumamu, O. (2024). Using digital technology as a platform to strengthen the continuum of care at community level for maternal, child and adolescent health in Tanzania: introducing the Afya-Tek program. BMC Health Services Research, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11302-7

- Drummond, P. (2015). Chapter 1. Overview. International Monetary Fund.

- Ekholuenetale, M., Barrow, A., Ekholuenetale, C. E., & Tudeme, G. (2020). Impact of stunting on early childhood cognitive development in Benin: evidence from Demographic and Health Survey. Egyptian Pediatric Association Gazette, 68(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-020-00043-x

- United Nations. (2015). The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations.

- United Nations. (2020). World Fertility and Family Planning 2020. UN Report.

- World Bank Group. (2019, September 16). Five Million Tanzanians to Benefit from Improved Safety Nets. World Bank.

Nutrition: Malnutrition continues to be a critical issue in LMICs, where large rural populations face food insecurity. Poor nutrition, especially in early childhood, can result in long-term health issues and impede cognitive development, directly affecting educational outcomes and economic productivity (Ekholuenetale et al., 2020).

Additionally, collaboration with international institutions has been used by Tanzania, Indonesia, and Mexico for a push to development in some contexts. Mexico’s entry into the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1994 led to economic and social reforms aligning with OECD standards, resulting in gradual improvements in human development indicators such as literacy rates and life expectancy (OECD, 1997). Indonesia’s ASEAN membership since 1967 facilitated regional cooperation, enhancing education, healthcare, and infrastructure, and driving human development (Lorraine Pe Symaco & Meng Yew Tee, 2019) Tanzania’s membership in the East African Community (EAC) since 2000 has promoted economic integration and social development (Drummond, 2015).

Conclusion

Investments in human capital—particularly in education, health, and reproductive health—are crucial for driving sustained economic growth in LMICs. The experiences of Mexico, Indonesia, and Tanzania demonstrate the potential of well-targeted human development policies to improve economic outcomes. However, these efforts must be complemented by critical investments in infrastructure, based on a country’s context, and must address national inequalities to achieve their full potential. Policymakers in LMICs should prioritize long-term strategies that integrate human development with infrastructure improvements, ensuring that gains in education and health translate into broad-based economic growth.

References

Appendix

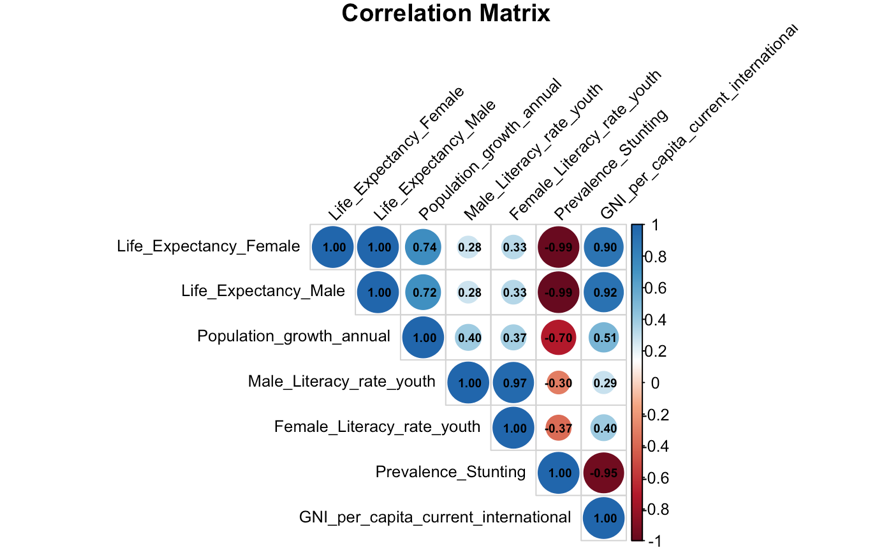

Graph 1: Tanzania’s Correlation Matrix

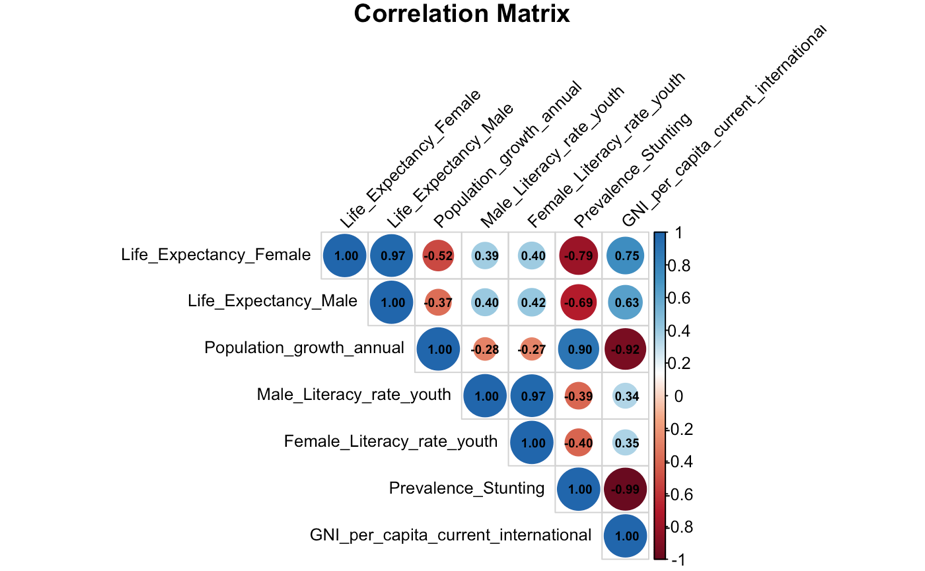

Graph 2: Mexico’s Correlation Matrix

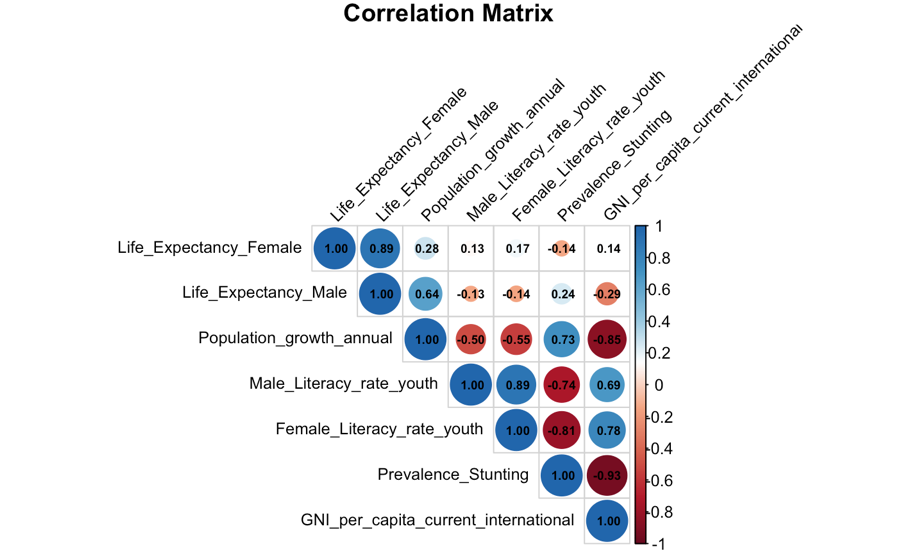

Graph 3: Indonesia’s Correlation Matrix